A century ago this month, conflict erupted in Derry with British state forces openly colluding with UVF gangs to quell the nationalist surge for independence. The following is an excerpt from ‘Violence and Nationalist Politics in Derry City, 1920-1923’ by Ronan Gallagher (2003).

By June 1920, violence was fierce, premeditated, and far from sudden.

After an attack on Catholics in the Prehen area of the Waterside on 16 June, the Derry Journal accused certain sections of the unionist population of wanton involvement in such incidents over the previous weeks: “Without interference on the part of the police, have night after night since the middle of May kept up a reign of terror in that part of the city, where apparently they are to have a free hand to carry on their murderous escapades.”

The presiding judge at the assizes, Judge Osbourne, was not amused by the lack of police intervention ‘when Fountain Street is ready to take a hand along with the police’. This admission that the police were standing idly by and not protecting the citizens was reinforced by a court case in July. This suggests that there was collusion in Derry between the military authorities, the RIC, and unionist squads based on the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

One writer of the period (a secretary in the publicity department of the Dail) alleged that there was a force called the ‘Civilian Guards’ operating in Derry under the auspices of Dublin Castle.

In a letter to the Journal, signed ‘Ratepayer’, another writer maintained he had “observed Unionists coming across the Bridge acting in a most provocative and blackguardly manner, with two policemen silently looking on.”

Collusion and apathy on the part of the authorities was about to prove fatal indeed.

As a result of the Prehen incident, notices were nailed to trees stating that “any Sinn Feiner found in Prehen or Prehen Wood after this date will be shot on sight, signed 14 June 1920”.

In an article which appeared in the Journal many years later, it was alleged that a Protestant gentleman sent word to Dublin that the Dorset Regiment had given weapons and ammunition to unionists.

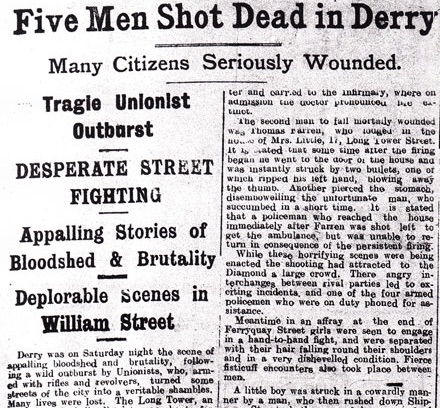

On Saturday 20 June, a scuffle developed at Bishop Street between rival factions before unionists unleashed a fusillade of shots down Albert Street and Fountain Street into Bishop Street and Longtower Street. One man, John O’Neill, was injured; but another, John McVeigh, was killed. John Farren died shortly afterwards having been hit by a ricochet bullet.

Another group of Orangemen came over from London Street before travelling down Bishop Street, where Edward Price was shot at the entrance of the Diamond Hotel. Liam Brady, a member of Fianna Eireann in Derry at the time, alleged that ‘an ex-army sergeant’ led this group.

Taking up positions in Butcher Street, they fired shots down Fahan Street, killing another man (Thomas McLaughlin) and injuring a woman who went to his aid. Also to die that night at the hands of unionist gunmen was James Doherty. Brady believed a drunken squabble had been the spark for the violence (an explanation some espoused in the Londonderry Standard). The Journal editorial of the same day stated: “That most desirable condition latterly has been departed from because of the recrudescence of violence and unchecked ‘loyalist’ terrorism.’”

Throughout Saturday night, street fighting occurred at many junctions where nationalist and unionist streets met, with unionist firepower overwhelming. By Sunday, the police and army had restored an uneasy calm to the flashpoints, but this did not stop the Journal on Monday accusing soldiers of standing idly by while unionist gunmen had a free hand. Indeed, Brady repeated this allegation: “No police or soldiers came to protect the nationalists although there was a battalion of the Dorset Regiment and hundreds of police in the city at the time.”

From the reporting in all the newspapers it is clear that those killed died as a result of firing from the city walls and Fountain area.

Even the Irish Independent noted: “It is undeniable that the police and military know the names of 50 or more Unionists who for some time past have kept up a reign of terror.”

In separate incidents, stores were looted and, in one instance, in William Street, a company of Irish Volunteers with hurley sticks was despatched to protect shops. Fire tenders were burned and groups of unionist and nationalist supporters exchanged shots in the Waterside, Carlisle Road, William Street and Bond Street.

As local newspapers disagreed on the origins of Saturday evening’s attacks in their Monday editions, workers on their way to the docks came under sporadic fire from across the river and snipers soon appeared on rooftops in the city to command strategic junctions:

“Snipers on Walker’s monument, the Protestant Cathedral, Bishop Street, the Orange Hall and the Masonic Hall in Magazine Street had a commanding view over most of the nationalist area and things were such that for a time the city was completely in the hands of the Orangemen”.

By Wednesday 23 June, another four men had died (William O’Kane, John Gallagher, Howard McKay and Joseph Plunkett), but the Irish Volunteers were now out in force. The Journal noted for the first time that Volunteers were carrying rifles and, on 25 June, they were referred to as the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

By Wednesday, machine guns were also in use and unionists had been driven from many of their key positions. The Journal again remarked: “the loss of Derry to the Unionist cause cannot be retrieved by the loss of so many Nationalist lives... Nationalists cannot be expected to ‘lie down’ under a raid any more than they would expect Unionists to do the same.”

Life in the city stood still, and few, other than the combatants, ventured out. There were gun battles throughout the city, including in the grounds of St Columb’s College, which was the scene of much bitter fighting. Referring to the original attack on the Long Tower, the Journal reiterated that it was “entirely premeditated and unprovoked”.

On Friday, extra troops arrived in the city and a Royal Navy destroyer laid anchor in the river Foyle. In the House of Commons, MPs such as Lord Cecil and Major O’Neill accused Bonar Law of not supplying the city with enough troops once the violence started. By the end of June there were over 1,500 soldiers and 150 RIC men in Derry, although prior to the fighting it was alleged in the house of commons that only 250 soldiers were on duty.

Denis Henry, Irish attorney-general, in a Dáil Eireann debate on Derry on Tuesday 22 June, said the explanation for so much trouble was that “it was an old city, full of rabbit-holes, from which men could shoot and retire at once out of sight. Derry differed from Dublin, where they shoot men in the back. In Derry there was an element of fight.”

With the arrival of troops, a stalemate developed. Liam Brady alleged that the IRA was planning a large-scale attack on Thursday 24 June when news came through that extra troops were being sent; he also accused the authorities of using the violence to gather intelligence on the strength of the IRA in the city. However, another IRA officer, Lieutenant M. Sherrin, although agreeing that this too was the reason for the abandonment of the attack, accused Republicans of cowardice when faced with the new contingent of British troops:

“Our force other than the IRA Company which occupied HQ could not be complimented on their conduct, after the first onslaught of the British they turned into a panicky mob. I was at the Headquarters at this time, and the terrible rush to the College; the discarding of rifles, ammunition etc., and hasty disappearance of the men was not edifying.”

But criticism of the government’s stance came from many quarters. Inaction, it was alleged, had cost the lives of many people. The city magistrates had requested extra troops on Monday 21 June and, not receiving a reply by Wednesday, the following was then sent to the chief secretary:

“City magistrates assembled today are greatly alarmed by no action having been taken by the government in response to previous telegram. They consider situation desperate and growing worse hourly. The food supply is running out, and gas supply almost exhausted. More lives lost last night. Magistrates request reply and assurance from government of immediate action to allay panic amongst citizens.”

Catholic families were driven from their homes in Carlisle Road, Abercorn Road, Harding Street and other unionist-dominated areas in the city before martial law was declared on Saturday 26 June. The Journal reported that Catholic homes continued to be raided whereas Protestant homes remained unscathed:

“Raids have not so far been made on the houses of Protestants though it is notorious that a Catholic was shot dead by a sniper concealed on the premises of a prominent Unionist in the city ... It is understood that Catholic members of the local constabulary force tendered their resignations as a protest against the conduct of certain soldiers who it is alleged permitted looting to go on and who actually shared the loot with Unionists.”

Its editorial continued: “The fires of sectarian passion in Derry have been set alight by a Unionist conspiracy in Belfast and London in order to maintain its squalid ascendancy in the North.”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)