Boris Johnson wants Ireland to abandon the backstop, the legal guarantee of maintaining an open border after Brexit, as his price for signing a deal with the European Union. But should Ireland give way and trust London? History suggests that could be a mistake. Here are some examples. By Naomi O’Leary (for Politico).

The Betrayal of Clannabuidhe

“Game of Thrones” has nothing on this.

Brian McPhelim O’Neill was a 16th century Gaelic lord who held lands that included Belfast and the surrounding territory. It was the time of the colonisation of Ulster — when land in Ireland’s northeast was forcibly taken over by English and Scottish settlers — that is the root of the island’s division today.

O’Neill sided with English forces to take on a rival, the powerful chieftain Shane O’Neill, and was knighted by the crown. But O’Neill soon found himself at war with the Earl of Essex, Walter Devereux, who had been granted permission to take over his lands by Queen Elizabeth I.

Queen Elizabeth I of England knights explorer Sir Francis Drake; engraved by F. Fraenkel from a drawing by John Gilbert | Hulton Archive via Getty Images

In the winter of 1574, the Earl of Essex used the pretence of a friendly banquet to wipe out O’Neill and his family, massacring those in attendance and taking O’Neill, his wife and brother captive, soon to be executed.

This breach of ancient hospitality rights has inspired poetry and was recorded in the medieval Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland as “sufficient cause of hatred and disgust of the English to the Irish.”

The Treaty of Limerick

This was the treaty that ended the 17th century Williamite War in Ireland, in which the Protestant Prince William of Orange defeated the Catholic King James II. The first article of the treaty guaranteed Catholics would maintain their rights and promised an Irish parliament would protect them.

However, this was swiftly followed by a series of laws barring Catholics from holding public office, owning firearms, serving in parliament, voting, owning a horse worth more than £5, and restricting their ability to inherit or own property. The stone on which it was reputedly signed is displayed prominently in the centre of Limerick, which takes its nickname “Treaty City” from the event.

The Act of Union

This was the act that merged Ireland fully into the United Kingdom in 1801 and dissolved its parliament, partly in response to a rebellion in 1798 that was inspired by the French Revolution and deeply rattled London.

“There are a lot of parallels to Brexit. The Act of Union was presented as this big panacea,” said Fin Dwyer, historian and presenter of the Irish History Podcast. Protection was promised for the Irish economy as it was integrated with the stronger British market. But protective measures were abandoned in the subsequent years and the Irish economy was devastated.

“The effect was dramatic. Within a couple of years people were saying that Dublin was a different city, that all the rich had fled to London,” Dwyer said.

The Act of Union also promised Catholic emancipation, by lifting the legal restrictions on Catholics and allowing them to hold political office. However, this was blocked by King George III once the act was signed. It took a massive political movement led by Daniel O’Connell and another 28 years before the restrictions began to be lifted.

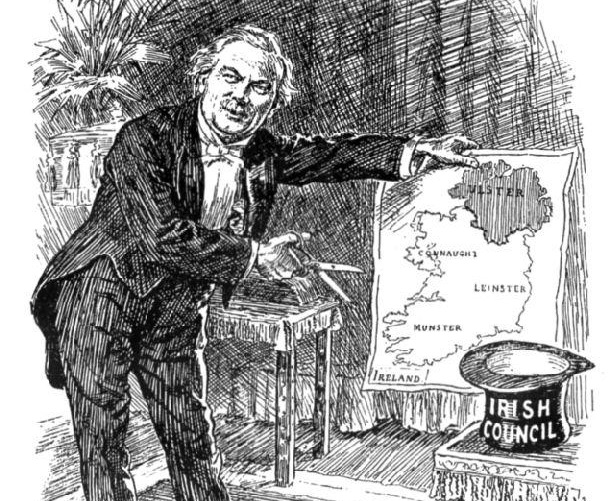

Home Rule

Bills to enact Home Rule — re-establishing a parliament in Dublin to give Ireland a measure of self-rule — were passed by the House of Commons but blocked by the House of Lords in 1893, 1912 and 1913. When the Lords’ objections were finally overcome in 1914 (after the removal of their veto), the bill’s enactment was delayed indefinitely by the outbreak of World War I.

The repeated delays contributed to the decision by nationalists to abandon the parliamentary route and mount a rebellion seeking full independence in 1916.

Those in favor of the union, particularly in the northeast of the island, felt betrayed by British support for Home Rule. Legislation on Home Rule fanned sectarian tensions in Belfast and was accompanied by deadly riots; some 500,000 signed the Ulster Covenant in 1912 refusing to recognise an Irish parliament, and unionists began to militarize to resist it.

Partition

Britain managed to betray both nationalists and unionists with partition.

The idea of resolving the Irish demand for self-rule with strong opposition in the north by dividing the island in two was initially introduced by British negotiators as a poison pill.

“The whole idea of throwing partition out there was to scupper Home Rule, to make a proposal so terrible that no one would ever accept it,” said Tim McMahon, associate professor of history at Marquette University in Milwaukee. “Both nationalists and unionists felt that they were being double-dealt.”

Nationalists were told that any partition would be temporary. Unionists were told that the aim was to keep the entire island within the U.K., and at worst there would be Home Rule for Dublin and special protection for the nine counties of Ulster. These promises were used to help recruit some 210,000 men to fight for Britain in World War I.

What ultimately happened was the partition of six counties in Ulster rather than nine, in order to ensure a stable unionist majority, while Britain agreed to an Irish Free State that went significantly further than Home Rule. For unionists, it was abandonment. For nationalists, partition and the requirement that members of the new Irish parliament would have to swear loyalty to the king was so bitter it provoked a civil war.

The division was particularly traumatic for those who found themselves on the wrong side of the border. Northern nationalists had believed they would soon live under all-island rule. Unionists in the counties of Monaghan, Cavan and Donegal suddenly found themselves living in the Catholic-dominated Irish Free State.

“You now have British politicians saying the Irish are bringing this border up to stop us from leaving Europe. As if the Irish put the border there,” said McMahon. “I would be leery of negotiating with such people just as a matter of principle.”

Putting Britain first

During World War II, Britain offered the Irish government of Éamon de Valera unification if it agreed to join the war effort. De Valera refused, as it would entail stationing British forces across the island, and he did not trust that the promise would be kept.

“I think this specific example is a really good one for pointing out why Ireland might be cautious about trusting the British government. Proposals like this are done purely in Britain’s self-interest. It’s about finding the particular carrot that will entice Ireland to do what they would like,” said McMahon.

“There were lots of suggestions after Brexit like ‘why don’t the Irish rejoin the Commonwealth?’ ‘Why don’t they just leave with us?’ That makes perfect sense to someone for whom Britain is No. 1. It makes no sense for someone with any sense of the Anglo-Irish relationship for hundreds of years, or the benefits that Ireland gets from its European Union membership now. It’s purely about British self-interest.”

History offers countless examples of policy set in London wreaking havoc in Ireland, not least in the Great Famine of the 1840s, which devastated the Irish population through starvation, emigration and disease.

“I think you’ve got several occasions where you have this disregard in British politics for Irish interest. I think the problem is that it’s reinforced today by the sense of the British government not acknowledging Irish history, and a complete lack of understanding in Britain about these issues,” said Dwyer.

“I do think it’s reflective of a conscious amnesia towards Britain’s imperial past, an intentional amnesia.”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)