This week 126 years ago – 31 July 1893 – the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) was founded. A look at the role it formed in the Easter Rising, by Brian Ó Conchubhair

When the Irish Volunteers and the Citizen Army seized key buildings in Dublin City centre on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, many, if not the majority, were believed to be members of Conradh na Gaeilge/The Gaelic League. When the self-declared Irish republic announced the Proclamation of Poblacht na hÉireann, six of the seven signatories were recognised members of Conradh na Gaeilge.

Of the 16 leaders to be executed, the majority were Gaelic League members and Irish speakers: Ceannt, Clarke, Mac Diarmada, MacDonagh, O’Hanrahan, P.H. Pearse, Willie Pearse, Plunkett, Casement, Heuston, Colbert, Daly and Kent. To further muddle the waters, Eoin MacNeill, in addition to being the co-founder of Conradh na Gaeilge/The Gaelic League in 1893 along with Douglas Hyde, was the president of the Irish Volunteers. One might be forgiven, therefore, for presuming that Conradh na Gaeilge/The Gaelic League was an ardent republican organisation, supportive of the IRB and military action rather than a non-political and non-sectarian association dedicated to the promotion of the Irish-language as a spoken language and the creation of a modern literature in Irish.

The Establishment of Conradh na Gaeilge/The Gaelic League

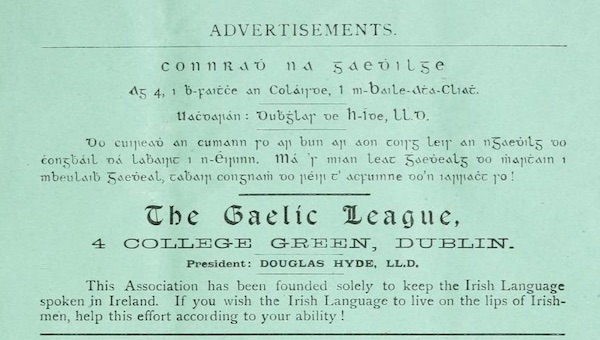

Douglas Hyde, following his late 1892 lecture on the need to de-anglicise the Irish nation and race, founded Conradh na Gaeilge/The Gaelic League in conjunction with Eoin MacNeill in 1893. With a focus on the vernacular form of language and modern literature, Conradh na Gaeilge/The Gaelic League distinguished itself from its rivals, The Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language, The Celtic Society and the Gaelic Union.

Initially a small Dublin-based group, it gradually spread – geographically and socially – across Ireland and beyond as new branches affiliated: Galway (24 January 1894), Cork (22 April 1894), Derry (1894), New Ross, Wexford (May 1894), Eyries, Cork (December 1894) and London (October 1896). By 1896, 43 branches had registered with the Dublin head-branch, eight of which were abroad.

The Rev. Peter C. Yorke’s controversial lecture on 6 September 1899, entitled ‘The Turning of the Tide’ marked a key moment in the League’s fortunes as membership in Dublin and its suburbs subsequently surged. By 1901 the capital boasted some 30 affiliated branches and two years later, in 1903, the League claimed 500 affiliated branches throughout the country. By 1904 Conradh na Gaeilge’s membership extended to some 50,000 members in 600 branches.

The rapid growth in members continued the following year with reports of 100,000 members in 900 affiliated branches amongst the Irish diaspora across the globe: Scotland (Glasgow), England (London, Liverpool, Manchester, Porstmouth, Southampton, Rugby, Birmingham, Leicester, Wigan, Oldham, Salford, Coventry, Bolton); Wales (Cardiff); Argentina (Piedad; Buenos Aires), United States of America (Chicago; New York; Holyoke, NY; Rhode Island), New Zealand (Miltown; Balcluttra), South Africa (Capetown; Kimberley). Increased membership impacted revenue: while 1895 showed a mere £43 in membership fees that sum rose to £2,000 by 1900. Such funding allowed the employment of full-time staff and community organisers (timirí) who travelled rural Ireland, often on bicycles or motorbikes, organising lectures, forming night classes, establishing branches, exhorting native and heritage speakers to the value of their linguistic inheritance. The Conradh’s curriculum of events matched the seasons: in winter they focused on classes where members, young and old, mastered the fundamentals of reading and writing – a valuable educational opportunity for many. Social interactions included excursions, céilí/céilithe, dancing, recitations, lectures, musical concerts, plays. Spring and summer months suited fairs, feiseanna, excursions, and exhibitions where the vernacular arts and cultures learned in the winter classes was displayed and exhibited. Irish-Week and the Oireachtas festival were high-points in the cultural calendar.

The Irish Volunteers: The Issue of Conradh na Gaeilge?

Eoin MacNeill, Gaelic League co-founder 20 years earlier, penned an article ‘The North Began’ in Conradh na Gaeilge’s weekly Irish-language newspaper An Claidheamh Soluis on 1 November 1913 in response to the Ulster Volunteers’ formation. On 25 November, at the Rotunda’s ice rink, some 7,000 people allegedly attended the Irish Volunteers’ first meeting, with 3,000 registering that night. MacNeill, as author of the article, was duly elected president but by his side stood several men associated with Conradh na Gaeilge – notably P.H. Pearse, The O’Rahilly, Thomas MacDonagh, Piaras Béaslaí – while in the background lurked the Irish Republican Brotherhood. At a meeting in Galway to establish the Volunteers in the western region, MacNeill was flanked by Pearse and Casement, all closely associated with Conradh na Gaeilge.

Yet the Volunteers, despite their title, Óglaigh na hÉireann, functioned and operated through the medium of English. The close overlap in membership between the two organisations proved detrimental to Conradh na Gaeilge’s activities, which slumped into a decline following the glory period of 1900-1910. Factions within the League considered its linguistic approach and policies too benign and called for more aggressive and confrontational gestures when promoting the language in the face of official intransience.

The Great War, Suspense and Suspension

When Great Britain entered World War I, the passing of the Suspensory Act (1914) ensured Home Rule’s postponement until the conflict’s conclusion. John Redmond, the Irish Parliamentary leader, urged the Volunteers to enlist in the army, and through their sacrifice ensure Home Rule for Ireland. This policy caused a split in the Volunteers with the majority following Redmond into the National Volunteers and the minority following MacNeill, Pearse, The O’Rahilly and Éamonn Ceannt into the Irish Volunteers.

As a self-declared non-political and non-sectarian organisation, Conradh na Gaeilge and its official newspaper, An Claidheamh Soluis, adopted no official stance on the war. But if the movement remained intact, its members disagreed and differed considerably. Hyde’s neutral stance allowed the Gaelic League to remain a home to Irish-speaking Redmonites, and Irish-speaking ‘Sinn Féiners’, Irish-speaking recruiters and Irish-speaking objectors. William Gibson (2nd Baron Ashbourne) and Tomás Ó Domhnaill M.P., both noted Gaelic Leaguers, encouraged young men to enlist, while Irish speakers who spoke at recruitment meetings were arrested and jailed for sedition. If An Claidheamh Soluis attempted to ignore commenting on the war, the Irish-language paper Ná Bac Leis (Ignore It) ridiculed Irish involvement in the war.

With Hyde’s shock resignation as President of Conradh na Gaeilge at the 1915 Ard Fheis in Dundalk, MacNeill stepped in temporarily to serve as President until Hyde would be coaxed back. He now, for all intents and purposes, controlled Conradh na Gaeilge and Óglaigh na hÉireann. The links between the two organisations seemed nearer than ever despite their divergent aims. Yet when the press reported the 1916 Rising, they titled it ‘the Sinn Féin Rebellion’ rather than ‘the Gaelic League rebellion’. MacNeill, as is well known, did not condone the rebellion, believing the Volunteers should wait for the war’s end and then seek the implementation of Home Rule as promised, but the IRB cared little for MacNeill once he had served his purpose of providing respectability and profile. By the time the 1916 Ard Fheis convened, most of Conradh na Gaeilge’s officials were in prison in England or Wales. While the links between the executed leaders and the Gaelic League bestowed no little honour on the organisation in the early years of the Free State and since, it spawned an enduring image of Conradh na Gaeilge less as a non-sectarian, non-political organisation but more one sympathetic to advanced republicanism. Such an understanding is far removed from that envisioned by Hyde.

Many, if not most, of those who fought on the nationalist side in Easter week were Gaelic Leaguers, but they were also affiliated to numerous other friendly societies: the Gaelic Athletic Association, Cumann na mBan. If there is a tendency to overplay the role of the Gaelic League in the 1916 Rising, it is impossible to underestimate its role in its leaders’ intellectual development and in introducing debates and discussions into early 20th-century Ireland that steeled the public for independence. It was Conradh na Gaeilge during the fin de siècle that provided the intellectual, linguistic and cultural rationale for political independence. But as has been well noted, revolutions are made not by hurleys and footballs but by ideas and Conradh na Gaeilge was the main conduit for radical ideas for reinventing and reenergising Irish society in the period building up to 1916.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)