Gerry Adams looks back at the historic peace initiative of August 1994 when the Provisional IRA declared a ceasefire. (For Léargas).

The IRA cessation is 25 years old this week. August 1994 was an intense month. I was involved, along with Martin McGuinness, and others in the Sinn Féin leadership, in intense, mostly private, efforts to persuade the SDLP Leader John Hume, the Irish Government and allies in Irish America to establish an alternative unarmed strategy to pursue republican and democratic objectives. Fr Alec Reid was central to this. And Fr Des.

The Sinn Féin aim was to open up the opportunity for a meaningful peace process that could bring about fundamental political and constitutional change. At the same time we were intent on advancing our republican objectives of ending partition and bringing about Irish Unity.

August 1994 was the month when it all began to come together. To be honest, neither Martin nor I really knew if we would succeed. We were attempting something unique and exceptional - to construct a series of agreements which together could persuade the IRA leadership that there existed an alternative to armed actions capable of achieving republican goals. The danger was that if we pulled everything together and the Army said NO then the process was over before it really started

Our discussions involved the Irish government; I was meeting John Hume; we were negotiating with the US administration through a variety of channels, and there was a delegation of Irish Americans – the Connolly House group – who were lobbying the Clinton administration to develop a new Irish agenda. We were also in contact with the British government though they were not part of the effort to develop an alternative.

At a briefing in early August with the IRA leadership Martin was able to tell it that the Irish government had provided written assurances that if there was a cessation there would be an immediate response on practical matters. Sinn Féin would be treated like any other political party. This would include a speedy meeting between the Taoiseach, Albert Reynolds, myself and John Hume.

Incidentally, after the cessation was declared and before that meeting Albert contacted me to say that Seamus Mallon had asked him to put our meeting back until he met with John Hume and Seamus. I dismissed this. The Taoiseach did not press it.

The Connolly House group had also passed back to us a document which set out a serious programme of work and commitment from them and Irish America. Entitled ‘Policy Statement by Irish American leaders’ it said that in the event of a ceasefire they would commit themselves to ‘the creation of a campaign in the United States dedicated to achieving’ a number of specified goals. Among these were an immediate end to all visa restrictions and the provision of unrestricted access for the Sinn Féin party leader.

The IRA leadership listened attentively to what we had to say. It agreed to meet again to receive an update from us. It was coming close to make your mind up time. Everyone at the meeting knew this. Some of the leadership were against a cessation. They had been very frank about that. It was going to be a close call.

I believed that we had to choreograph a series of statements, actually more public initiatives than statements, from John Hume, An Taoiseach Albert Reynolds, and the Connolly House group, which would signal the coming together of the different pieces of the jig-saw. We also needed a visa for Joe Cahill. It was one of the issues which the Army leadership had raised with us. Fundamentally it was a test to see if the Irish government was prepared to take on the British and if it could win such a political battle with the British within the US administration. It would also be an important indicator of how seriously the Clinton administration intended to take the issue of peace in Ireland.

The Connolly House Group returned to Ireland on August 25. The following Sunday John Hume and I met and issued another joint statement. Later that evening the Taoiseach, Albert Reynolds issued a statement in which he also expressed a belief that a historic opportunity was opening up.

Martin and I met the Army Council again. The meeting was inconclusive. People needed more time to consider all the issues. Joe’s visa became an even greater test. Then late on Monday night, August 29th, President Clinton cleared Joe’s visa.

Martin and I again travelled to meet the Army Council. A package had been agreed. It was now over to the IRA leadership. Everyone at the Army meeting was a little tense. Martin McGuinness spoke eloquently. So did others. For and against.

One of Martin’s great qualities was his sense of conviction and confidence. He could bring a strength to a debate which was very, very compelling. Even if you might not agree with him you knew he was going to deliver on any commitment he made or die trying. The struggle wasn’t ending we told them. They knew that of course.

In many ways, I said, the easy decision was for the IRA to continue to fight. That was the low risk option. The high-risk option was the one we were arguing for. It meant uncharted waters. It would involve compromises. It could mean risking – and losing – everything. But we could also be the generation who would win freedom. We could set in place a process which could create new conditions for a genuine and just peace and from there build a pathway and a strategy into a new all Ireland republic.

A formal proposal was then put to the meeting. The vote was for a cessation. It was not unanimous but those who voted against pledged their support to the new position. Unity, they said was essential.

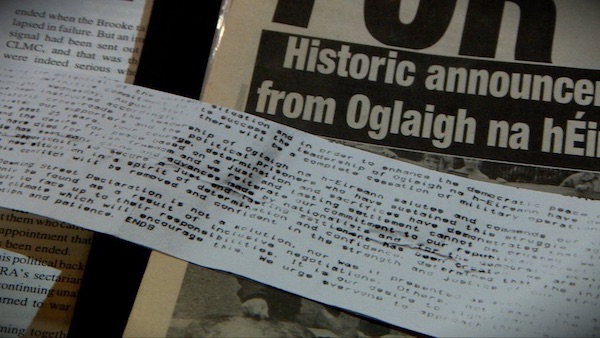

On Wednesday August 31st at noon the IRA declared its “complete cessation of military operations… We believe that an opportunity to create a just and lasting settlement has been created”.

The peace process and the dramatic changes that have taken place in the last 25 years owe much to the courageous decision by the Army Council and those other Volunteers who followed the path chosen by the IRA leadership.

A quarter of a century later much has changed. Ongoing political and demographic changes have increased the demand for more change. Political Unionism has lost its majority in the Assembly. Nationalism has rejected Westminster. There is a greater confidence and optimism. The demand for equality, for rights for all citizens is now part of our DNA. Support for a referendum on Irish Unity is growing. Nationalists and republicans will never again tolerate a second class status. Many within unionism have also come to accept the need for power-sharing and reconciliation and inclusiveness. And some are publicly speaking for the first time about the possibility of a new Ireland, a shared space which embraces the unity of all our people.

There are of course still challenges to be overcome. Brexit looms. The power sharing government is not functioning. There are still those within political unionism who see everything as a zero sum game in which any change – however innocuous – is a defeat. The British government is allied to the DUP and refusing to honour commitments made when the Good Friday Agreement was achieved. The Irish government and the southern political establishment could do much more to fulfill their obligations as co-guarantor of the Agreement. So, there is still much work to be done.

Looking back twenty five years ago to that period of our history and experience it is clear that dialogue, inclusive and based on equality, is central to any conflict resolution process – to any process of change. It is very telling that the then Leader of Unionism James Molyneaux described the cessation as ‘The most destabilising event since partition.’

Twenty five years later this assertion remains an insightful reminder of the worm at the heart of political unionism. That is the fear of positive political change. It is self-evident now that if it had been left to the Unionist leaders and the British Government there would have not been a cessation.

Thankfully they did not have a vote at the IRA’s Army Council meeting which took that decision.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)