By Kieran Allen (for Socialist Worker)

The most militant traditions of Irish workers are expressed in one word: Larkinism.

The mood of defiance and class solidarity associated with the name of James Larkin arose in the years before 1913. It then exploded again during the War of Independence when workers staged general strikes and occupations. It has left an abiding memory that lasts to this day. Even when the Gardai were fighting threatened pay cuts last year, they organised protests under the banner: 1913-Lockout-2013- Sell out.

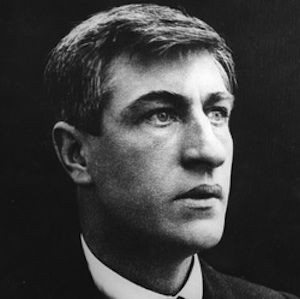

Jim Larkin was a revolutionary socialist, whose declared mission was the destruction of capitalism. Born of Irish parents, he first shot to fame in Liverpool in 1905 when he tried to establish a closed shop - a union only workplace. As a popular working class speaker and agitator, he had no rival. He was appointed a union organiser for the National Union of Dock Labourers by an ex-Fenian, James Sexton.

His first organising mission was in Belfast in 1907, where he pulled together one of the most magnificent examples of working class solidarity. A mass meeting of over 10,000 Catholic and Protestant workers was held in solidarity with a dockers’ and carters’ strike. Even the police mutinied, with many joining the strike. Tragically, however, the strike was sold out by Sexton who had become a typical union bureaucrat.

The ITGWU

The lesson was not lost on Larkin and in 1909 he set up a new union, the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. This union was to be built on a totally new philosophy and it was never about just one man, as Larkin himself argued:

‘Don’t bother about cheering Larkin - he is but one of yourselves. It is you that want the cheers and it is you that deserve them. It is you and the class you come from - the downtrodden class- that should get the cheers. I don’t recognise myself- a mean soul like myself in a mean body - as being the movement’.

Larkinism was, in fact, the Irish version of revolutionary syndicalism -a movement that swept the US, France, Britain and other countries and was indirectly inspired by the 1905 Russian Revolution. Instead of waiting for parliamentary representatives to deliver socialism to the working class from above, it argued that workers should win socialism through their own actions.

This anti-capitalist message guided the tactics of the ITGWU. James Connolly put the matter succinctly when he stated that the union believed that ‘No consideration of any contract with a section of the capitalist class absolved any of us from taking instant action to protect other sections when (they) were in danger from the capitalist enemy.’

In other words, the union was not a professional industrial relations service that sought compromises and friendly relations with employers - its strategy was based on the reality of class war. The union saw agreements with employers as temporary arrangements that could be broken if there was a need for solidarity. From this outlook sprung the doctrine of the sympathetic strike.

Arnold Wright was one of the main propagandists for the Dublin employers. But he was accurate when he recognised that Larkinism was not about ‘an ordinary English type of union’. It was, he argued, ‘a revolutionary rising’, intent on ‘the destruction of Society quite as much as the betterment of the wage conditions of the workers’.

The Irish Worker

In 1911, the Irish Transport and General Workers Union launched its own weekly paper the, Irish Worker, edited by Larkin. It had an average circulation of 20,000 a week, rising sometimes to 70,000. The historian Desmond Greaves claimed that ‘it was read or discussed by the entire working class of the city.’

It was a magnificent example of working class journalism. It turned the world upside down and made the rich and powerful the object of working class contempt. It called employers like William Martin Murphy, for example, ‘the most foul and vicious blackguard that ever polluted the country’. Its mocking, sneering tone was designed to raise workers from a mood of subordination and defeat to one of pride in their own class and confidence to take on their enemy.

‘The Irish working class are begging to awaken’ it proclaimed, ‘They are coming to realise the truth of the saying ‘He who would be free, himself must strike the blow’.

It has sometimes been argued that syndicalism avoided politics - but this was by no means that case, with the Irish Worker. It set out to boldly decolonise the Irish mindset and became the strongest organ of militant anti-imperialism. It openly promoted the republican ideals of Fintan Lawlor and Wolfe Tone.

It took up arguments with the Catholic Church when it attacked socialist politics but still suggested that, ‘There is no antagonism between the cross and socialism. A man can pray to Jesus the Carpenter and be a better socialist for it. Rightly understood, there is no conflict between the vision of Marx and the vision of Christ’.

One Big Union

Larkin’s strategy was to build ‘One Big Union’ that would eventually be organised in every workplace. Once that had been achieved, the working class would declare a general strike. This would constitute the final ‘lock-out’ of the employers and workers would then take over society.

The strategy, unfortunately, had two weaknesses. It assumed that workers could build up their economic strength under capitalism - much like capitalists had built theirs under feudalism. However, as 1913 showed, defeats can be imposed by employers and so the One Big Union could never accumulate more economic strength that the capitalists.

Second, Larkinism advocated revolutionary socialism but neither Larkin nor Connolly focused on building a revolutionary party. They tended to see political developments as only ‘an echo’ of the industrial battle and played down the need for a party that had a coherent view of the world. At the height of the 1913 battle, they made no effort to recruit workers to a socialist party.

While the struggle was going up, this did not seem to matter much. But defeats breed political confusion and by the time the workers movement began to revive after 1918, that confusion was rife. Many workers were looking to Sinn Fein and even Connolly’s own daughter, Nora, was talking as if Arthur Griffith was ‘a God-given saint’ - even though he had opposed workers in 1913.

The Russian Revolution

Larkin recognised some of these problems when he became an enthusiastic supporter of the Russian Revolution. In August 1919, he helped to found the Communist Labour Party in America. But he was caught up in a vicious crackdown against the American left and sentenced to five years in Sing Sing prison for ‘criminal anarchy’.

He was released in 1923 and returned to Ireland as a convinced supporter of the Bolshevik revolution. The following year, for example, he led 6,000 mourners through the streets of Dublin after Lenin’s death.

Larkin was never successful in building a revolutionary socialist party and later he retreated from this position to eventually join the Labour Party.

But during the commemoration of the 1913 lockout, there is a need to uncover its hidden history to discover how revolutionary socialism - in its Larkinite form- won the allegiance of so many Irish workers and left us a vital marker for the future.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)