On March 17, 1858, 152 years ago this week, James Stephens founded the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in Dublin at the same time as John O’Mahoney was founding the American branch of the revolutionary group.

O’Mahoney gave the organization the better-known name Fenians, in honor of the Fianna, the soldiers led by Fionn Mac Cuchail, the heroic warrior of Irish legend. The Fenians were the first truly worldwide revolutionary organization, with branches in France, England, Ireland, Australia, Canada and the United States. The group raised millions of dollars among Irish exiles in the U.S. to support efforts at gaining Ireland her independence, setting a precedent that continues. Though the founders of the Fenians never saw their goal come to fruition, Ireland’s freedom was built on the foundation they laid down.

The IRB played an important role in the history of Ireland. It was the chief group advocating armed revolt during the campaign for Ireland’s independence from England during the latter half of the nineteenth century, and organised an abortive revolt in 1867.

Although the IRB co-operated with Charles Stewart Parnell’s Irish Parliamentary Party (which opposed armed action) in the 1870s and 1880s during the Land War, it also was associated with a dynamite campaign in English cities in the 1880s. Its members often referred to themselves as “Fenians”.

In ths US, the Fenian Brotherhood (later Clan na Gael) would organize several raids into British Canada from 1866 to 1871 in an effort aimed at exchanging control of Canada for Ireland’s freedom.

Origins

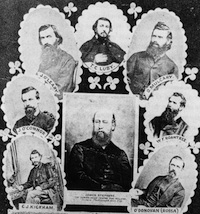

James Stephens, one of the “Men of 1848,” (a participant in the 1848 revolt) had established himself in Paris, and was in correspondence with O’Mahony in the United States and other radical nationalists at home and abroad. A club called the Phoenix National and Literary Society, with Jeremiah Donovan (afterwards known as O’Donovan Rossa) among its more prominent members, had recently been formed at Skibbereen. Stephens visited it in May 1858 and made it the centre of his preparations for armed rebellion.

The object of Stephens, O’Mahony, and other leaders of the movement was to form a league of Irishmen in all parts of the world against British rule in Ireland. The organization was modelled on that of the Jacobins of the French Revolution; they even formed a “Committee of Public Safety” in Paris, with a number of subsidiary committees and affiliated clubs. The Fenians were soon found in Australia, South America, Canada, and above all in the United States, as well as in the large cities of Great Britain such as London, Manchester, and Glasgow. The Fenians had more trouble gaining the support of the tenant-farmers or agricultural labourers in Ireland, because of their fears of British government reprisals. The early movement was also denounced by the Catholic Church, as indeed were all Irish separatist movements that advocated the use of force. One Irish bishop famously declared that “Hell is not hot enough, nor eternity long enough” for the Fenians.

It would be a few years after its foundation before the IRB made much headway. The Phoenix Club conspiracy in County Kerry had been betrayed by an informer and was crushed by the government. Some twenty ringleaders were put on trial, including Donovan, and when they pleaded guilty were, with a single exception, treated with leniency.

1867 Revolt and Land agitation

About the same time the Irish People, a revolutionary journal, was started in Dublin by Stephens, and for two years advocated armed rebellion and appealed for aid to Irishmen who had received military training and experience in the American Civil War. At the close of that war in 1865, numbers of Irish who had borne arms flocked to Ireland, and the plans for a rising were worked on. The government, well served as usual by informers, now took action. In September 1865 the Irish People was suppressed, and several of the more prominent Fenians were sentenced to terms of penal servitude; Stephens, through the connivance of a prison warder, escaped to France. The Habeas Corpus Act was suspended in the beginning of 1866, and a considerable number of persons were arrested. The failed revolt the following year proved a serious setback to the IRB’s hopes, with numerous arrests in both Ireland and Britain.

In the years following the failed revolt, leaders of the IRB carried out their own foreign policy, and courted support from ambassadors of nations they perceived as enemies of England. When the chances of war with England were fading, IRB looked for allies among other Irish national groups, and on the cusp of the 1870aO”1880s, their attempts at coalition building were successful. From amongst the many Irish nationalist organisations, a coalition was formed among the IRB and sections of the Irish Land League. In 1882, a breakaway IRB faction calling themselves the Irish National Invincibles assassinated the British Chief Secretary for Ireland Lord Frederick Cavendish and his secretary (see Phoenix Park Murders).

In March 1883 the London Metropolitan Police’s Special Irish Branch was formed, initially as a small section of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), to monitor IRB activities. Subsequently, the term ‘Irish Branch’ was replaced by the Special Branch title, as over time it took on responsibility for countering a wider range of revolutionary and anarchist activity.

Nineteenth-century Fenianism was among the most important movements in modern Irish history. Its radicalism influenced later leaders like Patrick Pearse and A 0/00amon de Valera and the IRB was well placed in the subsequent independence movement with Michael Collins at the helm. However, though influential in radical nationalism, the early IRB never gained widespread popular support and its attempts to stage rebellions in Ireland failed dismally. Its impact was through the ideas it developed among later Irish nationalists.

Later History

Revitalised from about 1910, the IRB was the chief organising force behind the Easter Rising of 1916, under the leadership of such men as Tom Clarke, Sean MacDermott and Patrick Pearse. The IRB infiltrated the Irish Volunteers, and commandeered them to act as the military wing of the republican movement, against the wishes of the Volunteers’ leadership. It was also a major influence during the 1919aO”21 Irish War of Independence. Its president since the summer of 1919 was Michael Collins, who was also a chief organising force behind the Irish Republican Army. Due to Collins’ leadership, the IRB accepted the Anglo-Irish Treaty agreed by Collins with the British government as compatible with its aims and dissolved itself. In fact, Collins used the IRB in 1922 as a vehicle for getting the Treaty accepted by IRA officers. This was somewhat strange as the IRB had up to this point been the most extreme Irish republican organisation. Anti-Treaty republicans like Ernie O’Malley, who fought a civil war against the Treaty, saw the IRB at this time as being used to undermine the Irish Republic.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)