A brief autobiography by former political prisoner and author Tim Brannigan for the BBC radio show ‘It’s My Story: Where Are You Really From?’

I was born on 10 May, 1966. I died, apparently, the very same day. Well, that’s what everyone was told. The first year of my life was treated as a death in the family.

“Stillborn,” said the hospital staff and with that brutal, clinical fabrication I was taken off to a “home” in east Belfast, while my mum was left to weave an elaborate, tearful lie to her family and friends.

My father was a medical student in Belfast. While he was from Ghana, my mum and her Belfast family were white. The baby was black, and still is.

My story begins in 1965 when Mum started to emerge from the grind of domesticity and the frustrations of an imperfect marriage to find a social life of her own.

At a dance in Belfast, she took exception to some of the girls in her company referring to a “very handsome” black man as a “nigger”.

She stuck two fingers up to the bigots by asking him to dance during “ladies’ choice”. His name was Michael.

“I never thought someone like him, with his background and education and breeding, would be interested in someone like me,” she told me years later. Soon after they met, she was pregnant.

She agonised over what to do all through her pregnancy and was petrified of the reaction of her devoutly Catholic and much-respected parents, and so the family was told I had died in the delivery room.

The lengthy official registration ledger at the home, which I saw in 2006, had only one notable detail about my arrival: “Not for adoption” was Mum’s instruction.

A year later she took me home, thereby saving me from a life of institutional care as black babies were never chosen for adoption.

All of her family and friends believed I would make up for the child Mum had “lost”.

My father, meanwhile, had retreated back to his own wife and family in south Belfast and we never had any contact.

He eventually left Northern Ireland in the early years of the Troubles but all through my life and particularly in the year before her death in 2004, Mum urged me to find him.

I grew up in a republican family and, even when little, I was subjected to racist hostility and abuse from the endless British army patrols.

One of my earliest memories of the “Brits” was a foot patrol of Scottish soldiers shouting terrible racist insults at me with considerable ferocity as I stood in the back garden of my home.

Given that I was about six years old at the time, it was nothing short of child abuse.

A woman soldier with blonde hair shouted at them to “stop it”. She made an apologetic gesture to me as her patrol headed on their way. Her decency made me smile then and still does.

In an almost exclusively white city, the only black people I ever saw were nervous-looking black soldiers.

I too was nervous, as their brothers-in-arms used to make racist jokes the second they saw me - the “weak link” in a hostile community.

Irish people, using the same “weak link” rationale, called the black soldiers “nigger” or “coon”.

Even my Irish accent made me a target for the Brits. Often they would ask me my name or simply just order me to “say something” to confirm that I had an Irish accent.

If I spoke, it became a source of great hilarity for the Brits and considerable humiliation for me.

They physically assaulted me on numerous occasions when I was a teenager and they called a girl I was seeing a “nigger lover”.

For her part, Mum scrupulously made sure I did nothing to confirm the prevalent racist stereotypes.

When I was three years old, she trailed me into the house by the arm after catching me urinating by our garden gate in case neighbours assumed that black people knew no better.

As a teenager she stopped me going back to work in a club because they had me mopping the men’s toilets, exposing me to more “jokes” from the drunken clubbers.

I decided to study politics at Liverpool Polytechnic. It would expose me to a city with a large black population and I could enjoy the electrifying sight of John Barnes, Liverpool’s first black signing, dazzle the Kop.

In reality Liverpool, like Belfast, was a segregated city, with black people almost invisible. They rarely ventured beyond the Toxteth area.

I, meanwhile, began to emphasise my Irishness as the war at home went through one of its more surreally violent phases beginning with the IRA being undone by the SAS in Gibraltar.

I graduated in July 1990 and returned to Belfast for a break.

While I was home alone one evening, two IRA men knocked on the door. They were looking to leave some weapons on our property overnight before moving them on. An informer tipped off the police and I ended up in jail.

Blacks have not played a major part in the history of the republican struggle. While serving a seven-year sentence for possession of guns and explosives, I was the only black man in the H-Blocks among several hundred IRA men.

Racism was hardly an issue as it was the most left-wing environment I’ve ever been in - and I studied at Liverpool Polytechnic.

My release came a year into the IRA ceasefire in 1994 and I decided to capitalise on the transformed atmosphere by aiming for a career in the media. I didn’t expect to get very far.

I enrolled in a basic training course and was stunned to find myself reporting local news for GMTV’s Northern Ireland bureau only months after my release.

My first story was about the Belfast reaction to the IRA bomb at Canary Wharf. A few years later, a stint at a local newspaper earned me a Best New Journalist of the Year award.

My success meant Mum was keener than ever for me to find my father, although I was still reluctant as I was proud of my Irish family and identity. Mum died in 2004 after a year-long battle with cancer.

By 2006, a chance to realise her last wish became too good to ignore. Working with BBC Radio 4, I began to search for my father.

Mum’s foresight in the 1960s paid off for me. She gave me my father’s surname as my middle name and she somehow got his name onto my birth certificate, even though in those days it was illegal to have the father’s name included unless the parents were married.

We met in Ghana in July and got on famously under African skies. Further meetings are likely. I wish Mum was around to hear about it, but I’m telling her now, I suppose.

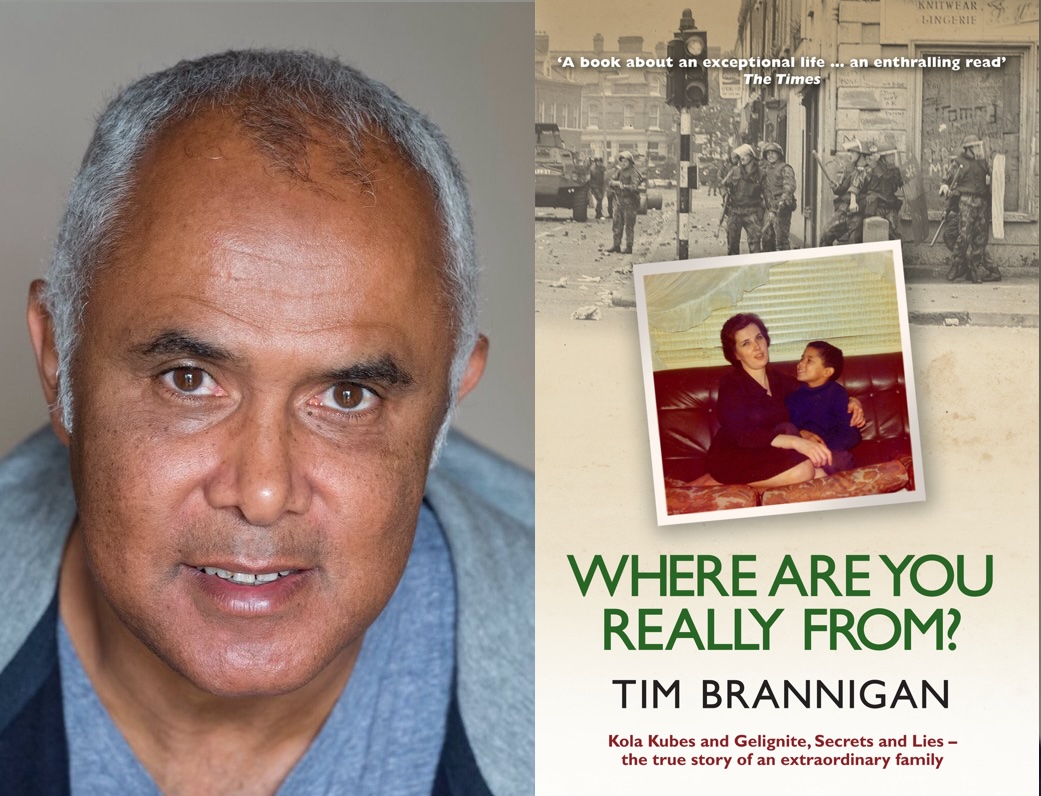

* Tim Brannigan is the author of Where Are You Really From?: Kola Kubes and Gelignite, Secrets and Lies – The True Story of an Extraordinary Family.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)