How the ‘third man’ on the Boundary Commission 100 years ago helped secure the border for unionism, by Cormac Moore (for the Irish News)

One hundred years ago, in October 1924, the third and final representative to the Irish Boundary Commission, Joseph R Fisher, its Northern Ireland representative, was appointed by the British government, paving the way for the body to finally convene, which it did for the first time on November 6 in London.

His appointment was crucial as the Boundary Commission had been in serious doubt for much of 1924.

Like the Free State representative, Eoin MacNeill, Fisher did not play an active role in Boundary Commission proceedings, which were dominated by the chairman Justice Richard Feetham.

Despite giving a vow of secrecy not to disclose Boundary Commission matters, Fisher broke the promise immediately and recurrently from thereon, providing Ulster unionists with inside information throughout its year-long lifespan.

Joseph Robert Fisher was born in Raffrey, Co Down in 1855, where his father was the Presbyterian minister. He studied at Queen’s College before being called to the English Bar.

He was more interested in journalism and political history than the law. He became editor and managing director of the Northern Whig in 1901, staying in the post until 1913, a time of great upheaval in Ulster.

According to the obituary for Fisher in the Northern Whig following his death in 1939, “in opposing to the death Dublin rule for the north, Mr. Fisher did a man’s part with both voice and pen”.

Fisher was an early advocate of partition as an end instead of as a means to end Home Rule for Ireland. He was also an historian who wrote books such as Finland and the Tsars and The End of the Irish Parliament.

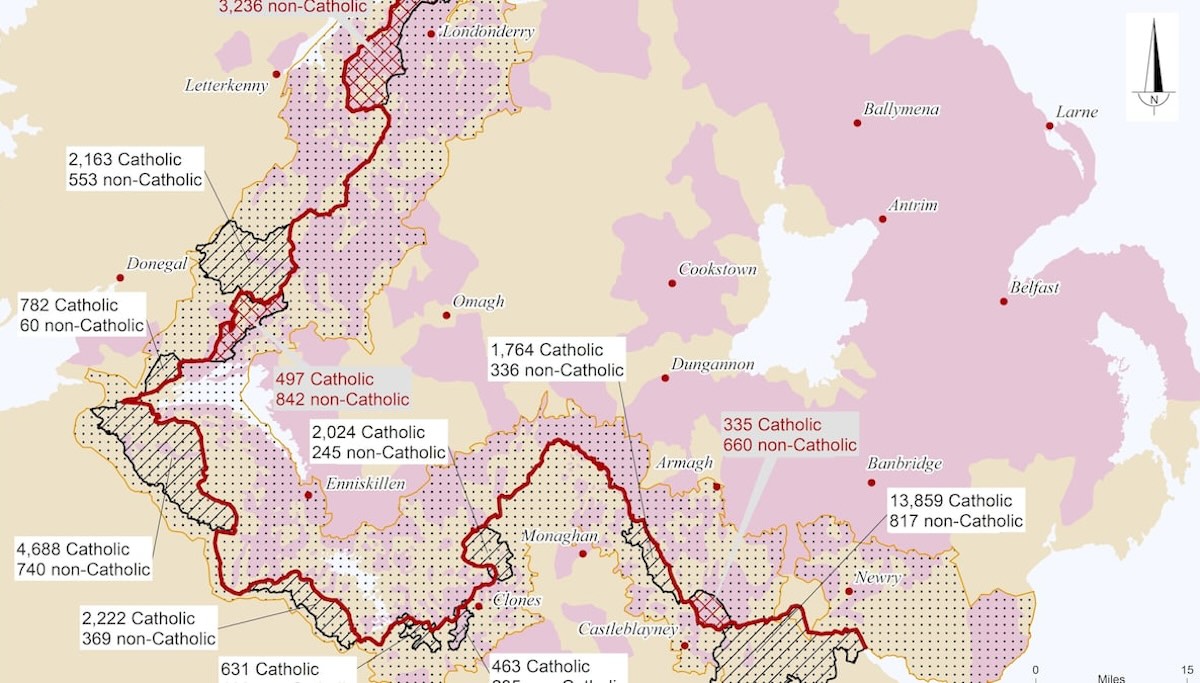

Fisher remained close with James Craig and Edward Carson after his time at the Northern Whig. Writing to Craig in late 1922, he thought Northern Ireland could benefit from rectification of the border. He stated: “Ulster can never be complete without Donegal. Donegal belongs to Derry, and Derry to Donegal”.

He also wanted “North Monaghan in Ulster and south Armagh out”. The border, he envisaged, “would take in a fair share of the people we want and leave out those we don’t want”.

There was little doubt that Fisher would do what was right for Ulster unionists’ interests. It seems, though, he was not the first choice as the Northern Ireland representative. With the northern government refusing to recognise the Boundary Commission and, therefore, make an appointment, legislation in both Westminster and the Oireachtas allowed the British government to make the appointment instead.

Even though Craig had caused so much trouble by not nominating a commissioner publicly, it appears that the British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald still allowed him to nominate a commissioner privately.

The first person approached was Craig’s predecessor as Ulster Unionist leader, Edward Carson. In late September 1924, according to Lady Ruby Carson, when approached Edward “felt he had to say he would but I am not sure he feels very happy about it”.

Craig asked his northern cabinet colleagues “is it not better to get a man of such outstanding ability on the commission to look after Ulster’s interests”. Others in the cabinet saw dangers in Carson being appointed, with Lord Londonderry saying “it will look like a put-up job”. John M Andrews saw in the “dangerous question of Newry a very difficult one for Carson especially if we get Inishowen”. Craig declared that “Carson would not give up Newry”.

Carson subsequently turned down the appointment, after being told by Craig that “it would cause a ‘crisis’ in the six counties”. Joseph R Fisher was appointed by MacDonald instead, after being advised by Craig.

Almost immediately after agreeing to keep Boundary Commission matters confidential at its first meeting, Fisher was writing to the editor of the Northern Whig, Robert Lynn, revealing details of its work.

Fisher proposed to the secretary of the northern cabinet, Wilfrid Spender, the setting up of a “back channel of communication” that the northern government “would need to counter Free State claims”. He subsequently wrote many letters to Florence Reid (née Stiebel), wife of Westminster Ulster Unionist MP David Reid, informing her of the commission proceedings, which undoubtedly were filtered through the party ranks.

In one such letter in July 1925, he told her: “All is going smoothly, and the more extravagant claims have been practically wiped out. It will now be a matter of border townlands for the most part, and no great mischief will be done.”

Ulster Unionist politicians made several statements in the summer of 1925, boasting that the Boundary Commission would deliver for them. The veil of paranoia and uncertainty of four years seemed to have lifted off the unionist psyche by then, undoubtedly aided by the leaks of Fisher.

Once the three commissioners agreed a preliminary award on October 17 1925, a day later David Reid informed Craig: “Newry and the whole of Co Down is safe… We lose no town of any importance.” Fisher wrote to Carson on the same day, saying, “your handiwork will survive”.

The Morning Post forecast of November 7, recommending small changes to the border on either side, which sent shockwaves throughout nationalist Ireland and led to the Boundary Commission collapsing, was so close to the actual award that most people have assumed that Fisher leaked it to the newspaper, something he never admitted himself.

Culpability still probably lies with Fisher, as it is likely the award details were leaked by someone who had received the details from Fisher either directly or indirectly.

MacNeill subsequently remarked that throughout the Boundary Commission sittings, Fisher was very “impassive and had left all to Feetham”, something he could have easily said about himself. There was no need for Fisher to be assertive, though, with Feetham sharing his views on rectifying the border.

Fisher’s persistent breaching of the confidentiality agreement was unquestionably valuable to Ulster unionists during the Boundary Commission sittings. In statements and interviews, nationalists tended to focus on the “wishes of the inhabitants”, even though the 1911 census returns and details on elections were readily available.

Fisher undoubtedly steered unionist representations towards issues he believed were important to Feetham, such as economic factors, and his interventions may have been decisive in places like Newry being recommended to be kept in the north.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)