An account of the largest republican hunger strike in Irish history at the end of the Civil War.

On 24 May 1923, Frank Aiken, the Chief of Staff of the IRA, had ordered his men to dump arms but, though the Civil War was officially over, arrests by the Free State continued unabated. By October 1923 tension was at an all-time high in the prisons and camps because of prison conditions and with no release in sight.

On 13 October 1923, Michael Kilroy, O/C of the IRA prisoners in Mountjoy, announced a mass strike by 300 prisoners, and it soon spread to other jails. Within days 7000 republicans were on hunger strike.

The figures given by Sinn Féin at the time were : Mountjoy Jail: 462; Cork Jail: 70; Kilkenny Jail: 350; Dundalk Jail: 200; Gormanstown Camp: 711; Newbridge Camp: 1,700; Tintown: 123; Curragh Camp: 3,390; Harepark Camp: 100; North Dublin Union: 50 women.

On that same day, the prisoners in Kilmainham Gaol went on strike, and O’Malley wrote eloquently of it in his book on the Civil War, The Singing Flame. He noted that “practically all volunteered; some were exempted, including myself, but I refused this concession”.

Previously, the Free State Government had passed a motion outlawing the release of prisoners on hunger strike. Dan Downey had died in the Curragh on 10 June, and Joseph Witty, only 19 years old, also died in the Curragh on 2 September.

However, because of the large numbers of Republicans on strike, at the end of October the Government sent a delegation to Newbridge Camp to speak with IRA leaders there.

It soon became apparent that they were not there to negotiate the strikers’ demands, but rather to give the prisoners the Government’s message: “we are not going to force feed you, but if you die we won’t waste coffins on you; you will be put in orange boxes and you will be buried in unconsecrated ground”.

O’Malley wrote: “Any action was good, it seemed, and everyone was more cheerful when the hunger strike began.

We listened to the tales of men who had undergoneprevious strikes and we, who were novices, wondered what it would be like.

We laughed and talked, but in the privacy of our cells, some, like myself, must have thought what fools we were, and have doubted our tenacity and strength of will.

I looked into the future of hunger and I quailed”.

All negotiations to curtail the strike were abandoned and the strike went forward. Poorly planned, within weeks many were going off strike, but by the end of October, there were still 5,000 on strike.

O’Malley did not know what effect the strike would have, but he felt he could not “let the side down”.

“Hunger striking was an unknown quantity for me. I did not approve of it. I was frankly afraid, but I could not see boys of sixteen and eighteen take their chance whilst I could eat and be excused.

Now, even though one thought one’s death could be of use, there was no passive acceptance. It was a challenge, a fight, and again resistance was built up……The mind would suffer more than the body. The struggle in the end would be between body and spirit”.

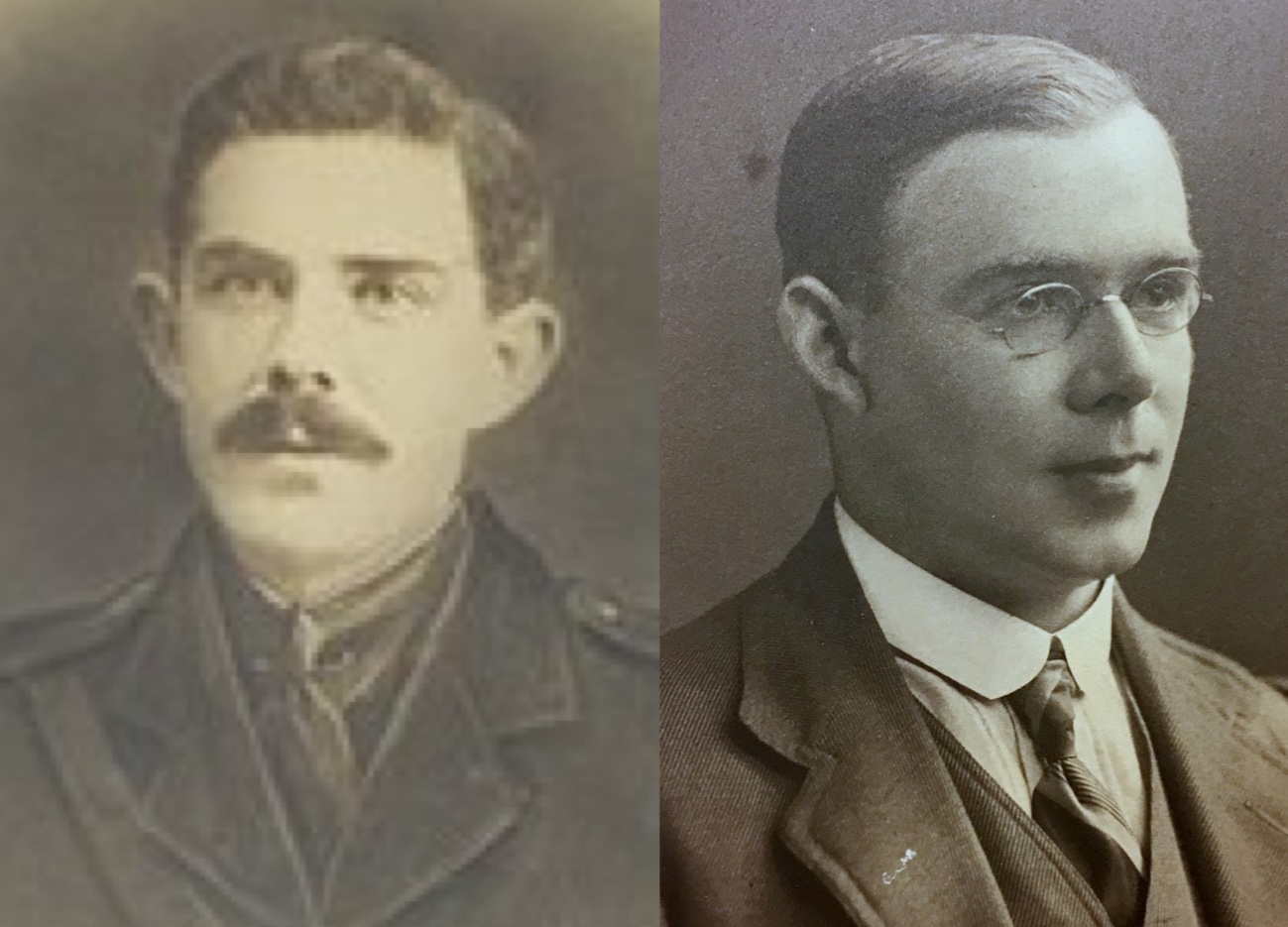

On 20 November, Denis Barry (pictured, left) died in the Newbridge Camp, and Andrew Sullivan (pictured, right) died in Mountjoy on 22 November.

When Barry died, Bishop Daniel Cohalan refused to let his body lie in a Cork church.

When Terence MacSwiney died on hunger strike in 1921, Bishop Cohalan had written in the Cork Examiner:

“I ask the favour of a little space to welcome home to the city he laboured for so zealously the hallowed remains of Lord Mayor Terence MacSwiney.

For the moment, it might appear that he has died in defeat…..

Was Robert Emmet’s death in vain? Did Pearse and the other martyrs for the cause of Irish freedom die in vain?

….We bow in respect before his heroic sacrifice. We pray the Lord may have mercy on his soul”.

At the death of Denis Barry two years later, the very same Bishop Cohalan wrote:

“Republicanism in Ireland for the last twelve months has been a wicked and insidious attack on the Church and on the souls of the faithful committed to the Church by the law of the Catholic Church”.

Denis Barry was not afforded a Catholic burial.

With the deaths of Barry and Sullivan drawing no positive response or concessions from the Free State government, the IRA command ordered the strikes ended on 23 November.

O’Malley wrote that the strike ended with no promises of release: “we had been defeated again”.

While the strike itself failed to win releases, it did begin a slow start of a programme of release of prisoners, the State being worried about the political impact of more deaths, though some prisoners remained in jail until as late as 1932.

O’Malley, writing of Tom Derrig who was in Mountjoy, related that one of the strikers there, on the last day of the strike, had asked a doctor: “What day of the strike is this?”

The doctor replied: “The forty-first”.

“Be cripes” the striker said “We bate Christ by a day!”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)