By Séamas O’Reilly (for the Examiner)

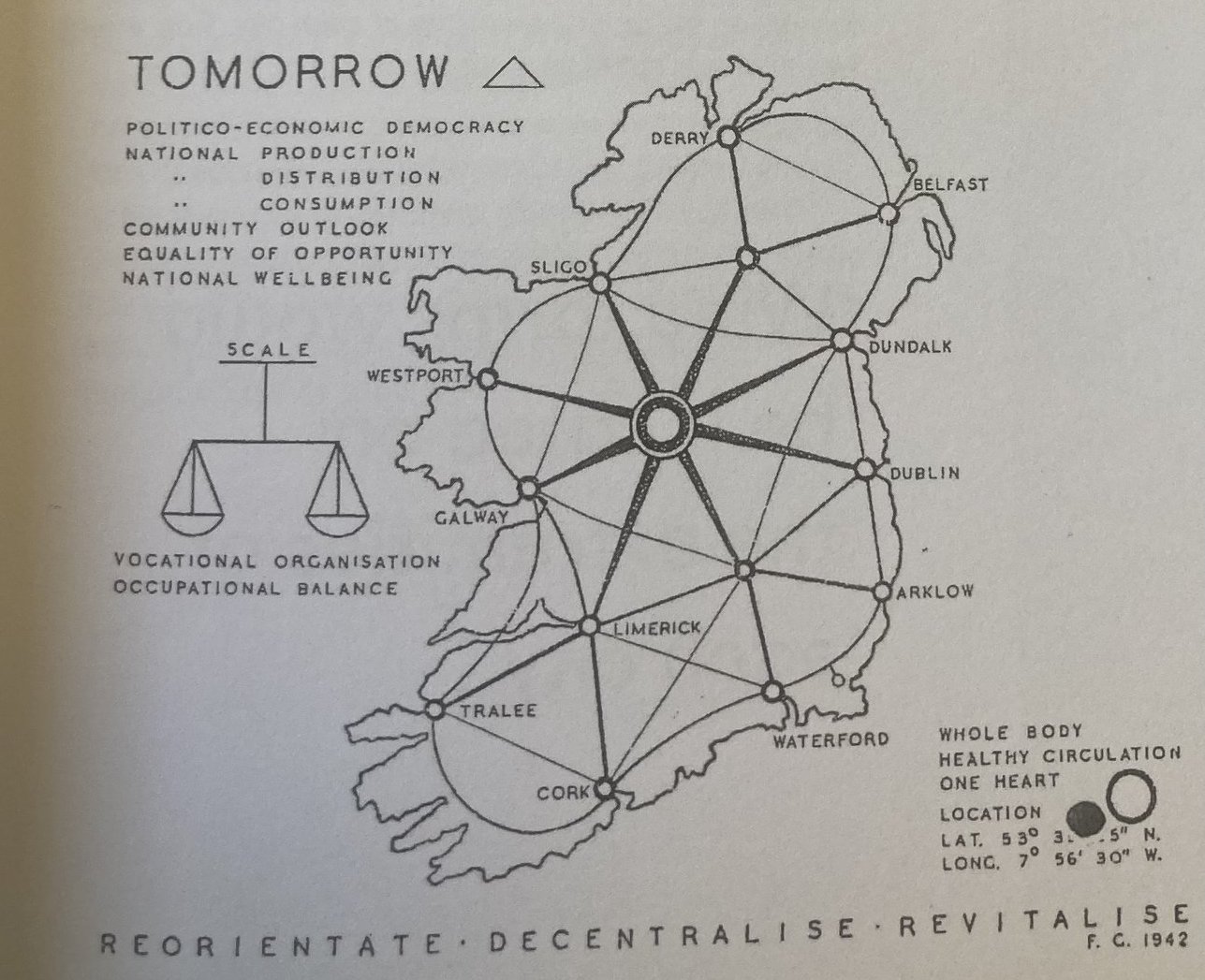

I came across a striking image this week. Shared by Dr Patrick Bresnihan, it depicted urban planner Frank Gibney’s 1942 vision for a United Ireland.

Longford is now capital, and arterial roads beam out from that new metropolis toward the towns and cities on the coasts, like chakra points on a Buddhist mandala.

I love it because I adore any glimpse at futures imagined by those long-dead, but it also made me realise how infrequently I’ve encountered such utopian plans before.

With the news that Australia’s ruling Labour party passed a motion supporting a United Ireland, it strikes me that their government is being more direct than our own, which is odd since the prospect of reunification has never seemed more likely.

In April, a Life and Times survey reported that 45% of Northern Irish people think Northern Ireland will no longer be in the UK in 20 years’ time, versus 38% who think it will remain.

Of course, believing that there will be a United Ireland in 20 years does not mean that such a thing will come to pass, or that those respondents consider it desirable.

Indeed, a large plank of unionist rhetoric invokes the spectre of reunification — a constant and, to some extent, politically necessary green-clad bogeyman, ceaselessly galloping towards them across an ever-encroaching horizon — so many who believe reunification is imminent, might well fight it tooth and nail.

We should also note the timeframe. A week is a long time in politics, and 20 years is longer still.

The same survey found that, were a referendum held tomorrow, different numbers would emerge; 35% report they would back it, while 47% would oppose. These numbers do represent a significant swing toward reunification but fall a good way short of plurality.

An IPSOS poll from last year suggested only 55% of Northern Irish Catholics would vote for a United Ireland, albeit with no timeline for said vote given.

Whatever way you hammer your abacus, it seems that a significant number of those who identify as republican would still not vote for a United Ireland if asked to do so after their next meal.

To some, these findings represent a break in the nerves of professed republicans; ‘shy unionists’ who say they want a united Ireland, but secretly keep a commemorative plate of King Charles’ coronation under the floorboards, sneaking downstairs to admire it in moments of furtively enthusiastic worship.

Much more likely, however, is that these people are steadfast in their republican beliefs, but wary of the upheaval inherent in restructuring all civic life overnight, without discussions, planning, or a useful political exchange on what its realities would entail.

Like me, most people I know back home in Derry would vote yes, but they might also wonder what happens to the NHS and the North’s unusually large public sector, which employs 27% of the population (compared to 18% of the wider UK, and 14% in the South).

Clarifying these points, and many more besides, would be an essential pull factor in turning those maybes into definites, provided of course, the Irish state wants to do so.

The push factors toward a United Ireland are clear enough. The British have run the North for a century and a performance review would not be kind.

Vacillating between hostile occupiers and absentee landlords, they’ve overseen a marked downturn in just about every metric by which a region can be measured, while the South has witnessed a comparative boom.

I won’t dwell here on their failures with regard to human rights — I have my word count to think of — but if a hundred years seems like too long a time to conceive of in human terms, I’ll just say that my grandfather was nine years old when partition happened, and he did not get the right to vote in local elections until he was 58. My parents were very nearly 30.

Even since the Good Friday Agreement, Northern Ireland has remained an abject farce of political dereliction. Its depressed economy and woeful democratic deficit, have been enabled by a ruling party willing to disband the local government any chance they get. Since 1998, Stormont has been without a functioning government for over 40% of its life.

The British people, too, evince no great desire to retain the province. As early as 2001, only 26% of Brits polled by ICM believed Northern Ireland should remain part of the UK.

In 2019, YouGov found 59% of Conservative members would let Northern Ireland leave the UK in exchange for Brexit.

Then Brexit happened, and a combination of oblivious contempt from Westminster, and laughable incompetence from unionist leaders, resulted in the latter several times backing, then immediately objecting to, deals that left Northern Ireland grafted to the Republic’s trading bloc, and therefore closer to the South in political terms than ever before.

It’s hard to see those push factors going away, so only pulls remain. The Irish government could make a compelling case for reunification on just about every metric you can name, but that would mean taking the time to articulate a vision for the island that goes beyond well-meaning platitudes and closing-time republicanism.

Steps in this direction have already been taken by the Shared Ireland initiative and in recent books by Brendan O’Leary, Kevin Meagher, Ben Collins, and Frank Connolly.

That the government is unwilling to bring such efforts to the frontline of Irish politics suggests either an inability, or unwillingness, to tackle the issue head-on, either out of fear of getting into a bunfight with Sinn Féin they fear they could not win, or — whisper it — a reluctance among Ireland’s political class to bring about the reunification that 66% of their voters say they want.

It may not be an immediate priority for TDs in Dublin, but the numbers suggest they won’t be able to ignore it for much longer. They may not be working from Longford any time soon — but in 20 years, who knows?

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)