Unionist indignation at the public use of the word ‘planter’ by visiting US politician Richard Neal has highlighted their denial of the history of settler colonisation in the north of Ireland.

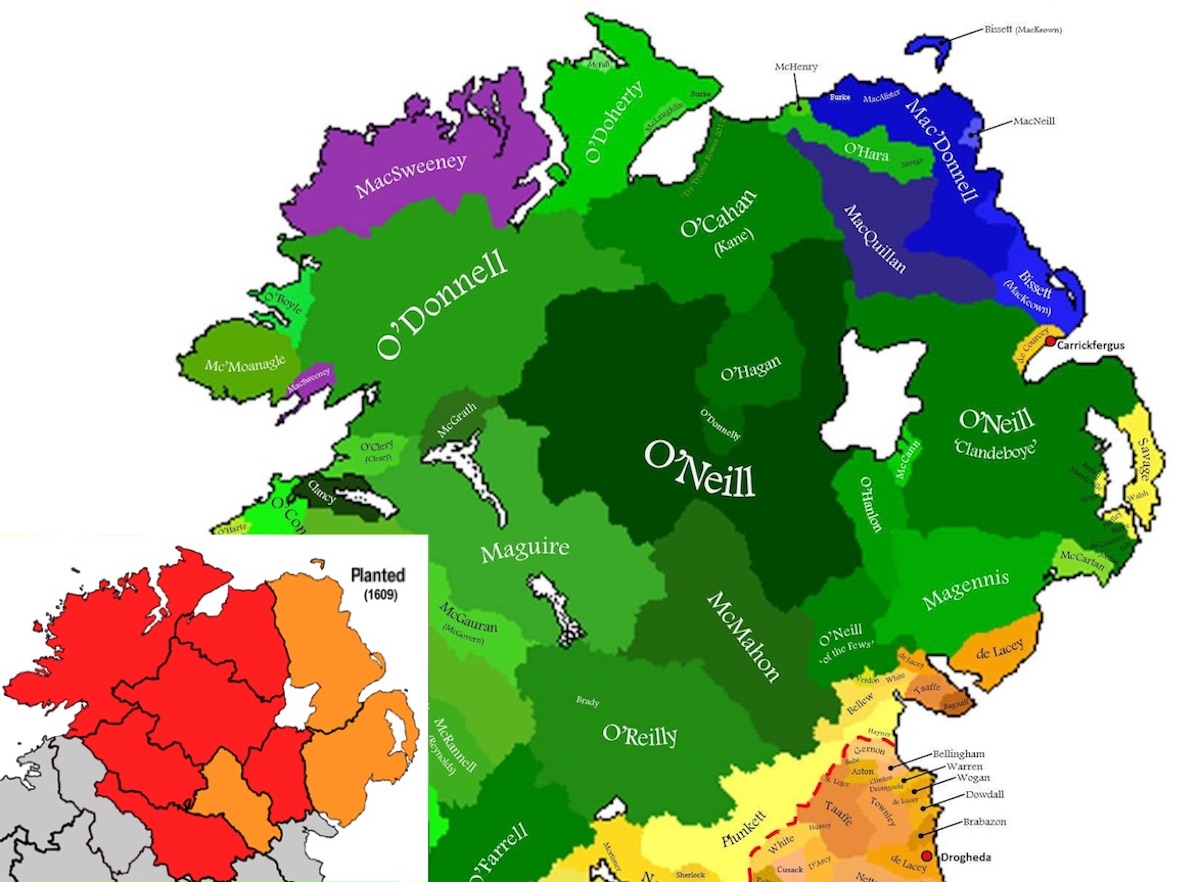

Ulster Unionist Party leader Doug Beattie said he was “deeply offended” by the term, which refers to the ‘Plantation of Ulster’, when mostly Protestant colonisers from Britain were settled by British forces in the north of Ireland on land confiscated from native Gaelic chiefs.

The 17th century example of settler colonialism involved the eviction and dispossession of the native Gaelic Irish by the forces of King James as a means of controlling and anglicising the north of Ireland and of breaking Ireland’s link to Gaelic Scotland.

Although the memory of the catastrophe has faded over the centuries, the Plantation remains one of the the major historical causes of sectarian division and violence in the north of Ireland.

Intriguingly, recent research has also pointed to Ireland’s gypsy-like Traveller community having its origins in the tens of thousands of native Irish who were displaced by the Plantation.

The phrase ‘Planter and Gael’ is now mainly used as a literary or rhetorical device to refer to the Protestant/unionist and Catholic/nationalist divide. However, the sharp unionist reaction to the use of the word ‘Planter’ in a political context has brought a new insight into the unionist mindset.

Ulster Unionist leader Doug Beattie said he was deeply offended by the use of the term by prominent US Congressman Richard Neal.

“You listen to all of that and sometimes you wonder what century Richie Neal is actually thinking through here,” Mr Beattie said. “I mean, to come up with Planter and the Gael - have we not moved on?”

The row overshadowed the continuing dispute over trade checks at ports connected to the Brexit Protocol.

Upper Bann representative Jonathan Buckley bizarrely told Congressman Richard Neal — whose grandparents emigrated to the US — that “he himself is a planter”.

DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson took the attempts at historical ‘whataboutery’ even further when he compared unionist opposition to the Protocol to the revolutionary Boston Tea Party.

Donaldson denounced Mr Neal’s efforts to defend the Good Friday Agreement as “the most undiplomatic visit I have ever seen to these shores. The language, if I may be diplomatic myself, has been unhelpful and displays an alarming ignorance of the concerns of unionism”.

When Mr Neal was asked about the unionist reaction to his comments, he noted that the terms Gael and Planter were “entirely accurate historic references”.

Nevertheless, the US congressman said his meeting with the DUP went well, and he stressed that the north of Ireland wasn’t facing a crisis.

After suggesting the protocol is a “manufactured issue” he told reporters at Stormont: “I have been in this hall many times, through far more grim moments than the one we’re currently witnessing, and I think that the role that we’ve (the US) offered, the dimension that we brought to bear, is overwhelmingly over all of these years been very helpful.”

And as Mr Neal was returning to the US, thousands of members of the anti-Catholic Orange Order ironically gathered at Stormont in a display of the continuing legacy of the Plantation.

Screens had to be erected to shield St Matthew’s Catholic Church in east Belfast during the parade to Belfast City Hall as the Orangemen provocatively marched to celebrate the partition of Ireland.

The event began with a rally which heard repeated denunciations of Irish nationalism. “No surrender!” roared the Rev Mervyn Gibson, the Order’s Grand Secretary at a rally in front of Parliament Buildings.

“Let me make it clear,” Gibson said, “if the protocol is not sorted then make no mistake - no mistake - there will be no next 100 years for Northern Ireland.”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)