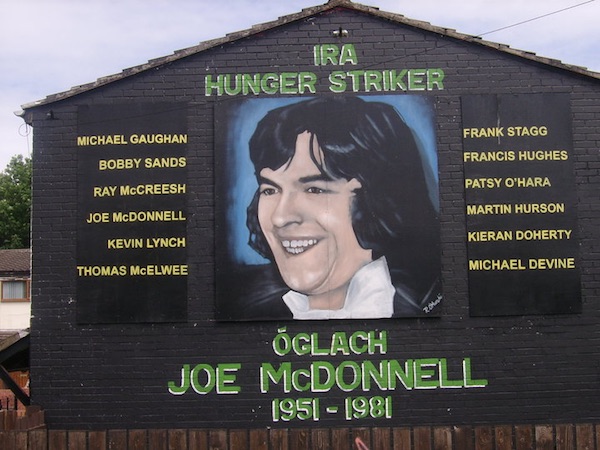

An account of the brave life of Joe McDonnell, who died on hunger strike against the criminalisation of republican prisoners, 40 years ago this week.

The fourth IRA Volunteer to join the hunger-strike for political status was Joe McDonnell, a thirty-year-old married man with two children, from the Lenadoon housing estate in West Belfast.

A well-known and very popular man in the Greater Andersonstown area he grew up, married and fought for the republican cause in, Joe had a reputation as a quiet and deep-thinking individual, with a gentle, happy go-lucky personality, who had, nevertheless, a great sense of humour, was always laughing and playing practical jokes, and who, although withdrawn at times, had the ability to make friends easily.

As an active republican before his capture in October 1976, Joe was regarded by his comrades as a cool and efficient Volunteer who did what he had to do and never talked about it afterwards.

Something of a rarity within the Republican Movement, in that outside of military briefings and operational duty he was never seen around with other known or suspected Volunteers, he was nevertheless a good friend of the late Bobby Sands, with whom he was captured while on active service duty.

Not among those who volunteered for the earlier hunger strike last year, it was the intense disappointment brought about by the Brits’ duplicity following the end of that hunger strike, and the bitterness and anger that duplicity produced among all the blanket men, that prompted Joe to put forward his name the next time round.

And it was predictable, as well as fitting, when his friend and comrade Bobby Sands met with death on the sixty-sixth day of his hunger strike, that Joe McDonnell should volunteer to take Bobby’s place and continue that fight.

RESOLVE

His determination and resolve in that course of action can be gauged by the fact that never once, following his sentencing to fourteen years imprisonment in 1977, did he put on the prison uniform to take a visit, seeing his wife and family only after he commenced his hunger-strike.

The story of Joe McDonnell is of a highly-aware republican soldier whose involvement stemmed initially from the personal repression and harassment he and his family suffered at the hands of the British occupation forces, but which then deepened - through continuing repression - to a mature commitment to oppose an occupation that denied his country freedom and attempted to criminalise its people.

It was that commitment which he held more dear than his own life.

FAMILY

Joe McDonnell was born on September 14th 1951, the fifth of eight children, into the family home in Slate Street in Belfast’s Lower Falls.

His father, Robert, aged 59, a steel erector, and his mother, Eileen (whose maiden name is Straney), aged 58, both came from the Lower Falls themselves.

They married in St. Peter’s church there, in 1941, living first with Robert’s sister and her husband in Colinward Street, off the Springfield Road, before moving into their own home in Slate Street, where the family were all born.

These are: Eilish, aged 38, married with five children; Robert, aged 36, married with two children; Hugh, aged 34, married with three children; Patsy, aged 32, married with two children, and now living in Canada since 1969; Joe; Maura, aged 28 and single; Paul, aged 26, married with two children and Frankie, aged 24 and single.

Frankie is currently serving a five-year sentence on the blanket protest in H6-Block on an IRA membership charge, following his arrest in December 1976, and is due for release this December.

A ninth child, Bernadette, was a particular favourite of Joe’s, before her death from a kidney illness at the early age of three.

“Joseph practically reared Bernadette”, recalls his mother, “he was always with the child, carrying her around. He was about ten at the time. He even used to play marleys with her on his shoulders.”

Bernadette’s death, a sad blow to the family, was deeply felt by her young brother Joe.

DATING

One of his friends at that time was his future brother-in-law, Michael, and he began dating Goretti from around the time he was seventeen.

Joe and Goretti, who also comes from Andersonstown, married in St. Agnes’ chapel in 1970, and moved in to live with Goretti’s sister and her family in Horn Drive in Lower Lenadoon.

At that time, however, they were one of only two nationalist households in what was then a predominantly loyalist street, and, after repeated instances of verbal intimidation, in the middle of the night, a loyalist mob - in full view of a nearby Brit post, and with the blessing of the raving Reverend Robert Bradford, who stood by - broke down the doors and wrecked the houses, forcing the two families to leave.

INTERNMENT

The McDonnells went to live with Goretti’s mother for a while, but eventually got the chance to squat in a house being vacated in Lenadoon Avenue.

Internment had been introduced shortly before, and in 1972 the British army struck with a 4.00 a.m. raid.

Joe was dragged from the house, hit in the eye with a rifle butt and bundled into a jeep. Their house was searched and wrecked. Joe was taken to the prison ship Maidstone and later on to Long Kesh internment camp where he was held for several months.

Goretti recalls that early morning as a “horrific” experience which altered both their lives. One minute they had everything, the next minute nothing.

On his release Joe joined the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, operating at first in the 1st Battalion’s ‘A’ Company which covered the Rosnareen end of Andersonstown, and later being absorbed into the ‘cell’ structure increasingly adopted by the IRA.

RAIDS

Both during his first period of internment, and his second, longer, internment in 1973, as well as the periods when he was free, the McDonnell’s home in Lenadoon was constant target for British army raids.

During these raids the house would often be torn apart, photos torn up and confiscated letters from Joe (previously read by the prison censor) re-read by infantile British soldiers, and Goretti herself arrested.

In between periods of internment, and before his capture, Joe resumed his trade as an upholsterer which he had followed since leaving school at the age of fifteen. He loved the job, never missing a day through illness, and made both the furniture for his own home as well as for many of the bars and clubs in the surrounding area. His job enabled him to take the family for regular holidays but Joe was a real ‘homer’ and always longed to be back in his native Belfast.

BOMBS

Part of that attraction stemmed obviously from his responsibility to his republican involvement. An active Volunteer throughout the Greater Andersonstown area, Joe was considered a first-class operator who didn’t show much fear. Generally quiet and serious while on an operation, whether an ambush or a bombing mission, Joe’s humour occasionally shone through.

Driving one time to an intended target in the Lenadoon area with a carload of Volunteers, smoke began to appear in the car. Not realising that it was simply escaping exhaust fumes, and thinking it came from the bags containing a number of bombs, a degree of alarm began to break out in the car, but Joe only advised his comrades, drily, not to bother about it: “They’ll go off soon enough.”

Outside of active service, Joe mixed mostly with people he knew from work, never flaunting his republican beliefs or his involvement, to such an extent that it led some republicans to believe he had not reported back to the IRA on his second release from internment.

The Brits, however, persecuted him and his family continually, with frequent house raids, and street arrests. He could rarely leave the house without being stopped for P-checking, or held up for an hour at a roadblock if he had somewhere to go. A few months before his capture, irate Brits at a roadblock warned him that they would ‘get’ him.

Outside of his republican activity Joe took a strong interest in his children - Bernadette, aged ten and Joseph, aged nine - teaching them both to swim, and forever playing football with young Joseph on the small green outside their home.

CAPTURE

His capture took place in October 1976 following a firebomb attack on the Balmoral Furnishing Company in Upper Dunmurray Lane, near the Twinbrook estate in West Belfast.

The IRA had reconnoitred the store, noting the extravagantly-priced furniture it sold, and had selected it as an economic target. The plan was to petrol bomb the premises and then to lay explosive charges to spread the flames.

The Twinbrook active service unit led by Bobby Sands, was at that time in the process of being built up, and were assisted consequently in this operation by experienced republican Volunteers from the adjoining Andersonstown area, including Joe McDonnell.

Unfortunately, following the attack, which successfully destroyed the furnishing company, the escape route of some of the Volunteers involved was blocked by a car placed across the road.

During an ensuing shoot-out with Brits and RUC, two republicans, Seamus Martin and Gabriel Corbett were wounded, and four others, Bobby Sands, Joe McDonnell, Seamus Finucane and Sean Lavery, were arrested in a car not far away.

Three IRA Volunteers managed to escape safely from the area.

A single revolver was found in the car, and at the men’s subsequent trial in September 1977 all four received fourteen-year sentences for possession when they refused to recognise the court.

Rough treatment during their interrogation in Castlereagh failed to make any of the four sign a statement, and the RUC were thus unable to charge the men with involvement in the attack on the furnishing company despite their proximity to it at the time of their arrest.

ADAMANT

From the day he was sentenced Joe refused to put on the prison uniform to take a visit, so adamant was he that he would not be criminalised. He kept in touch instead, with his wife and family, by means of daily smuggled ‘communications’, written with smuggled-in biro refills on prison issue toilet paper and smuggled out via other blanket men who were taking visits.

Incarcerated in H5-Block, Joe acted as ‘scorcher’ (an anglicised form of the Irish word, scairt, to shout) shouting the sceal, or news from his block to the adjoining one about a hundred yards away. Frequently this is the only way that news from outside can be communicated from one H-Block to the blanket men in another H-Block.

It illustrates well the feeling of bitter determination prevailing in the H-Blocks that Joe McDonnell, who did not volunteer for the hunger strike last year because, he said, “I have too much to live for”, should have become so frustrated and angered by British perfidy as to embark on hunger strike on Sunday, May 9th, 1981.

IMPACT

In June, Joe was a candidate during the Free State general election, in the Sligo/Leitrim constituency, in which he narrowly missed election by 315 votes.

All the family were actively involved in campaigning for him, and despite the disappointment at the result both they and Joe himself were pleased at the impact which, the H-Block issue had on the election, and in Sligo/Leitrim itself.

Adults cried when the video film on the hunger strike was shown, his family recall, and they cried again when Joe was eliminated from the electoral count.

MARTYR

At 5.11 a.m., on July 8th, Joe McDonnell, who - believeably, for those who know his wife Goretti, his children Bernadette and Joseph and his family - “had too much to live for” died after sixty one days of agonising hunger strike, rather than be criminalised.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)