By Phil Mac Giollabhain (philmacgiollabhain.ie)

This week 100 years ago on a roadside in County Cork, a small group of young men in with hardly any military training lay in wait for their enemy. History was about to be made.

The ambush is a particularly risky military operation to pull off.

If the element of surprise is lost then it usually ends in calamity for the ambusher.

The commander of the group had first hefted a rifle in the uniform of his enemy that day-the British.

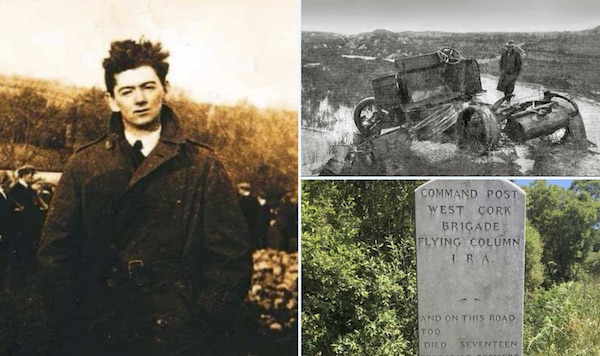

Thomas Bernardine Barry was born in Killorglin, County Kerry and he was the son of a Royal Irish Constabulary policeman.

There was nothing in young Barry’s background that would suggest that he would go down in history as an iconic IRA commander.

In 1915 he volunteered to fight for the British Empire.

Four years later he was a different type of Volunteer.

In his brilliantly written memoir “Guerrilla days in Ireland” he made no bones about his world view as a teenage recruit to the ranks of the British Army:

“In June, in my seventeenth year, I had decided to see what this Great War was like. I cannot plead I went on the advice of John Redmond or any other politician, that if we fought for the British we would secure Home Rule for Ireland, nor can I say I understood what Home Rule meant. I was not influenced by the lurid appeal to fight to save Belgium or small nations. I knew nothing about nations, large or small. I went to the war for no other reason than that I wanted to see what war was like, to get a gun, to see new countries and to feel a grown man. Above all I went because I knew no Irish history and had no national consciousness.”

Barry wrote in the same work that the terrible beauty of Easter Week changed everything for him.

Only four years later the British Empire was facing an enemy that they had trained in the Great War.

Like all successful military commanders, Barry instinctively understood Sun Tzu’s observation that

“All warfare is based upon deception”.

He was all of 23 years of age as he deployed his men at Kilmichael.

The IRA Flying Column was lying in wait that day for two vehicles full of “Auxies”.

Their full title was the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary.

Technically they were policemen.

However, this was no Dixon of Dock Green in West Cork.

This was the elite of the British Empire and the very best that they could field against the IRA.

In effect, they were the SAS of the day.

Barry wore a trench coat stood out as the lorries approached.

The ruse worked and they slowed down to what they thought was a stranded British officer.

When they were in range the ex-British soldier took a Mills bomb (hand grenade) from his pocket and lobbed it into the lead lorry.

It exploded.

The Kilmichael ambush had begun.

Barry had deployed his men into three sections and a command post.

It would tickle him in later life that his memoir was required reading at Sandhurst.

Over the last 40 years, I have regularly consulted this work.

Like all great writing it stands the test of time.

Like all good guerrilla leaders, Barry had engineered a situation where he had achieved local superiority of numbers.

It was 36 versus 18.

There is controversy to this day about whether or not the British used a “false surrender” ruse to kill the three IRA Volunteers- Pat Deasy, Michael McCarthy and Jim Sullivan.

After that Barry said that he ordered his men to keep firing.

On the Volunteers that day Jack Hennessy recalled the ambush years alter:

“I was engaging the Auxies on the road. I was wearing a tin hat [helmet]. I had fired about ten rounds and had got five bullets through the hat when the sixth bullet wounded me in the scalp. Vice Comdt. McCarthy had got a bullet through the head and lay dead. I continued to load and fire but the blood dripping from my forehead fouled the breech of my rifle. I dropped my rifle and took McCarthy’s. Many of the Auxies lay on the road dead or dying.

Our orders were to fix bayonets and charge on to the road when we heard three blasts of the O/C’s whistle. I heard the three blasts and got up from my position, shouting “hands up”. At the same time one of the Auxies about five yards from me drew his revolver. He had thrown down his rifle. I pulled on him and shot him dead. I got back to cover, where I remained for a few minutes firing at living and dead Auxies on the road.”

In Barry’s memoir, the chapter “drill amidst the dead” is wonderfully well written. Barry takes you to that bleak boreen in November with darkness falling two Crossley Tenders are ablaze and bodies strewn about the road.

He had grouped and trained his Flying Column for only a week before the ambush. These men had never been in combat before. They were shocked and shaken by what had just transpired.

Barry gripped his men and marched them up and down the road,

He had to remind them that they were soldiers in the Irish Republican Army.

The shockwaves of that stunning IRA success were felt in Downing Street.

Kilmichael had happened just one week after Bloody Sunday in Dublin.

Mick Collins had brilliantly deployed his Squad to take out the Cairo Gang, the cream of British Intelligence.

Later that day the Brits retaliated by shooting into the crowd at Croke Park.

The Auxies were stunned by Kilmichael and responded by burning large area of Cork City.

The world looked on and quickly worked out which side in the conflict should be considered to be the terrorists.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)