By former Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams (for the Journal)

Internment is a policy which has seen frequent use in Ireland. It was used by the British in the years after the 1916 Rising and during the Tan War.

It was also used by the Free State government in the 1920s and by Fianna Fáil between 1939 and 1946, as well as during the 1950s. In December 1970 Jack Lynch announced its introduction but political and public outrage forced him to backtrack.

It was used by the Unionist regime at Stormont in every decade since partition as a favoured tactic and the Unionist Prime Minister Brian Faulkner and his colleagues demanded that the British government introduce it again in 1971.

Coercive legislation and the use of torture have been key elements of British colonial policy in Ireland, Kenya, India, and elsewhere for centuries. The introduction of internment in August 1971, the arrest of over 300 nationalist men, the widespread beatings and the torture of the ‘hooded men’ was an abdication by the British Government of the primacy of politics.

Instead, Prime Minister Ted Heath handed power and control over to the Generals. The result was increasing chaos and violence.

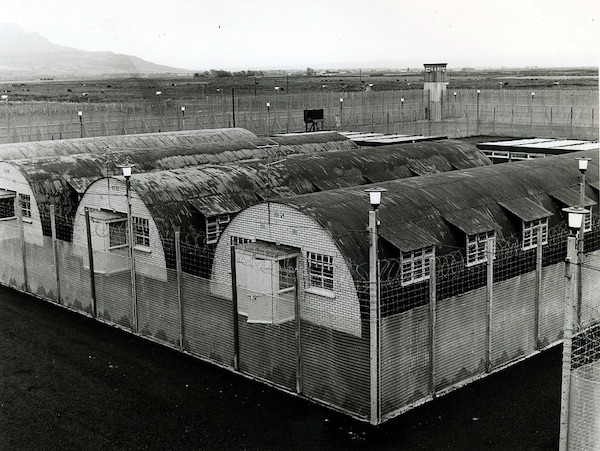

Long Kesh was built on a former British RAF base in 1971. It was a series of cages each containing four Nissan huts in which the internees were held following the introduction of internment on 9 August 1971.

The cage was surrounded by a high wire fence topped with barbed wire. The numbers of internees held in each cage varied but probably averaged around 100. Eventually, cages holding sentenced prisoners were also opened and within a few years there were 22 cages in total in Long Kesh – mostly nationalist, but four of them were loyalist.

The conditions, especially in the internee end of the camp – which was the first to be constructed – were appalling. The huts were made from two skins of corrugated tin. In the autumn and winter they were freezing cold, damp, and poorly lit.

In the summer they could be stifling. Toilet and shower facilities were primitive and the food was normally cold and of a poor standard. Most internees relied on food parcels sent in by families to supplement their diet.

The British Army carried out periodic raids on the internee cages. Scores of soldiers with batons and shields would smash their way into the huts during the night, drag men outside and force them to spread-eagle against the wire for hours. Many were beaten.

Personal belongings were ripped apart, beds urinated on, and handicrafts – which some internees made to pass the time – were destroyed.

I was first interned in 1972. On that occasion, I was in the Maidstone Prison ship in Belfast Lough. It was overcrowded, seriously cramped and with toilets that were constantly backed-up and overflowing.

The ship sat in its own sewage. Food was disgusting. We went on a hunger strike and the British closed the ship and moved us to Long Kesh. I was released to take part in talks with the British government in the summer of that year. The subsequent truce in July lasted just two weeks.

Escape

I was arrested in July 1973, beaten unconscious by British soldiers and then interned again in Long Kesh, initially under an Interim Custody Order. On Christmas Eve that year four of us in Cage 6 – Marshall Mooney, Tommy Toland, Marty O’Rawe and myself, all from Ballymurphy –tried to escape. We failed.

Seven months later in July 1974, I tried again when I swapped places with a man who came to a visit dressed like me and wearing a false beard and wig. I didn’t get far. In evidence at my subsequent trial on a charge of attempting to escape, the prison officer said:

I knew there was something wrong. When this man went in, I was looking down at him. When he came out, I was looking up at him.

In March 1975 I was convicted on the first attempt and sentenced to 18 months imprisonment. I was subsequently convicted in April 1975 of the second attempt and was given a three-year sentence to run consecutively. I was eventually released in 1977.

In October 2009 a researcher working for the Pat Finucane Centre was going through newly released documents by the British government under the 30-year rule. It was a memorandum, dated July 1974, from the Assistant Director of Public Prosecutions that advised that the interim custody order under which I was interned in July 1973, and which had not been signed by the Secretary of State himself might mean that I and other detainees “may be unlawfully detained.”

It then took ten years for the case to make its way through the British judicial system, until this morning when the British Supreme Court accepted that I had been unlawfully detained. Consequently, my convictions were quashed.

It’s a victory for my legal team and I am grateful for their efforts over many years.

However, the fact remains that internment was a setting aside of the normal rules of evidence, of trial and justice by the British government. It was open-ended. You could be detained for as long as they chose to hold you.

It was indefinite. 2,000 men and women were held in our time without due process, several died in Long Kesh, many suffered great hardship and privation and families were separated.

The resulting violence on the streets propelled the northern state into decades of further conflict. Remember, the British Paras killed 11 people, including a priest and mother of eight in Ballymurphy in the 48 hours after internment. And the Bloody Sunday Massacre happened when the British Paras attacked an anti-internment rally in January 1972.

The onus now is on the British government to identify and inform other internees whose internment may also have been unlawful.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)