A growing disparity between the coronavirus death rates in the north and south of Ireland is proof that two different approaches to the crisis are causing lives to be lost, according to academics.

The 26 Counties have generally followed the advice of the World Health Organisation, while the unionist-dominated Stormont regime in Belfast adheres to policies set by the British government.

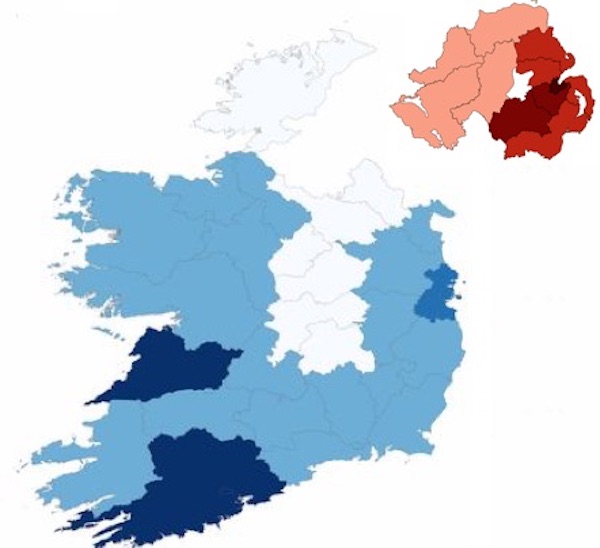

Research carried out by Michael Tomlinson, a former professor of social policy at QUB in Belfast, has shown that the death rate for Covid-19 deaths is 50% higher in the North than the South.

He said it is reasonable to assume that the North’s higher death rates result from the lower rates of testing, the lack of contact tracing and the slower application of lockdown measures compared with the 26 Counties.

“The evidence underlines the case for co-ordinated action across the island to hunt down the virus through high levels of testing and contact tracing and for stronger public-health surveillance at points of entry,” he said.

Dr Gabriel Scally, president of the Epidemiology and Public Health section of the Royal Society of Medicine, referred to the study and again called for an all-island exit strategy from lockdown to avoid “further waves of infection and death”.

He said it is vital that plans for both parts of Ireland are “compatible with, and supportive of, each other”, particularly on community testing and tracing of infected individuals, which has been virtually abandoned by London, and inward arrivals.

“The two parts of Ireland should work hand in hand to develop, as rapidly as possible, a robust network of local teams, locations for community testing and the IT and laboratory capacity that will be needed,” he said.

“The second requirement for a highly effective plan will be a jointly agreed and uniformly implemented approach to public health controls at ports and airports.”

He said “it should be inconceivable” that people could come through any port or airport in Ireland without passing through public health controls which would involve “as a minimum” taking temperatures and swabs for testing.

An island-wide, defensive response to the virus using the sea as a natural barrier has long been the key strategy for tackling infectious disease on the island. The failure to do so this time has bewildered health experts since the first cases emerged.

The North’s chief medical officer, Dr Michael McBride, this week admitted that the virus on the “single landmass” of Ireland was “behaving very similarly” in both jurisdictions “and differently to other parts of the United Kingdom”.

The Dublin government has begun checks on people entering the country at airports and seaports, but Taoiseach Leo Varadkar admitted that any controls on incoming travellers would be undermined by the possibility that infected individuals could reroute via the north’s points of entry, where there are still no checks.

With death rates in both parts of Ireland among the worst in the world, pressure for action has led to a “pilot” all-island contact tracing scheme.

SDLP leader Colum Eastwood said revelations of the slow response in Britain to the coronavirus crisis “underscores the need for a bespoke island-wide strategy” which is “not a sectarian political issue”.

But for the North’s unionist Minister for Health Robin Swann, there is still an adherence to what he called “the science that is applicable to Northern Ireland”. And there are still fears that unionists, in common with right-wing Tories, are ready to ‘sacrifice lives’ in order to unwind lockdown measures and try to jump-start economic activity.

In an ambiguous statement on Wednesday, the DUP said they want to see “close collaboration throughout the British Isles. Our approach will not be based on politics, but led by the expert evidence and advice.”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)