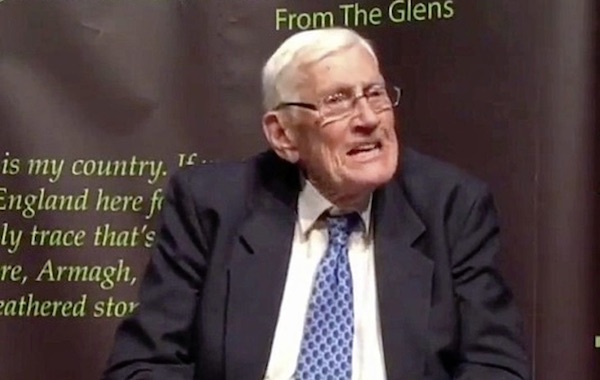

Former Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams responds to a call by former SDLP Deputy Leader Seamus Mallon that the Good Friday Agreement should be rewritten and a United Ireland should now be contingent on the agreement of a majority of Unionists. (for Leargas)

Seamus Mallon was never a big fan of the Hume-Adams talks. In 1985 Fr Alex Reid – the Sagart - tried on at least three occasions to organise a meeting between me and Mr Mallon. He delayed and delayed. Despite further efforts by Fr Reid after the Anglo-Irish Agreement was signed in November 1985, Mr Mallon finally said no to a meeting in March 1986.

On May 19th 1986 Fr Alec wrote to John Hume. John phoned Clonard Monastery the next day and the following day he met the Sagart. John and I met shortly afterwards. The Hume Adams initiative was a product of those talks. While there were other element and many more contributors the Peace Process grew out of them. So did the Good Friday Agreement.

In my opinion Seamus Mallon is not a big fan of the Good Friday Agreement. He wrongly blames it and the two governments on the decline of the SDLP and ignores other factors including his own role in this development. So his recent claim that a “united Ireland by numbers won’t work” comes as no surprise. It ignores the clear provisions of the Good Friday Agreement and undermines the equal and democratic value which should be given to every vote. Mr Mallon’s proposition also seeks to rewrite the principle of consent contained within the Good Friday Agreement.

His latest position gives an unintended insight into his role in the negotiations which led to the Good Friday Agreement. John Hume had a much more progressive and realistic position which did not accept an internal - that is a six county- settlement. That is one of the issues which we agreed on early in our talks in 1986. It was also an important element in talks between the SDLP and Sinn Féin in 1988 and in the first Hume Adams statement in April 1993. It is a central part of the Good Friday Agreement:.

Mr Mallon is now proposing that the constitutional and political landscape should be rewritten to provide unionism with an entrenched veto over the issue of rights, and in particular the right to self-determination and independence subverted by partition almost 100 years ago.

He does acknowledge the failure of partition when the rights of nationalists and republicans were trampled on. How could he do otherwise? But he repeats that mistake by raising the democratic bar on unity in favour of unionism. He hasn’t moved beyond the deeply flawed Sunningdale Agreement.

In short Mr Mallon is saying that a unionist majority can maintain partition, and the Union with Britain, but a majority which favours a United Ireland cannot achieve this without the agreement of a majority of Unionists.

As well as being at odds with the Good Friday Agreement, this stance is also in stark contrast to other majority decisions of significance taken in recent years. That is how EU treaties were decided in the South. Two recent referendums there on marriage equality and a woman’s reproductive rights were determined by a majority. The right of nationalists in the north to vote in an election for the Presidency of Ireland will be determined by a majority referendum vote later this year. If Scotland holds a referendum on the Union it too will be determined by a majority. If majorities are acceptable in those circumstances, why should a vote on Irish Unity be any different?

Seamus Mallon’s proposal would also make the task of progressing a rights based agenda in the North even more difficult than it already is. Where is the sense of “belonging” in his “shared home place” if the first thing he argues for is the relegation of the rights of Irish language speakers and our LGBTQ+ citizens in the current negotiations? How can “safety, security and comfort” be achieved if not through the core principles of the Good Friday Agreement – equality and parity of esteem?

And in case Mr Mallon has forgotten, the collapse of the Assembly and Executive in 2017, and of the talks last year, was about more than language and marriage equality rights and the crass bigotry of some in the DUP. The British government and the DUP also refused to honour agreements, particularly around the issue of legacy. And then there was the scandal of the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI). Hundreds of millions of pounds of public money squandered amid allegations of misconduct and corruption of DUP officials.

As the political momentum and demand for unity is growing as a result of demographic and political changes, greater public politicisation, and the Brexit debacle, Mr Mallon chooses this time to propose changing the Good Friday Agreement. He must know such a change will not be agreed.

He wants nationalists and republicans to “stop pushing for unity”. We should set aside our legitimate desire for unity until “there is a wider and deeper acceptance of it among the unionist community.” How will we achieve that acceptance if we don’t encourage a conversation about the benefits of unity?

Political change, and especially around such a vexed issue as partition, is only possible if the arguments for and against are debated publicly. We need a public discourse in which all of the claims and counterclaims; pros and cons can be discussed.

Mr Mallon’s proposition also misses the main achievement of the Good Friday Agreement. That Agreement is not a constitutional settlement. It never claimed to be one. By making consent a requirement for both the Union and Irish Unity it removes the constitutional veto once enjoyed by unionism. The Good Friday Agreement was and is an agreement based on equality and parity of esteem.

Of course every sensible United Irelander wants the biggest majority possible for unity. That is the most desirable outcome of a referendum on unity. By dint of their numbers unionists have a very strong position. We cannot be blind to that. Persuading enough of them to take control of their own affairs in a new agreed Ireland is a historical challenge. Being aware, sensitive and committed to winning as many unionists as possible to an agreed future in a new Ireland, and being generous and imaginative about this is the only way forward.

But it does not include inventing a new veto. Where in the tortured history of the northern state is there evidence to support the view that nationalists acquiescing to unionism ever worked? On the contrary – from the civil rights movement through the peace process, and the many periods of negotiations - progress has only been achieved when nationalists and republicans stood up for and asserted our rights alongside the rights of everyone else. Its equality Stupid!

The thrust of Mr Mallon’s argument is that a United Ireland born out of a unity referendum, with a narrow majority, risks a rerun of the past with the boot placed on the other foot. That nationalists and republicans would do to unionism what was done to us for generations. His argument is spurious and offensive. I know of no republican or nationalist who believes for one instance that we are so stupid, so narrow minded, so bigoted, so driven by hatred, as to do that. Nor do I believe that there is any popular support for a return to the conflict of the past. The last two decades have seen positive societal change. Citizens want that progress to continue.

Seamus Mallon’s willingness to change the Good Friday Agreement and reintroduce the unionist veto threatens that progress and ignores the lessons and failures of partition.

Finally, United Irelanders should continue to raise that objective wherever and whenever we can. In recent years there has been significant progress. Irish Unity is now firmly fixed on the political agenda. We will not take it off that agenda nor will we acquiesce to a new unionist veto. My preference is for a unitary state but as republicans have said many times we are open to agreeing transitional arrangements. In fact, transitional arrangements are a necessary part of our journey as an island people. As republicans we are working for a shared space - a new harmonious dispensation- in which sectarianism is a thing of the past and where people of every political persuasion and none can live, work and socialise together on the basis of equality. That’s the way forward.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)