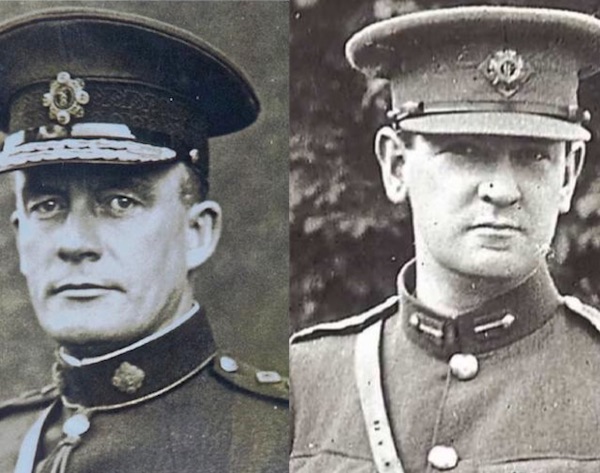

100 years ago this week, Ned Broy smuggled Michael Collins into the headquarters of the British police in Ireland. It was a key turning point in the War of Independence. (By the Collins 22 Society)

Throughout Irish history, rebellions were always failures because of cowardice, drink, and most ominously, informers. Returning from Frongoch Prison in Wales with the other survivors of the failed 1916 Rising, Michael Collins realised this. Britain had always been able to either place spies in rebel parties or else succeed in enticing Irishmen to ‘rat out’ their colleagues for money and protection. With his own intelligence network, he took on, and beat, Britain at its own game.

Michael Collins was appointed the Director of Intelligence of the Irish Volunteers in January 1919. By this time, he had already laid much of the groundwork for his intelligence network.

Collins had penetrated the Irish and English postal, telephone and telegraph systems. Letters and dispatches could be moved to various contacts by certain train inspectors. The railway workers were organised so effectively that the military frequently had to move troops and stores by road, which would play into the hands of the IRA ambushes as the war intensified. The trade unions were mobilised to hamper police and military movements by road, rail and sea. For many months the army had to tie up thousands of men on the major ports as the dockers had paralysed all attempts to land stores.

One of Collins’ key activities was gun running. He established a network of agents across the British Isles using his IRB (the Irish Republican Brotherhood) connections. His secret channel was dubbed the ‘Irish Mail’. Gelignite from Wales and England came carefully packed in tin trucks, rifles came in wicker hampers, revolvers and ammunition in hand luggage. In December 1918 a munitions factory was set up in the cellar of a bicycle shop in Dublin, with Collins taking over the operation of it several months later.

The most important event in 1918 for the intelligence network was Collins’ meeting in March with Detective Ned Broy of the DMP (Dublin Metropolitan Police). The police in Ireland was divided into the RIC (Royal Irish Constabulary) throughout the country and the DMP in Dublin city. Broy gave Collins a detailed, inside knowledge of the British police system in Ireland. He learned how the system worked and how the police were trained. Particular attention was paid to the special ‘G’ division of the DMP, whose job it was to keep watch on any national movements. Anyone suspected of being an agitator had an ‘S’ placed after their name and their movements were followed by the ‘G’ Men. Each ‘G’ man transferred his files every night to ‘a very large book’, of which Broy had access to. Collins was from then on able to get a copy of every secret file that went into the very large book. As well as Broy, Collins got in contact with two other detectives who were based in Dublin Castle.

Collins set up an intelligence office at 3 Crow Street over a print shop. Liam Tobin became the Chief Intelligence Officer. The office’s initial task was to gather as much information as possible about the DMP, especially ‘G’ division. Collins continued to recruit agents for his intelligence network. The chief clerkess at British military headquarters in Cork provided a vast amount of information on raids, spies and informers. A typist in Dublin Castle supplied information concerning field security and counter-insurgency operations, as well as personal details of British intelligence officers. On April 7th 1919, Detective Broy smuggled Collins into the Detective Headquarters in Brunswick Street, where he spent the entire night going through police records. Collins was the first Irish revolutionary to have the entire modus operandi of the British police in Ireland laid out before him.

On April 9th, a new and bloodier phase of the intelligence war began. Acting on Collins’ orders, a number of ‘G’ men were warned by the Volunteers against an excess of zeal. ‘G’ men who did not comply would pay with their lives.

Strict rules were laid down for Squad shootings. Assassinations were a last resort, coming after repeated warnings to the target. Once the order to shoot was given, the Squad would study the locale carefully and work out where and when the shooting would take place. After a job the guns would be dropped in the pockets of ‘the Black Man’, a former boxer who perpetually walked the streets of Dublin.

On July 30th, Detective Sergeant Smith of the ‘G’ Division was shot dead by the Squad on the authority of Dail Eireann. On September 12th, Sergeant Daniel Hoey was shot dead outside of Police Headquarters at Brunswick Street. Both Smith and Hoey had disregarded several warnings from Volunteers. As a result of these killings, political detectives became less inclined to go beyond the letter of their duty, or taking any risks in its execution. Collins explained his strategy in 1922:

“Without her spies England was helpless... Spies are not so ready to step into the shoes of their departed confederates as are soldiers to fill up the front line in honourable battle. And, even when the new spy stepped into the shoes of the old one, he could not step into the old one’s knowledge... We struck at individuals, and by doing so we cut their lines of communication, and we shook their morale.”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)