The safe arrival of a major civil rights march into Derry, after it had come under repeated attack by the B-Specials, inspired Liam Hillen to write one of the most famous slogans of the conflict. Liam passed away this week, almost 50 years to the day after those historic events.

The march had been organised by the People’s Democracy movement, inspired by the Selma to Montgomery marches in the United States led by Martin Luther King.

Forty people, many Queen’s University Belfast students and graduates, had left Belfast for Derry on New Year’s Day. Their numbers grew as they marched, harassed by loyalists and rerouted by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).

A number of those who marched recalled the events in a recent interview with the Irish Times.

On January 4th they were ambushed at Burntollet, near Derry. “There was a police jeep in front of us, and a group of 5 or 6 RUC men who stopped the jeep and took out shields and helmets and put them on, and that’s when I realised something more serious was happening,” said Michael Farrell.

Stones began raining down. Up to 300 loyalists swarmed on to the narrow country road. “I saw clubs, but other people saw clubs with nails through them, and iron bars.

“The police moved back from the side of the road, leaving the march open to attack,” says another marcher, Vinny McCormack. “It was almost like a military operation, and that’s what startled us. The rocks came first of all, and then the attackers.”

Soon, they were being attacked with batons. Many of the attackers wore the white armbands used by the auxiliary police force, the B-Specials.

McCormack took refuge in a freezing river. “I was very frightened. So long as we were in the river we seemed to be fairly safe, but I was very, very frightened,” he says.

“I could see people with blood pouring out of their heads,” says Farrell, “and people were saying to me that so many had been taken to hospital.

“I saw several police vehicles there with police sitting in them. And there was a crowd of guys with white armbands on [B Specials], with their clubs, smoking, and having a rest and some of them were chatting to the police.”

Farrell was shocked. “There had been a very brutal attack, and here the police were just sitting fraternising with the attackers.”

SENSE OF VICTORY

The attacks continued as the marchers made their way into Derry city through the predominantly Protestant Waterside - at Irish Street, and at Spencer Road.

A then 13-year-old schoolboy, Paul O’Connor, remembers walking out with two friends, still dressed in his St Columb’s College uniform, to meet the marchers.

“A lot of people were bleeding, a lot of people were injured, and they’d clearly just gone through something pretty awful. My vivid memory is of us all bolting down that road, everybody shouting, ‘Run, run’.”

O’Connor was unhurt; Farrell was hit “by a big chunk of stone” and knocked unconscious: “I remember one of the nurses saying to me, ‘You people deserve this, bringing trouble into our town’.”

However, several thousand people had gathered in Guildhall Square to welcome the remaining marchers. “It was a big moral victory,” says O’Connor. “It was very emotional.”

Bernadette Devlin (now McAliskey) says that, when speaking from the stage, she used the phrase, ‘We have marched from the capital city of Northern Ireland to the capital city of its injustice.’

Hours after the march had reached Derry, at about three o’clock in the morning on January 5, 1969, word went out that the B-Specials were planning to move into the Bogside.

CORRECTING THE RECORD

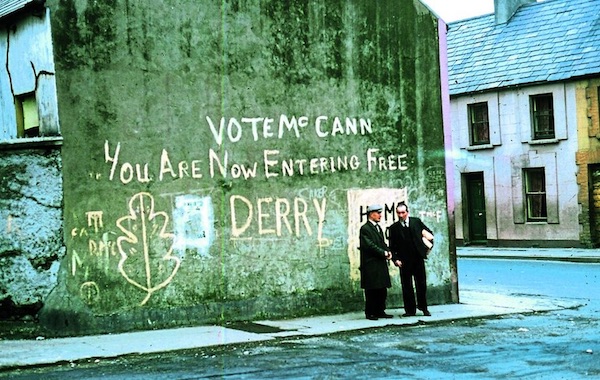

In an interview with the Derry Journal, Liam Hillen, who has recently passed away, recalled that he was with veteran activist Eamonn McCann and a few others in the freezing cold when he happened to see this house with a light coming from the living room.

“Myself, Eamonn McCann and a few others went inside to get a bit of a heat. I said to Eamonn: ‘Do you know something, I am fed up standing around doing nothing’. He said to me, ‘why don’t you put a slogan up on the wall’. A few suggestions included, ‘We Demand Free Beer’ and ‘RUC Out’.

Eamonn then said: ‘Why don’t you write: you are now entering Free Derry. There was a young boy with us and he told us that his granny lived nearby so off we went and got some paint.

“When we came back, I remember saying to McCann, ‘Is there one or two rs in entering?’ That was when I painted, ‘You Are Now Entering Free Derry’ on the gable end. It was perfect.

“I think it was a few months later that the Defence Association commissioned ‘Caker’ Casey to paint over my slogan but I was the first person to write the words on the wall.”

Eamonn McCann was among those to pay tribute to Mr Hillen this week.

He said: “Liam made a significant contribution to the way the civil rights period is remembered today.

“Liam is the man who first wrote, “You Are Now Entering Free Derry”, on a gable wall in the Bogside, early on the morning of January 5, 1969.

“I spoke last week to some of those still around about what sort of ceremony or gathering at Free Derry Wall would be suitable for marking the 50th anniversary. But it wasn’t to be.

“I feel it important to acknowledge Liam’s role because, on account of a misunderstanding, I failed to do so when my book, ‘War And An Irish Town’, was first issued in 1974. The book was republished just a month ago. A preface to the new edition tries to set the record straight.

“Sometimes inaccuracies which seemed too trivial to matter turn out to matter very much to somebody. I attributed the writing on a gable wall of the slogan, ‘You Are Now Entering Free Derry’, to Bogside activist ‘Caker Casey’.

A few years ago, I was approached in a city centre pub by a man saying, ‘I have a bone to pick with you, McCann.’ He introduced himself as Liam Hillen. It was he who had inscribed the slogan, he insisted. ‘Do you not remember me coming over to you and asking, “Is there one r or two rs in entering?”

In a flash, the memory came back. “Free Derry Wall has assumed iconic status in the meantime,” he said. “It’s right that Liam’s role should be acknowledged.”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)