The general election of 1918 provided Sinn Fein with a democratic endorsement both to establish Dail Eireann and proclaim a republic. By Ryle Dwyer (for the Examiner).

The general election of 1918 had possibly the most profound impact on Irish politics of any general election.

For decades Irish politics had been driven largely by nationalist constitutional policies, but these were suddenly discarded in 1918.

A protest march against conscription for the First World War in Ballaghaderreen in 1918. The first indication of the election was on November 14, 1918, three days after the Armistice was signed, ending the first world war. Prime Minister Lloyd George told the House of Commons that he was asking the king to dissolve parliament on November 25 and call a general election for December 14.

Irish politics had been undergoing revolutionary influences in the previous couple of years. In the wake of the Easter Rebellion, the Irish nationalist population was disillusioned by the 16 executions. The last of those was Roger Casement, who had courageously returned to Ireland from Germany in a futile attempt to stop the Rising.

Public disenchantment found expression in four Sinn Fein by-election victories in 1917 -- Count Plunkett won in North Roscommon, Joe McGuinness in Longford South, Eamon de Valera in East Clare, and W T Cosgrave in Kilkenny City.

After the Sinn Fein party united under the leadership of de Valera in October 1917, the party suffered a series of reversals, losing the next five Irish by-elections, before the British made the political blunder of trying to introduce military conscription in Ireland.

On April 9, 1918 Lloyd George introduced a bill designed to extend the maximum age for conscription of men in Britain from 41 to 51 years of age. The bill contained a clause stipulating that the government “may by Order in Council extend this Act to Ireland”.

The prime minister said it was unreasonable that married men with families should be conscripted in Britain while all men in Ireland were exempt. Consequently, he told the House of Commons that “the Government shall, by Order in Council, put the Act immediately into operation” in Ireland.

The bill was rushed through Parliament in little over a week. The Irish Nationalist Party walked out in protest, which was tantamount to an endorsement of the policy of abstention already adopted by Sinn Fein’s four members of parliament. As new legislation would be applicable to all men under 51 years, including clergy and religious brothers, the Catholic Church reacted indignantly here.

The hierarchy effectively sanctified an anti-conscription campaign by directing the clergy to “announce details at every public Mass” of the time and place of a local public meeting at which people would formally take an anti-conscription pledge the following Sunday. This pledge, which was secretly drafted for the bishops by de Valera, read: “Denying the right of the British Government to enforce compulsory service in this country, we pledge ourselves solemnly to one another to resist conscription by the most effective means at our disposal.”

The campaign was further bolstered when labour representatives staged a one-day national strike two days later, bringing the country to a virtual standstill. Massive public demonstrations were held at which the anti-conscription pledge was administered.

In the face of such united opposition, conscription would likely have required more men to enforce it than would be conscripted. Consequently, that Order in Council was never introduced for Ireland.

While the Nationalist Party backed the campaign, Sinn Fein got the bulk of the political credit, after the British rounded up more than 80 of the Sinn Fein leaders and deported them to Britain.

The British said Sinn Fein was involved in some kind of plot with the Germans. No evidence of this was ever produced, yet all were imprisoned without ever being charged with anything, much less brought before a court. It was a gross perversion of justice.

Sinn Fein’s star had seemed to be on the wane in early 1918, but the conscription controversy reversed the party’s fate.

At the height of the crisis in April, Patrick McCartan won a North King’s County (Offaly) by-election for Sinn Fein, and the party founder, Arthur Griffith, went on to win the next by-election in East Cavan on June 20, 1918.

When the world war ended on November 11, 1918, it might have seemed that Sinn Fein would be in poor shape to contest a general election with so many of its leaders in jail. As the Armistice was being signed, Sinn Fein was holding an enthusiastic general election convention at the Mansion House, Dublin.

Inside, Sean T O’Kelly moved a resolution calling for “the restoration of Ireland’s independence and the immediate release of all political prisoners”. He then went on to call for the political eradication of the Nationalist Party, because it would not support the demand for an Irish Republic.

“There was only one thing for them, and that was a complete wiping out in every constituency in Ireland,” O’Kelly said. “Nothing less could satisfy Sinn Fein.”

Before parliament dissolved on November 25, James Dillon, the leader of the Irish Nationalist Party, echoed the call for the release the Sinn Fein prisoners. They were “arrested in connection with the alleged German plot which everybody now looks upon as a pure invention,” Dillon told the House of Commons.

He clearly saw ominous prospects for his own party, as many of the prisoners were being selected to run for Sinn Fein in the general election.

“The arrest of these men and their detention in gaol has contributed enormously to the troubles in Ireland,” Dillon added. “It has undoubtedly very seriously injured our election prospects.”

The national newspapers were mostly alarmed by the election prospects.

“The one predictable outcome of the General Election,” The Irish Times proclaimed in an editorial next day, “is the triumph of Sinn Fein in most of the Nationalist constituencies.” Of course, this was not a prospect that The Irish Times welcomed, as it had always been seen as a Unionist newspaper.

The Cork Examiner and The Freeman’s Journal both seemed to conclude that the Unionists would be the big winners. In its editorial that day, The Cork Examiner feared Sinn Fein could undermine the Irish people with its abstentionist policy because it “would result in their Parliamentary disfranchisement.”

This “would set Sir Edward Carson up as the spokesman of the Irish nation”.

The same day The Freeman’s Journal blamed Sinn Fein for playing into the hands of the Unionists and Lloyd George in a way that “will enable him utterly to defeat the cause of National Self-Government.”

The election would decide “whether Ireland has the intelligence to penetrate the hot air rhetoric of Sinn Fein” or endure the consequences of as great a mistake that “ever disgraced the history of a nation”.

The Irish Independent, on the other hand, was blisteringly critical of the Nationalist Party that day. “The poor old tottering Irish Party do not know what exactly they want,” the newspaper declared its editorial. “No independent Nationalist will be sorry if at last the Irish people rid themselves of the Party which, by blundering and stupidity, lost every opportunity presented to them and earned contempt not only for themselves but for the country.”

While those Sinn Fein candidates who were in jail were unable to speak for themselves, they received enthusiastic support from local priests on the election platforms, in view of the close connection between the party and the Catholic Church during the conscription campaign.

Most people believed it was as a result of the conscription campaign that they were in jail. To a degree, therefore, their campaigns were virtually sanctified.

The first major development of the campaign was the close of nominations on December 4 when 25 Sinn Fein candidates were immediately elected, as no one had been nominated to oppose them. More than 40 MPs decided not to stand for re-election. They obviously saw the writing on the wall.

“The great features of the General Election in Ireland are the keen fight in Ulster in which every seat is being contested and the Party’s collapse in Munster,” the Irish Independent noted. It was “almost a walkover for Sinn Fein” in Munster, where the party won 17 seats uncontested.

The winners included such notables as Padraic O’Keeffe, Terence MacSwiney, David Kent, Michael Collins, and Diarmuid Lynch in Cork, Austin Stack, Fionan Lynch, and Piaras Beaslai in Kerry, along with Con Collins in Limerick.

Only seven of the province’s 24 seats were contested. Two of those were in Cork City, two in County Tipperary, two more in Waterford, and the other contest was in County Limerick.

The ensuing campaign was a lacklustre affair outside of Ulster, because nearly all the contests in the rest of the island were between Sinn Fein and the Nationalist Party, and most of the Sinn Fein contestants were either in jail, or “on the run”. John Dillon’s campaigning in East Mayo commanded considerable attention, because he was being opposed there by the absent de Valera, who was in Lincoln Jail.

“I want not only to win this election -- that I am perfectly certain of -- but to win by a decisive and overwhelming majority, “ Dillon declared in Ballaghaderreen at the start of the campaign. “The result of this election will have a very exceptional effect on public opinion throughout the world, and particularly in America.”

Some 6,000 people gathered for Dillon’s rally in Castletown, Co Mayo, on December 11. Nationalists claimed the enthusiasm of the meeting was indicative of their overwhelming strength in the constituency, despite the contrary claims of Sinn Fein.

The Catholic Church in Ulster pleaded with the Nationalist Party and Sinn Fein to divide some of the constituencies in Ulster between them, especially eight constituencies in which the Catholic nationalist population formed a majority. But the Unionists would likely win the seats, if the Sinn Fein and the Nationalist Party competed against each other. Cardinal Michael Logue and seven northern bishops appealed to the Lord Mayor of Dublin to get the two parties to divide up the constituencies between them.

The Lord Mayor got Eoin MacNeill and John Dillon to meet at the Mansion House, and they agreed that each party would contest just four of those constituencies, but they could not agree on which constituencies would be assigned to each, so Cardinal Logue suggested a division. By the time the two party headquarters had agreed to this proposal, all of the candidates had already been formally nominated, and it was too late to remove their names from the ballots.

The two parties agreed, however, that they would support the candidates designated by the cardinal’s division of the constituencies. They called on their supporters to honour this agreement.

The Nationalist party won its four constituencies, but Sinn Fein won only three, because the arrangement broke down in East Down, where the Nationalist candidate polled 4,321 votes, ahead of the 3,876 for Sinn Fein’s man, whom he was supposed to support. The seat went to the Unionists candidate with 6,997, even though his vote was 1,200 votes less than the combined total of the other two.

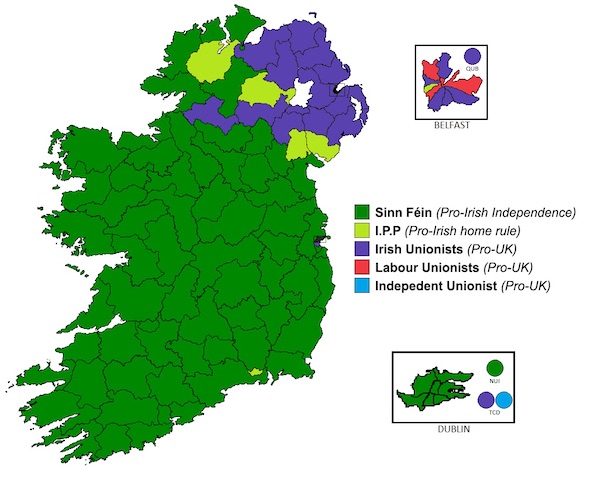

Unionists won 22 of Ulster’s 37 seats, with Sinn Fein taking 10, and the Nationalist Party the other 5. Afterwards the verdicts on the election appeared, as if the whole thing had been a foregone conclusion in the rest of the country, but that was not how many of the editorial writers saw it at the time.

“The Irish people, on the one hand, are invited to support a practical policy of Dominion Self-Government, which is the country’s one chance of national salvation, and on the other, they are asked to seek a mirage Republic,” The Cork Examiner declared in its election-day editorial. “Today they will be called upon to make their choice in the polling booths, and to say whether they prefer a policy of rainbow-chasing, or one which offers practical tangible advantages in the present and will ultimately secure for them the liberty that they so earnestly desire!”

There was no doubt Sinn Fein was the big winner outside of Ulster, taking 62 of the 64 seats in the other three provinces. That included all thirteen seats in Connaught, where de Valera trounced James Dillon in the constituency that Dillon had represented for 33 years. de Valera won by almost two-to-one, with 8,975 votes to Dillon’s 4,513.

Sinn Fein won 26 of the 27 seats in Leinster, losing only in Rathmines, Dublin, to Sir Maurice Dockrell, the Unionist candidate. William Redmond of the Nationalist Party retained his late father John Redmond’s old seat in Waterford City, but Sinn Fein won the other 23 seats in Munster.

Sinn Fein’s winners included Madame Markievicz, who comfortably won her contest in Dublin, thus becoming the first woman ever elected to the British Parliament. She was actually the only woman elected in that general election in which women first got the vote.

In overwhelmingly replacing the Nationalist Party with revolutionary republicans, it was the most significant general election in 20th century Ireland, because it provided Sinn Fein with a democratic endorsement both to establish Dail Eireann and proclaim a republic.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)