A former internee recalls Operation Demetrius, when the British Army violently rounded up and imprisoned hundreds of nationalists and caused almost 7,000 to flee their homes.

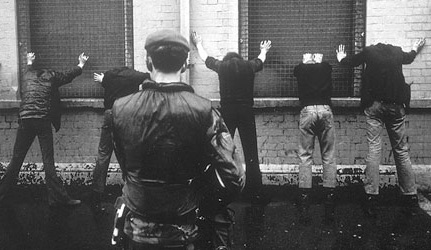

Internment without trial was introduced in the early hours of August 9th 1971 by ‘Northern Ireland’ prime minister Brian Faulkner and at dawn, 1,800 British soldiers, backed by the RUC, raided homes across the North, arresting nationalists and republicans.

It was designed to combat the rising number of IRA attacks across the North. 342 men were arrested on the first day of internment, which was code named ‘Operation Demetrius,’ by the British army. The RUC were acting on out of date information at the time and, as a result, many of those arrested had little or no connection to the IRA.

The first internees were taken to the Crumlin Road prison and the Maidstone, a prison ship moored in Belfast Lough. As the numbers rose the authorities hastily converted a former RAF base at Long Kesh into a prison and the internees were transferred there. It was later to become the main prison in the North and a focal point of the Troubles.

Gerry McCartney, a member of a prominent republican family in Derry, was not picked up when internment was introduced in August 1971 because he was on holiday. He managed to avoid internment for three years but was arrested in 1974 and sent to the cages of Long Kesh.

“The day internment was introduced I was on holiday in Bundoran and reports came through the grapevine about what was happening. Internment did not come as a surprise and there had been reports beforehand that it was about to be introduced,” he explained.

The leading republican also said internment was used almost exclusively against nationalists.

“The Irish government also wanted loyalists interned but Faulkner baulked at the idea. Thousands were interned throughout the five year period but only 104 loyalists were among them, despite the fact that the first bombs were exploded by the UVF and they were also responsible for the first deaths. It was a one-sided tactic because loyalists were not seen as a threat to the state,” he said.

Mr McCartney explained that he had been “on the run” for two years before he was interned. “I did not stay in my home from mid 1972 but it still got raided. At Christmas 1973 my parents house was raided five times on Christmas day. Families bore the brunt of the house raids. I was well aware of the risk of arrest but it was parents who had to go through the regular raiding of the house.

“When I was arrested in September 1974 I was in Creggan and I was taken to Ballykelly and then served with an internment order and taken to the camp. At that stage there was a protest and we were throwing the food out of the cages,” he said.

During his internment, Mr McCartney was involved in one of the most dramatic incidents to take place in Long Kesh, the burning of the camp.

“I went in at the end of September and on October 15th we burned the camp. We fought with the British army and they coralled us into a pitch at one end of the camp and we had nowhere to go. That’s when they dropped the CR gas on us. Questions have to be asked about the use of the gas. The British say they never used it operationally but I know for a fact they did because it was used on me. They did not use it to regain control of the camp because they had already had us coralled. They were just experimenting on us,” he explained.

The Derry man also said internees were often brutalised in Long Kesh.

“The cages were raided every six weeks, usually at 4am when the soldiers would come in and beat the beds and you have to leave the hut and run to the canteen hut through a gauntlet of soldiers and dogs. If they perceived you were resisting they stood you out against the wire,” he said.

He also said when it was announced that the internees were being released it created an uneasy atmosphere in the camp.

“The first indication that it was coming to an end, as they said, was in February or March 1975. William Whitelaw said it would be phased out by Christmas. It was like a new kind of torture because we were getting released in batches but you didn’t know when. They released batches of six people every Tuesday and Friday. Every day you woke up wondering if it was going to be your week to get out,” he said.

Mr McCartney also said he believes it is important for young people to learn about the history of internment. “It is often said that if you do not know about your past then you are in danger of repeating it and I think that is why we have to look back at this.”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)