By Danny Morrison (for the Irish Times)

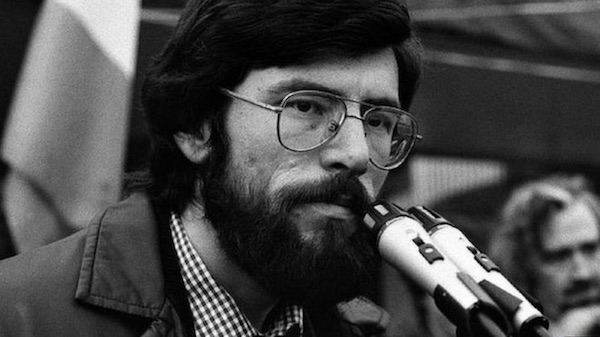

I’m sure that there is a little nervousness within Sinn Fein as Gerry Adams steps down as president of the party, having led it to great electoral success across Ireland, and having been, along with the late Martin McGuinness, at the forefront of the republican struggle for decades. He was also one of the Republican movement’s most astute and experienced negotiators, as even his opponents acknowledge.

To know Gerry Adams you have to understand the nationalist experience in the North. There is a huge difference between reading about the life of a second-class citizen and actually living that experience, with the daily humiliation and poverty associated with it.

It is so easy, when you have your freedom, to tell those who haven’t how they should have lived, reacted or behaved. It is hypocritical to lecture them when you yourself owe the freedoms you enjoy, and have institutions with which you can identify, solely because an earlier IRA fought the British who once ruled the entire country.

We in the North were sacrificed so that 26 counties could have their freedom. That’s how and I others who experienced unionist government attacks on civil rights marchers, the burning of our homes, the killing of our neighbours by the RUC, and the British army curfew of the Falls, saw it. No one came to our aid.

But, of course, in the preferred, anti-republican, anti-Sinn Fein, anti-Gerry Adams narrative, it all begins with the IRA firing the first shot and not the widespread, relentless state violence and institutionalised discrimination that preceded that first shot. After the conflict erupts terrible, yes, unconscionable acts are carried out - by all protagonists.

A resolution only became possible when the British in the 1990s finally accepted that there was no military solution and that talks had to include all representatives, including Sinn Fein.

Gerry Adams was crucial in persuading the IRA to cease fire, to eventually disarm, and to convince republican activists and supporters to accept compromise.

In 2001, Sinn Fein overtook the SDLP as the party of choice of the nationalist community, and in every subsequent election that lead has grown. However, the response of Fianna Fail and Fine Gael to that mandate is not to seek an agreed or united approach to resolving outstanding issues (as they did with the SDLP) regarding the future of powersharing, equality and rights.

The response has been to be even more hectoring and hostile towards the party, post-Good Friday, and especially in its demonisation of Adams. These parties have yet to “ceasefire” and the reason is not unrelated to the electoral rise of Sinn Fein in the Republic. They now hope to denigrate Adams’s successors with the same obloquy. Yet, when it comes to legacy and the truth when was the last time they called for the British government to release its files on the Dublin-Monaghan bombings or to publish Lord Stevens’s 3,000-page report into collusion?

I have known Gerry Adams 46 years. In 1975, as editor of Republican News, I asked him would he write a weekly column from Long Kesh, which he did under the pen man Brownie. A year later I published his first pamphlet, Peace In Ireland.

After his release in 1977 we worked together in building and expanding Sinn Fein and in challenging the party’s Eire Nua policies which we considered unrealistic.

But a lot of our energy from day one was devoted to the critical situation in the prisons where protests were taking place because of the withdrawal of political status. Gerry and I had been lobbying nationally and internationally, met politicians and trade unions and had several meetings with Cardinal O Fiaich who found it impossible to deal with Mrs Thatcher. We had also met John Hume. British intransigence eventually led to the 1981 hunger strike when 10 prisoners died.

Dealing with the British, who had been in indirect touch with us after the first four deaths, but who were still intent on defeating the prisoners, was tense, nerve-wracking and one bitter lesson in duplicity. I collapsed in early July and ended up in a Dublin hospital for a month. How Gerry and Martin maintained their composure and sanity throughout those heart-breaking months of their comrades’ deaths is incredible and great testimony to their personal fortitude and focus.

The election of Bobby Sands in the North and Kieran Doherty in the South then became the springboard for a more strategic approach which saw us participate in the 1982 Assembly elections, winning five seats.

After stating that it could not talk to us unless we had a mandate, the response of the British government to our successes was to exclude Gerry, Martin and myself from entering Britain; to ban us from receiving departmental papers for constituency business; to condemn anyone who spoke to us; then to introduce the broadcasting ban on Sinn Fein.

At the same time, our elected representatives were also shot in their homes or while attending council business. Gerry himself was shot three times and his home was attacked with a hand grenade.

Of our delegation in face-to-face talks with the SDLP in 1988, I was the least enthusiastic. I saw no point and could envisage no end to the conflict. But, I was wrong. I had been aware of Fr Alex Reid in the wings for many years, read the different papers that he wrote - about alternatives to armed struggle, Dublin becoming a key player, etc.

At leadership level Gerry Adams drove that ongoing discussion and, generally, won over the majority of republicans, many of whom were sceptics, to a peaceful, pragmatic approach (and a process of reconciliation).

He now hands over to younger leaders a very healthy, radical, republican all-Ireland party. They have their work cut out: averting the threat that Brexit poses; and trying to securely re-establish the Northern institutions.

But at least they do so against a peaceful backdrop and in an Ireland in the throes of profound and incredible change.

Not the final chapter, but a new chapter.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)