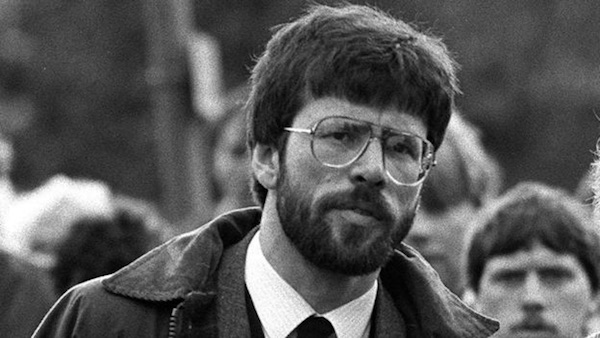

The Dublin government’s first intelligence on Sinn Fein’s peace initiative of 1987 claimed that Gerry Adams disapproved of some IRA actions and that the Sinn Fein leader saw the armed struggle as a “political liability”.

The party’s document of that year, ‘Scenario for Peace’, would become pivotal in the subsequent peace process. It outlined how a British declaration of intent to withdraw from the Six Counties could pave the way for an IRA ceasefire.

In a confidential report, dated February 4, 1987, officials in the 26 County Department of Foreign Affairs, said Bishop Cahal Daly had “picked up a rumour” that Mr Adams was trying to put together proposals which would enable the Provisional IRA to call a halt to their armed struggle.

According to Daly, Mr Adams had reached the view that the conflict was “getting nowhere, that it has become a political liability to Sinn Fein both North and South and that, as long as it continues there is little chance that he will be able to realise his own political ambitions.

“What he is believed to be working on is some form of ‘declaration of intent’ to withdraw, with however long a timescale, on the part of the British government.

“If he managed to negotiate something of this kind, the Provisional IRA would be able to lay down their arms without much loss of face, claiming that they had achieved the breakthrough towards which all their efforts had been directed.”

The file also contained a report on a meeting Mr Adams had with his Belfast lawyer, PJ McGrory.

McGrory told a Dublin government official that the Sinn Fein leader privately disapproved of individual IRA actions, but would never say so in public. He described Mr Adams as a “a politician more than a gunman”.

“[Adams] believes (or hopes) that the ‘movement’ will become more and more political as time goes by,” he said.

“Despite his professed subservience to the Army Council, the essential reality is ‘whatever Adams says, the Provos will eventually do’.”

McGrory added Mr Adams was looking for the British to give a timescale for withdrawal fromIreland “maybe 25, 40 or even 50 years” and if he found it acceptable he would be able to sell it to the IRA.

“It might take some time, and there would be a lot of suspicion and scepticism to overcome, but eventually he would carry the Army Council with him,” the lawyer was reported as saying.

The year 1987 was a pivotal one for the conflict, when Britain’s murderous shoot-to-kill operations began devastating ambushes of IRA Volunteers. Republicans were also polarised and weakened by the split in Sinn Fein, which led to the creation of Republican Sinn Fein, chiefly over the issue of political participation in the Dublin parliament.

Documents released from state archives for 1987 reflect rumours circulating at the time that the leadership of Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness were attempting to consolidate control of the Provisional republican movement by setting up some hardliners for attack. No evidence ever emerged to confirm the rumours, which have always been dismissed by Sinn Fein.

In particular, one priest told the Dublin government of a rumour that Gerry Adams helped to set up the Loughgall massacre of 1987, in which an IRA Active Service Unit was wiped out by British Army special forces. Eight members of the IRA’s East Tyrone Brigade were shot dead by the SAS, who were lying in wait, along with innocent bystander Anthony Hughes.

The rumour about Mr Adams was passed on to the Department of Foreign Affairs by Fr Denis Faul, a frequent critic of the Sinn Fein leadership, about three months after the massacre.

The priest, a school teacher and chaplain in Long Kesh prison who died in 2006, also claimed that two senior IRA figures who died Jim Lynagh and Padraig McKearney, were critics the Adams/McGuinness leadership and were leaning towards joining Republican Sinn Fein.

There is no record of the Dublin government’s response to the claim. A spokesman for Sinn Fein again said this week the suggestion was “utter nonsense”.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)