By Anna M. Hennessey (for Counterpunch)

People in the rest of the world, especially those from the 1980s onward, know little of Spain’s Civil War (1936-1939) and the long dictatorship that followed. This knowledge is helpful in understanding the situation in Spain and Catalonia right now.

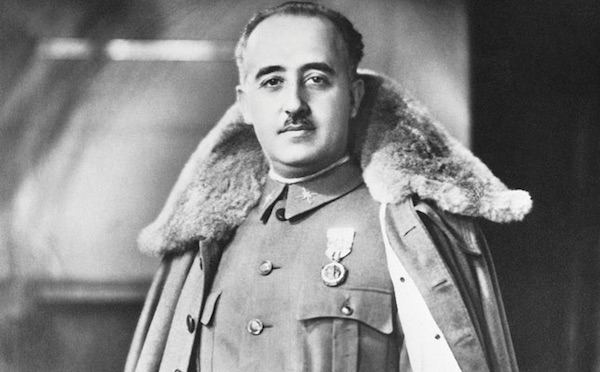

The judge (Ismael Moreno) tasked with deciding sedition charges against Catalan activists for attempting to hold a democratic referendum on October 1st, for example, has roots that are deeply connected to Francisco Franco (1892-1975), the military leader who initiated the Civil War, won it, and then went on to rule as Head of State and dictator in Spain for almost forty years.

Franco is a major figure of twentieth-century fascism in Europe. A purge of Francoist government officials never took place when the dictatorship ended in the 1970s, and this leadership has had a lasting impact on how Spain’s government makes its decisions about Catalonia, a region traumatised during and after the war due to its resistance to Franco’s regime. The lingering effects of Franco’s legacy are at this point well-documented and need to be a part of the discourse that surrounds what is quickly unraveling in Barcelona.

Over the past weeks, Spain’s military body, the Guardia Civil, has forcibly taken control of the Mossos d’Esquadra, Catalonia’s own police force. It detained government officials, closed multiple websites, and ordered seven hundred Catalan mayors to appear in court. Spanish police from all over the country traveled up to Barcelona, holing up in three giant cruise ships.

Like the Spanish government, the Spanish police force was never purged of its Francoist ties following the dictatorship. It is a deeply corrupt institution, a point revealed brilliantly in the recent documentary, Las Cloacas de Interior (The State’s Secret Cesspit), which includes numerous interviews with Spanish police, officials, and politicians who describe the corruption in detail. After a media blackout of the film in Spain this summer, the creators made it available through various online outlets.

Manuel Fraga Iribarne, one of Franco’s ministers during the dictatorship, founded Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s Popular Party. The party is currently enmeshed in a corruption scandal of its own. Spain’s royal family is similarly linked to Franco and has also been brought to trial for its own set of corruption charges.

It is impossible to ignore the fascist bedrock upon which modern Spain is founded, or to ignore the reality that this foundation has to do with the way Spain treats Catalonia. And yet we on the outside continue to make excuses for Spain, often conflating its problems with Catalonia to a squabble about taxes.

We have watched passively as arrests, police activity and other alarming developments build in Barcelona. We refer to the Spanish Constitution, which was written in 1978, as a way of backing up Spain’s dictatorial assertion that the Catalans have no right to self-determination and that the referendum is illegal.

The part of the Constitution that says Spain is indivisible was added not by the “fathers” of the Constitution, but by the military, as Jordi Soler Tura, one of two Catalan founders of the Constitution explained in 1985. Following the creation of the Spanish 1977 Amnesty Law, a law still active today, there has been no investigation or prosecution of the massive human rights violations that took place in Spain under Franco’s fascist dictatorship, and this was the same environment of suppression and authority in which the current Constitution was written.

After all the years of trauma that finally led into the tedious transition to democracy in the late 1970s following Franco’s death, many people in Spain and Catalonia are reticent to talk about these issues.

Franco died peacefully in his bed at age eighty-two after ruling over the country as dictator for almost half his life. Let’s imagine Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) dying peacefully in his bed sometime in 1971 following decades as Germany’s Nazi leader. We likely cannot imagine this scenario, but it is exactly what happened in Spain.

Franco and Hitler were both fascists who engaged in the mass murder of civilians for the purpose of “cleansing” their societies of those they believed to be of an inferior race or a threat. Franco in fact wrote the novel behind the movie, Raza (Race, 1941), which promoted the idea that hispanidad, or Spain’s superior race, comprised of those who were in line with Nationalist sentiment. The big difference between Franco and Hitler is that Franco won his war and Hitler lost his.

Most of us know about Hitler’s ethnic cleansing, the horrific extermination of Jews and others not in line with fascism. Under Franco, there were concentration camps in Spain too, and many Spanish political prisoners were sent abroad to Nazi camps in Germany and Austria, or ended up in internment camps in France. Paul Preston’s book, The Spanish Holocaust, shows how bad the situation was inside Spain. As Adam Hochschild writes in his 2012 New York Times review of the book, some atrocities included, “soldiers who flourished enemy ears and noses on their bayonets, the mass public executions carried out in bullrings or with band music and onlookers dancing in the victims’ blood...Franco’s troops practiced gang rape to frighten newly captured towns into submission...Tens of thousands of women had their heads shaved and were force-fed castor oil (a powerful laxative), then jeered as they were paraded through the streets soiling themselves.” The list goes on, mentioning the branding of women on their breasts and the shooting of pregnant women in a maternity hospital.

Thousands of the people who were tortured or sent to the camps were Catalans. During the years of Franco’s dictatorship, Catalonia was one of Spain’s strongholds of resistance, and the Catalan people suffered enormously for it. Following a military trial in 1940 that lasted less than an hour, Lluis Companys (1882-1940), the president of Catalonia’s Generalitat, or its system of governance, was tortured and then executed by the Guardia Civil. Companys is a symbol for what the Catalans endured during and after the Civil War. Many were murdered, disappeared, imprisoned, sent to concentration camps, had their children stolen, or were economically disenfranchised during these periods. Catalan people were also banned from speaking their language and saw other aspects of their culture suppressed by the fascist regime. Teaching and speaking of the language became legal only after Spain’s restoration to a democracy in 1978.

Rising above their past, the Catalan people have flourished in the twenty-first century and are the main contributor to Spain’s economy. Barcelona and the larger region are renowned for their industrious and creative workers. The Catalan language and its culture are thriving. The Catalans have a history of peaceful and communal resistance to the Spanish government, a tradition that continues today. The referendum that they seek is part of a basic democratic process, just as was the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence in the United Kingdom.

Franco was victorious and did not lose his war, as Hitler and Mussolini lost theirs, but this must not mean that we should let the dictator’s toxic ideological infrastructure persist any further into the twenty-first century. Supporting Catalonia is a necessary step in putting an end to fascism in Europe.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)