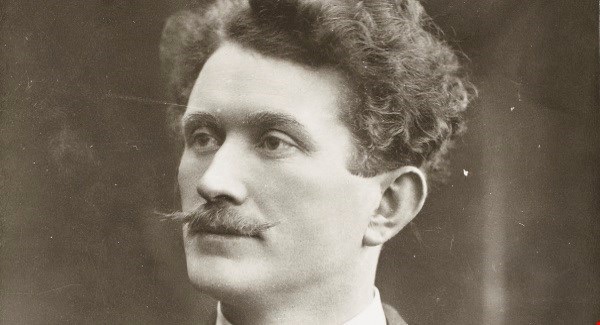

The following oration was delivered by Tommy McKearney, a former Hunger Striker, over the grave of Thomas Ashe at the national hunger strike commemoration of the 1916 Societies.

Tom Clarke spoke to us through his prison diaries saying that there is no weapon in the Imperial Arsenal capable of breaking the spirit of an Irish Republican who refuses to be broken. It was a significant statement repeated decades later by Bobby Sands and something that resonates from and with the life and sacrifice of the man we commemorate today, the heroic Thomas Ashe.

Had Thomas Ashe broken all connection with the struggle for a sovereign independent Irish republic after his release from imprisonment in Britain in June 1917, his name and fame would, nevertheless, still have lived in the annals of republican Ireland forever. His status and his standing would have echoed down the years for no other reason than the heroic battle he led against the British Empire in County Meath and North County Dublin during Easter week 1916. Alone, almost, outside the great city of Dublin, Ashe and his comrades engaged the British Empire during that historic week and did so with undeniable courage and incredible success.

With a battalion of just 48 men, his group successfully demolished the Great Northern Railway Bridge, disrupting the access of British reinforcements to the capital. In addition, they captured the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks at Ashbourne, County Meath. The battle lasted six hours, during which time 11 RIC men were killed and over 20 were wounded. Ashe and his men captured three other police barracks; quantities of arms and ammunition and in classic guerilla fashion maintained the struggle with arms captured from the enemy.

Yet it is not for this incredible story of military prowess and courage alone that we stand here today to pay tribute to the memory of Tom Ashe. It is to the awesome and indomitable spirit of the man that we bow our heads to here in admiration.

When England thought it safe and prudent to release the republican soldiers who had challenged its grip on Ireland in 1916, the empire must have felt that it had intimidated republican Ireland and crushed its will to resist. Those who ruled from London believed they had extinguished the flame that sparked the fight for freedom when they placed the leadership of the resistance before firing squads in the Stone-breakers yard in Kilmainham jail.

How well they must have thought that Ireland’s republican ideal would remain no more than a wish among the defeated.

It was not to be and no person made it clearer that this would not be the fate of that sacred cause than the heroic actions of Tom Ashe, the schoolteacher from Lispole in County Kerry. Elected to the presidency of the IRB, Tom Ashe immediately returned to serve the cause and only days after his release from imprisonment. Fearlessly he toured the country and fearlessly he preached the Fenian gospel of separatism, of independence and of the sovereign Irish Republic. And for asking for such basic entitlements he was arrested in July and sentenced under the draconian DORA (Defense Of the Realm Act) legislation for spreading disaffection.

In Mountjoy prison, he was subjected to treatment that has a chilling ring of familiarity even after all these years. In classic and vindictive fashion, the prison authorities began to curtail the Irish volunteers access to exercise. And in a classical response by imprisoned Irish republican, Ashe ordered the volunteers to break every rule in the jail and on 20th September 1917, he began a hunger strike. Five days later he was dead as a result of brutal and barbaric treatment as prison authorities inflicted fatal injuries while forcibly feeding him.

Hunger striking is not just the last and final weapon a prisoner has, it is also the most terrifying. It speaks of a commitment and a determination to prevail and to maintain that cannot be questioned or manipulated. It tells of an iron will that places the cause higher than life itself and that ultimately burns a message onto the wider narrative that says that there are those who cannot and will not be intimidated or diverted.

Tom Ashe’s life and heroic death told the immortal story to a generation and to generations that followed that the cause must not only be carried on but that it would be. That the spirit of Easter week had not perished with the executions. His sacrifice re-ignited the fires of freedom in the aftermath of Easter and gave fresh momentum to the renewed struggle.

A struggle that was to continue throughout the decades following his death. A struggle that was to be marked be equally glorious feats of courage and heroism. A struggle that was to be tragically and awesomely illuminate by the self-sacrifice of others who gave their all including their lives on hunger strike. Let us never forget that over a 64-year period of the 20th century, 22 Irish republicans have died on hunger strike and shamefully, several at the hands of governments in this state.

We remember today with pride the names of Tom Ashe and Terrence Mac Sweeney but we also remember with as much pride the memory and story of Jack MacNeela, Tony Darcy and Sean McCaughey. We keep sacred the memory of Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg as well as the ‘Gallant Ten’ who perished in the H-Blocks. Proof if it were needed that in the words of Fidel Castro, another who risked all for freedom and justice, when he spoke an eulogy for Che Guevara - you may kill the revolutionary but you can never kill the revolution.

And no cause that has such servants and has such servants honoured by the generations will ever be defeated. The unbending and unbreakable spirit coupled with the faith of the uncompromising in matters of principle that our hunger striking martyrs have displayed is our guarantee that we shall be free and independent in the Irish for which they and so many others have laid down their lives.

We shall speak the name of Thomas Ashe and the names of that other gallant 21 not just with pride but with undying gratitude for their sacrifice and for the contribution they have made to this Noblest of causes. We shall speak their names to fill us with confidence and with fortitude so that we may continue the struggle they have embellished and elevated.

We shall speak their names in an Irish republic, free and grand and when we too dare write Robert Emmet’s epitaph.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)