A big arms find in UDA’s Belfast HQ in 1981 proved embarrassing for a British government resisting calls to outlaw the group but trying to appear even-handed. An extract from ‘A State in Denial: The British Government and Loyalist Paramilitaries’ by Margaret Urwin.

In terms of the politics of proscription [of the UDA], we have always regarded the existence of such denials as more important than their accuracy. - C. Davenport, NIO official

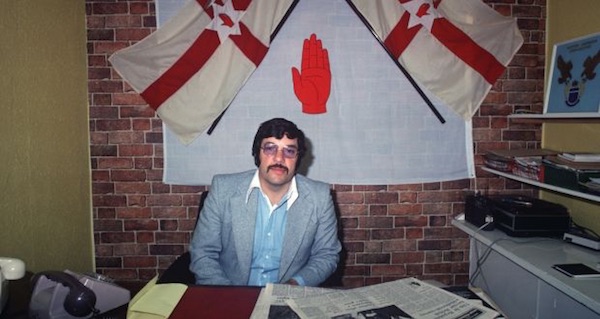

On 26 May 1981, at the height of tensions over the IRA/INLA hunger strike, the RUC searched the headquarters of the UDA in Newtownards Road, Belfast, and discovered the following weapons: one Thompson sub-machine gun, six home-made Sten guns, a .45 revolver and 550 rounds of ammunition. According to official records UDA man Robert McDevitt was arrested, while Andy Tyrie (pictured above) was merely interviewed. However, The Irish Times stated that two men were arrested along with Tyrie. The discovery prompted a debate amongst top civil servants, ministers and the chief constable. If involvement in outright sectarian murders was not sufficient cause to ban the UDA, would catching the organisation red-handed, with a deadly arms cache in its headquarters, be enough? Surely a Rubicon of sorts had been crossed?

This certainly triggered a flurry of internal memos between senior NIO officials. Assistant Secretary Stephen Boys-Smith, wrote to P. W. J. Buxton about the arms discovery, noting Buxton’s views at a meeting with the secretary of state the previous day regarding UDA proscription. Buxton had told Humphrey Atkins:

“The UDA is not now engaged in violence although it might be ready to resort to or encourage violence in extreme situations. The organisation reflects certain strands of the thinking of the Protestant community and it would be a substantial step to proscribe it.”

This statement was simply untrue. The UDA was, at that time, engaged in violence. In March, it killed Paul Blake, a Catholic, and - just ten days before the arms find - another Catholic, Patrick Martin. Buxton also ignored the high-profile attempted murder of the McAliskeys.

Some senior NIO officials had certainly been expecting an upsurge in UDA violence in response to the election of IRA hunger-striker Bobby Sands in the Fermanagh/south Tyrone by-election held on 9 April 1981. David Blatherwick had written to D. J. Wyatt in April stating that they were aware ‘that the UDA is currently considering a major escalation in violence as a response to Sands’ victory’.

At a meeting on 1 June Atkins expressed concern that the police had failed to make arrests following the discovery of the arms and had not sought extensions of detention while pursuing their enquiries. Justifiably, he worried that the police would not be seen to have acted as might have been expected had a similar discovery been made elsewhere, rather than at UDA headquarters.

In a note to John Blelloch, deputy secretary, NIO, dated 3 June, Buxton reported on his questioning of the chief constable, Sir John Hermon, the previous night about the failure to bring charges; he had put it to Hermon that he could have used Section 9 of the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1978 to do so.

Buxton had advised that Section 9 provided that when arms were found ‘in premises of which a person was the occupier and which he habitually used otherwise than as a member of the public’, that might be accepted as sufficient proof of illegal possession of arms, unless the person could prove ignorance. The section reversed the onus of proof - under Section 9 a person was not presumed innocent until proven guilty, but rather had to prove their innocence. Hermon had agreed that it had proven useful in other cases. In what appears to be a barely veiled criticism of the chief constable, Buxton advised Blelloch that ‘Hermon still needs to focus on the continued possibility of laying charges’.

It was a busy time for Buxton. In a long memo to the secretary of state’s private secretary, he discussed the arms discovery and echoed the secretary of state’s regrets that it was dealt with at divisional level without reference to RUC headquarters.

Either Andy Tyrie had very strong powers of persuasion, or the RUC regarded arms finds in the loyalist community very differently from arms finds in the republican community. After the local detective chief superintendent had taken him and the relevant UDA keyholders in for questioning, they had satisfied their interrogators they had no connection with or knowledge of the arms and were soon released without charge, including McDevitt. Buxton reported that the chief constable had conceded that it might have been ‘convenient’ to hold them for a couple of days, but, he added, the action taken, ‘professionally speaking’, was defensible. He explained that the UDA was a tenant of the property, not the owner, and the NIO had been unable to establish the status of other properties in which the UDA had an interest. He argued that if the UDA were proscribed, it would cause the organisation no difficulty to ‘declare themselves under another name’ and re-register properties under that name.

Buxton then presented the pros and cons of proscription. Points in favour were that statements by Andy Tyrie in recent months had come close to admissions of direct involvement in the ‘direction of terrorism’. In The Washington Star the previous week, Tyrie had defended assassinations and taken responsibility for ‘the small offensive unit called UFF’. The arms find at UDA headquarters lent tangible credence to these statements. Inaction by the government would put its credibility and that of the RUC at risk when they claimed an even-handed approach to law enforcement, he said. Proscription would please the Irish government and Irish-American circles and might act as a ‘sweetener’ to the ‘beleaguered Catholic community’.

The points against proscription were that Tyrie had played a ‘generally helpful’ role in stabilising loyalist opinion. If the UDA were to be proscribed, he would lose control, creating a ‘second front’ for the security forces when they were fully stretched on the main front, combatting the IRA. They could expect disturbances in Protestant areas, just when the marching season was beginning; the conviction of UDA wrongdoers would be more difficult, given the ‘general disaffection’ and drying up of intelligence sources. It would alienate the ‘Protestant community’, even those who had no sympathy with the UDA; the organisation had just unveiled some worthy plans for a new political movement - proscription would probably nip that in the bud.

Buxton imparted the views of Hermon, who he said was firmly of the view that this was an inopportune time to proscribe the UDA. In Hermon’s view, two conditions would have to be satisfied - the politico-security scene must be quiet (meaning that the hunger strike crisis must be past), and the UDA should have developed politically to a point ‘where the mass of dormant membership and the “social welfare/community worker” elements had been syphoned off, leaving a rump of hard men (loosely speaking the UFF) and an ordinary criminal fringe ripe for proscription’.

The chief constable had warned Buxton that, if the government decided to proceed with proscription, it could not count upon his support, and he hoped to be given the chance to state his views before a final decision was taken, preferably at a meeting with the secretary of state. Although not quite a veto, this does seem to be the chief constable exerting an undue influence on government policy. If ministers decided not to proscribe for the moment, Hermon would be glad to be quoted in support of the decision. His chief argument was the ‘demonstrable efforts of the RUC to bring members of the UDA to book and the obstacles which proscription would place in their way in the future’.

Buxton agreed that a strong argument could be advanced about the prosecution of UDA members and suggested it was proof of the RUC’s bona fides in claiming an even-handed approach and no sanctuary for the UDA. He suggested that, in security terms, proscription would be counterproductive and politically would tend to aggravate rather than ease intercommunal tensions and provoke demands for similar action, which they would be very reluctant to take at present, against ‘supposedly similar’ republican organisations. He concluded by recommending that the secretary of state should not proscribe the UDA but should keep the matter under close review, agreeing with Hermon that if Atkins felt unable to accept his recommendation, he should invite the chief constable to present his case before a final decision was made.

Boys-Smith, in a most revealing memo, wrote to Blelloch on 5 June, reminding him of a remark by Atkins that proscription would ‘deprive the security forces of the access which they presently had to those members of the UDA who were also active in terrorism’.

As can be seen from the de Silva report into the murder of Pat Finucane, around 85 per cent of all UDA intelligence information was coming from the various branches of the British security forces at this time. Clearly the ‘access’ worked in both directions, and to the UDA’s benefit. According to a BBC Panorama programme, Lord Stevens, during his investigations, arrested 210 loyalist paramilitary suspects, of whom 207 were agents or informants for the state.

A document included in de Silva’s report, headed ‘Collusion between the security forces and loyalist paramilitaries’, observes that the flow of intelligence to the UDA increased significantly around the time of the Anglo-Irish Agreement: ‘However, it is assessed that research of intelligence dating from previous years would be likely to reveal a similar picture to that given in the attached document.’ Boys-Smith appreciated that proscription would alienate sections of the ‘Protestant community’ and agreed that it ‘would not be right at present to proscribe the UDA’, although he noted that Atkins had again expressed concern at how the discovery of arms at UDA headquarters and the associated police action would be interpreted, especially if the UDA was not proscribed. ‘He feared the Government and police would not appear impartial, and that, even if there were good grounds for not bringing prosecutions, they were not ones which would necessarily be understood in the Catholic community or generally in Great Britain or elsewhere.’

The chief constable, he advised, had called on the secretary of state later that day. Atkins remarked that Hermon was opposed to proscription ‘at this stage’ as he ‘thought it would be unhelpful to the preservation of security’. He accepted the chief constable’s advice but told Hermon he was ‘concerned about the perception of events’, both in terms of the discovery of arms and the subsequent arrests and about the continuing police investigation. Boys-Smith commented that the secretary of state had to be mindful of ‘the questions which would be asked of him in Parliament and by his colleagues and others in Great Britain’. While he was ready to answer the suggestion that the UDA should be proscribed ‘because of the misdeeds of a few of its members’ and he had up to then believed he could do so effectively, the discovery of arms created ‘a different situation’. The UDA as a whole was seen to be involved, and Atkins worried that ‘questions about its future were bound to be raised’. Many people would assume that the UDA’s ‘Chairman’ (Tyrie) and other officers could be held responsible; ‘this might be the case particularly with those who knew of Section 9 of the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1978’.

Boys-Smith observed that Atkins had suggested the criticism would be muted if there were arrests and prosecutions. He appreciated that prosecutions were only possible if there was a reasonable chance of conviction, but believed ‘a legitimate prosecution which failed in the courts might be better than no prosecution at all’. He stressed to Hermon the sensitivity of the situation and the importance of taking action which would minimise the harmful reaction.

The chief constable reiterated that he did not believe UDA proscription at the present time was the right way to go and asserted:

“Most UDA members did not act illegally and the organisation was not active in violence. Only a small core of its members was involved in terrorism or illegal activities and they were not a sufficient reason for proscription. There was a good record of success against Protestant extremists which would be hindered rather than helped by proscription.”

Hermon conceded that ‘the immediate aftermath of the discovery of arms had been badly handled by his officers’ - the release of the three suspects ‘had been premature, given the context in which the arrests had been made, and the decision had not been referred to a suitably senior level in the Force ... He did not believe that charges could be brought against the officers of the UDA’, notwithstanding Section 9 of the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act and was opposed to prosecutions that would result in acquittals. He had assured Atkins that enquiries ‘were being pursued urgently and energetically’ to try to identify those who might be involved and to arrest and detain them for questioning.

While politicians such as Atkins might have claimed ignorance of the true nature of the UDA, no such excuse was available to Hermon. As chief constable, he had full access to Special Branch intelligence and would have been well aware of the widespread involvement of the UDA in assassinations, bombings, extortion and intimidation.

In the month before the arms find, NIO official D. F. E. (Frances) Elliot drafted a letter to a Mr McNamara of Liverpool in answer to his letter requesting the proscription of the UDA, dated 25 March. Ms Elliot explained that the secretary of state was not, at present, going to proscribe the UDA. She wrote that the decision was based:

“on the difference between an organisation as such being engaged in terrorist activities (as for example, the PIRA or the UFF, both of which are proscribed) and individuals (who also happen to be members of an organisation) committing crimes.”

This oft-repeated disingenuous and subtle distinction was based on two false premises. First, the UFF was not a separate organisation but merely a cover name for the UDA. Second, it assumes that ‘individuals’ who carried out acts of terror were acting alone and were not being directed by leaders of the UDA.

Michael Canavan of the SDLP persisted in his efforts to have the UDA proscribed. On 1 June he wrote again to the secretary of state with new information to bolster his case, referring to seventeen members of the UDA convicted of terrorist offences; an Ulster Television Counterpoint programme detailing UDA gun-running from Scotland; the judicial comments, not only of Justice Murray at the trial of the killer of Alexander Reid, but also of Justice McDermott (3 April), Justice Rowland (18 April) and Justice Doyle (24 March and 28 May); and armed attacks on at least five persons, one fatal.

Having taken the decision not to proscribe the organisation, officials struggled to decide whether or not to inform Canavan of this. In a remarkably cavalier response to Canavan’s dogged and justifiable concern, C. Davenport of the Law and Order Division of the NIO advised against informing him, noting that ‘interest in the UDA has gone off the boil’.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)