The Sack of Cashel (also known as the Massacre of Cashel) was a notorious atrocity which occurred in County Tipperary in the year 1647.

The town of Cashel was held by the Irish Catholic Confederate’s Munster army and was besieged and taken by an English Protestant Parliamentarian army under the Baron of Inchiquin, Murrough O’Brien. The attack and subsequent sack of Cashel was one of the more brutal incidents of the wars of the 1640s in Ireland.

In 1642, most of the province of Munster was under the control of Irish Catholic forces with the exception of Cork city and a few towns along the south coast, which were in the hands of Protestant, largely English settlers. Since then, the province had been fought over by the Catholics, organised in the Catholic Confederation, and the Protestants, led by the Earl of Inchiquin.

The political and military situation was further fragmented by the English Civil War, in which the Catholics gave their support to King Charles I, and the Protestants, since 1643, to the English Parliament. What was more, the Confederate Catholics were themselves split over the terms on which they should sign a peace deal with the King. A deep rift developed within their ranks in 1647 between those who were prepared to accept a mere toleration of Catholicism in return for an alliance with the English Royalists and those who in effect wanted Ireland to be Catholic kingdom, albeit under sovereignty of the Stuart monarchy. This infighting was to fatally hamper the war effort of the Confederates in Munster and make possible the Protestant sack of Cashel.

In the summer of 1647 the Baron of Inchiquin, the Irish Protestant commander of the Protestant army of Cork, commenced a campaign against the Irish Catholic strongholds in Munster. The counties of Limerick and Clare were raided and he soon turned his attention to the bountiful eastern counties of Munster. In early September, his forces quickly took the Castle of Cahir in Tipperary. This strong castle was well positioned to become a base for the Cork Protestant army, and it was used to raid and devastate the surrounding countryside.

Inchiquin had already launched two minor raids against Cashel, but the Irish defenders were unprepared for a major assault. The Parliamentarian forces first stormed nearby Roche Castle, putting fifty warders to the sword. This attack terrified the local inhabitants of the region, some of whom fled to hiding places, while hundreds of others fled promptly to the Rock of Cashel, a stronger place than the town itself.

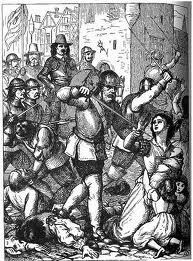

Arriving with his army at the Rock, Inchiquin called for surrender within an hour. The defenders of the churchyard offered to negotiate, but that was refused, and on the afternoon of the 15th of September the assault commenced. The attack was led by around 150 dismounted horse officers (who wore more armour than the foot) with the remainder of the infantry following; troops of horse rode along the flanks of the advancing force to encourage the infantry. The Irish soldiers attempted to drive off the attackers with pikes while the civilians inside hurled rocks down from the walls: in turn the attackers hurled firebrands into the compound, setting some of the buildings inside on fire. Although many were wounded, the Parliamentarians gradually fought their way over the walls, pushing the garrison into the church.

Initially, the Irish defenders managed to protect the Church, holding off the attackers trying to get through the doors, but the Parliamentarians then placed numerous ladders against the many windows in the church and swarmed the building. For another half an hour fighting raged inside the church, until the depleted defenders retreated up the bell tower. Only sixty soldiers of the garrison remained at this point, and they thus accepted a call to surrender. However, after they had descended the tower and thrown their swords away, all were killed.

In the end all the soldiers and most of the civilians on the Rock were killed by the attackers. The Bishop and Mayor of Cashel along with a few others survived by taking shelter in a secret hiding place. Apart from these a few women were spared, after being stripped of their clothes, and a small number of wealthy civilians were taken prisoner, but these were the exceptions. Overall, close to 1,000 were killed, amongst them catholic scholar Theobald Stapleton. The bodies in the churchyard were described by a witness as being five or six deep.

The slaughter was followed by extensive plunder. There was much of value inside, for apart from pictures, chalices and vestments of the church, many of the slain civilians had also brought their valuables with them. The sword and mace of the mayor of Cashel, as well as the coach of the bishop were captured. The plunder was accompanied by acts of iconoclasm, with statues smashed and pictures defaced. The deserted town of Cashel was also torched.

The atrocity at Cashel caused a deep impact in Ireland, as it was the worst single atrocity committed in Ireland since the start of fighting in 1641 and took place at one of the chief holy places of Ireland. The slaughter of the garrison at Cashel and the subsequent devastation of Catholic held Munster earned Inchiquin the Irish nickname, Murchadh na Dóiteáin or “Murrough of the Burnings”.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)