Monaghan Republican and Ex-PoW John Crawley with a graveside oration at the Easter Commemoration for ‘The Bold McElwain’ in Scotstown ahead of his 30th anniversary commemoration.

Unlike many here today I didn’t have the privilege of knowing Seamus McElwain personally. I found out only in the last fortnight that he and I were members of the same Colour Party in 1980 but with all the activity on the day I don’t believe we had the opportunity to speak to each other. I do recall the first time I heard tell of Seamus. I was in a house at another part of the Border and a Volunteer from this end of the country told me about a young lad who showed particular promise and was shaping up to be an outstanding IRA Volunteer. I looked forward to meeting him but between prison sentences and one thing or another I kept missing him.

I was in Portlaoise prison in April 1986, serving the first of three sentences when news came through that Seamus had been killed in action. Jim Lynagh had been released from Portlaoise prison only a week previously. Little did Jim know that he would shortly be attending the funeral of his friend and comrade Seamus McElwain or that his own funeral lay so close ahead, just over a year later, along with seven of his comrades killed at Loughgall. That was the dangerous world IRA Volunteers inhabited in 1986 when Seamus lost his life.

Few of us knew then what was ahead of us but all of us knew what we were fighting for and let nobody tell you different. We were on precisely the same mission as the men and women of 1916 - to put an end to British Crown sovereignty in Ireland and to establish a 32-county republican government of national unity based upon democracy and social justice. To that end we were prepared to engage in both military and political activity.

Militarily Seamus was a legend. A highly motivated, courageous and inspiring Volunteer, he placed himself continually at the tip of the spear, at the cutting edge of resistance, leading from the front, leading by example. In any conventional army Seamus would have been a highly decorated soldier, recognised and acclaimed for his audacity and gallantry. But in the secretive and perilous existence of an IRA Volunteer, involved in a guerrilla campaign against such overwhelming odds, his exploits would, for the most part, and of necessity, remain known only to a select few. Such courage and commitment cannot, however, be kept completely secret in all its aspects and his reputation grew and spread among his comrades in the IRA and among the many supporters of the republican struggle who, at great sacrifice and personal risk, opened their homes to Seamus and his comrades.

In addition to his military activities Seamus was also active politically. His father James was a member of Monaghan County Council for 20 years and Seamus himself had run in a 26-county general election in 1982, while on remand in Crumlin Road prison, receiving an impressive vote.

In 1986, political activity was encouraged by most thinking Volunteers. The IRA campaign could not be allowed to become a spectator sport, with a small number of Volunteers taking all the risks to life, limb and liberty. We needed to make ourselves relevant to people’s lives and build alliances both foreign and domestic. A larger portion of the populace had to become involved in the republican struggle, had to be educated in the necessity of Irish Unity and independence and had to become an integral and engaged part of what we believed would be the final stage in Ireland’s long War of Independence.

Make no mistake that when Seamus was killed in 1986 republican politics, for the Active Service Units in the field and for the captured Volunteers in the prisons, was about furthering the aims, ideals and objectives of the 1916 Proclamation. Political opportunism and careerism was, in our view, strictly reserved for Castle Catholics and partitionist poltroons.

The British government, for their part, took us on militarily and politically. When you take on the Brits you are taking on a lot, utterly ruthless they are world-renowned experts in counter-insurgency. According to one British historian, of 196 countries in the world today the British have invaded or established a military presence in 171 of them. So it is not surprising that they have evolved a multi-layered and coordinated approach to achieving British strategic objectives through the focused use of applied violence and the manipulation and co-option of indigenous leaderships, groups and movements.

Militarily they used their informer directed SAS ambush teams to kill IRA Volunteers in direct combat. Behind the scenes they used Loyalist death squads, armed and directed by RUC Special Branch and British Military Intelligence, to murder republicans, their supporters and totally innocent Catholics whenever they judged it opportune to do so. Their agents bombed Dublin and Monaghan and carried out a host of other black operations, North and South and overseas. They killed who they could, they jailed who they could and they bought who they could.

In parallel with their military efforts the British had a political strategy. They outlined this very clearly in a discussion paper produced after the so-called Darlington Conference in September 1972. In this paper the British government published what it called ‘some unalterable facts about the situation’ and ‘some fundamental conditions... which any settlement must meet’.

These included UK parliamentary sovereignty over all persons, matters and things within the Six Counties, All-Ireland endorsement of the Unionist Veto, the need for a reformed Stormont giving Nationalists a share in the exercise of executive power, public confidence in, and collaboration with, the locally-recruited British constabulary, and the need for Dublin government buy-in to the new arrangements, with a special focus on the removal of Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Constitution and increased security collaboration with the 26-county state.

In a separate strategy, the Brits also hoped to lure republicans into protracted and ambiguous negotiations, in order to gain intelligence and gradually ensnare them into a habit of interfacing with agents and agencies of the UK government as part of a British state legitimation process. Softly, softly catchy monkey.

So British policy, from the very beginning of the Troubles, was to dismantle the Orange state and replace it with a viable political entity which would preserve the political and territorial integrity of the United Kingdom. To do this the British needed to defeat or neutralise the IRA and bring the vast bulk of nationalists on board as stakeholders in a reformed Stormont. As their strategy evolved, they realised they needed to do more to convince unionists that these moves did not flag up any disengagement from Ireland. The Downing Street Declaration of 1993, which outlined British preconditions for a settlement, refers to the Unionist Veto eight times in its twelve points.

The British can be quite practical. If you oppose the British state in what they consider the wrong way they may imprison or kill you. But the British will pay you a salary and expenses to oppose them if you agree to become bound by their terms and conditions. When British Prime Minister Tony Blair announced the train was leaving the station and any party not on it would be left behind he didn’t mean the freedom train to a United Ireland but the gravy train to Stormont.

A constant battle was fought between republicans who wanted politics to be about revolutionary advancement and British counter-insurgency strategists who were trying, through the judicious use of bribery and butchery, to nurture a loyal nationalist opposition and an insurgent leadership fit for purpose.

What was that purpose? To shape the strategic environment in a way that allowed Britain to define the nature of the conflict, shape the parameters of Irish democracy and determine the boundaries within which Irish opposition to British rule must operate. For Republicans, democracy in Ireland is the expression of a united and free people, fully informed and without outside interference or impediment. For the British, democracy in Ireland is any mechanistic exhibition of electoral theatre which, despite the use or threat of force, bribery, censorship, partition, gerrymander or sectarian interventions, achieves a desired result.

At present there is no mechanism to advance Irish Unity that isn’t comprehensively ringfenced by British constitutional constraints. A glaring example is the proposed six-county Border Poll under Britain’s Northern Ireland Act 1998, which permits the Secretary of State (presently an English politician without a single vote in Ireland) to determine if and when a poll may be called, the wording of the poll and who qualifies to vote. Even if passed, the British parliament retains the final say on whether or not the result will be endorsed by the UK government.

The British have a remarkable capacity for channelling Irish political trajectories in a particular direction, harnessing Irish leaderships to drive the strategy and then making the Irish believe it was their own idea. James Connolly called it ‘ruling by fooling’.

A core concept of Irish republicanism is that Irish constitutional authority derives exclusively from the Irish people and does not defer to laws or decrees emanating from England. The signatories to The Proclamation believed that in April 1916, every republican believed that in April 1986 and, despite all the inducements to do otherwise, many of us believe it still.

We are told by the political establishment north and south that the 1998 Good Friday Agreement represents the democratic will of the Irish people. We were once told that the achievement of Home Rule represented the democratic will of the Irish people. Then we were told that the 1918 General Election was the democratic will of the Irish people. Then the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty was the democratic will, except this time the only democratic will that mattered was that of the Irish people in the 26-Counties. And so it goes ad nauseum.

A Fine Gael TD and former Dublin government minister claimed that the results of the 1998 referenda on the Good Friday Agreement were, ‘the purest form of self-determination ever given by the Irish people’. Yet in 2000 and again in 2002 British Colonial Secretaries, who between them had never received as much as a single vote in the whole of Ireland, were able to scrap the Good Friday institutions and reinstate British direct rule. So much for the democratic will of the Irish people, dismissed with the stroke of an English pen. Under the principle of UK parliamentary sovereignty the British government can do this at any time it chooses without reference to a single member of the Irish electorate. The Brits are able to do this because in Stormont Irishmen and women hold office but England holds power.

We are often advised we must not dissent from a political process which bestows upon Britain democratic title in Ireland because it could undermine the peace. Liam Mellows TD said during the Treaty Debates in 1921, ‘if peace was the only object why, I say, was this fight ever started? Why did we ever negotiate for what we are now told is impossible? Why should men have ever been led on the road they travelled if peace was the only object? We could have had peace, and could have been peaceful in Ireland a long time ago if we were prepared to give up the ideal for which we fought.’ Liam Mellows was later executed by the Free State government for defending the Republic and resisting British attempts to impose a treaty which partitioned Ireland and re-defined Irish democracy in British Imperial interests.

Being an authentic and active republican has often been a serious and dangerous business. We know from Irish history what a soft bed can be made from a tissue of lies. There have always been those who service the lie at great personal profit and those who act on the truth at great personal cost.

Seamus McElwain died acting on the truth. The same truth spoken by James Connolly at his court martial 100 years ago when he said, ‘we went out to break the connection between this country and the British Empire, and to establish an Irish Republic... Believing that the British Government has no right in Ireland, never had any right in Ireland, and never can have any right in Ireland, the presence, in any one generation of Irishmen, of even a respectable minority, ready to die to affirm that truth, makes that Government for ever a usurpation and a crime against human progress.’

Breaking the British connection was what the struggle for Irish freedom was about in 1916. That is what the struggle for Irish freedom was about in 1986, when Seamus died for it, and that is what the struggle for freedom is about now. In the words of Padraig Pearse, ‘we know only one definition of freedom: it is Tone’s definition, it is Mitchel’s definition, it is Rossa’s definition. Let no man blaspheme the cause that the dead generations of Ireland served by giving it any other name and definition than their name and their definition.’ Although some former comrades now call on us to respect the British connection as a gesture to Irish Unionism, breaking that connection and establishing a united national citizenship free from Britain is the historic mission of Irish republicanism.

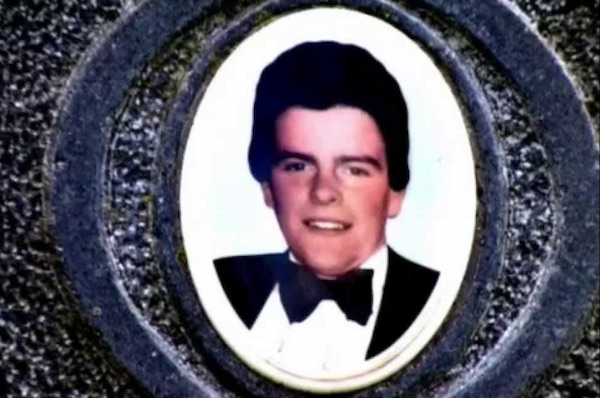

Seamus McElwain was a good republican, a good soldier and a good man. His death at the hands of the British army of occupation near Roslea, Co. Fermanagh on the 26th of April 1986 was an incalculable loss to his family, his friends and his comrades. His life is remembered by them with love and pride. To those who did not know Seamus personally, or were not even born when he was killed on Active Service, his truth, courage, honour and commitment are an inspiration and an ideal to be aspired to. Fuair se bhas ar son Saoirse na hEireann.

* Monaghan Republicans, in conjunction with the McElwain family, are holding an Independent 30th Anniversary Commemoration to Vol. Seamus McElwain at the Monument in Knockatallon, Saturday 23rd April at 2pm. All welcome.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)