By An Sionnach Fionn

In the final hours of the Easter Rising of 1916, from the evening of Friday the 28th of April to the morning of Saturday the 29th, soldiers of the British Army’s South Staffordshire Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Taylor, inflicted a terrible revenge for the would-be revolution on the civilian population of North King Street, a working-class district to the north-east of Dublin’s main thoroughfares.

Despite their overwhelming numbers, firepower and the use of improvised armoured cars the United Kingdom’s forces had been thwarted in the area by a handful of units attached to the Four Courts Garrison of the Irish Republican Army led by Commandant Edward Daly, advancing no further than 140 meters into the insurgents’ lines after three days of fighting. Seizing civilian hostages in the warren of narrow streets, tenement houses and small businesses that characterized that part of the capital, from 6pm to 10am the troops proceeded to murder at least seventeen men and boys, wounding several others, while stealing from both the corpses and their homes in scenes of general looting. Most of the killings took place in a small block of just nine buildings.

At the address of No. 170 North King Street, a disused, partly ruinous building, Thomas Hickey (age 38), his son Christopher Hickey (age 16) and neighbour Peter Connolly (age 39) were beaten, bayoneted and shot to death, their bodies buried in the back yard of the house. The three had been taken from No. 168, the shop owned by the Hickey family at the corner of Beresford Street, and brought two houses up to be tortured and murdered out of sight or earshot of witnesses. At No. 177, Mary O’Rourke’s public house, the foreman Patrick Bealen (30) and James Healy (44), a clerk at Jameson’s Distillery on Bow Street, were shot multiple times, their bodies buried in a shallow pit in the basement; before his death Paddy had made tea for his soon-to-be military killers. In No. 174, a local shop, Michael Nunan (34), a sales-assistant and brother of the owner, and George Ennis (51), a carriage body maker at Moore’s Factory, were tortured with bayonets and shot; the bloodied Ennis managed to crawl back to his wife, Kate, and died in her arms twenty minutes later. At No. 91 Edward Dunne (43), a general labourer, was beaten and executed, leaving behind his wife Jane and at least one daughter. At No. 172, another small shop, owner Michael Hughes (50) and John Walsh (34), a neighbouring cattle drover and former soldier who sought refuge in the address along with his family, were also gunned down; their murders were witnessed by their families. Michael and Sally Hughes had opened their business just two days before the insurrection and the building was still half empty.

In No. 27 North King Street, the premises of the “Louth Dairy”, Peter J Lawless (21), the son of the owner and a citizen of the United States, James “Jim” McCarthy (36), manager of Gallagher’s Tobacco Store in Dame Street, James Finnegan (40) and Patrick Hoey (25), both bread-car drivers and tenants in the building, were beaten and their throats slit; their partially scorched corpses were buried by soldiers overnight in the rear yard of the business. On nearby Coleraine Street John Biernes (50), who worked at Monk’s Bakery on the corner of North King Street and Upper Church Street, was shot dead by a British sniper, while William O’Neill (the young brother-in-law of the murdered John Walsh above) was killed by the same marksman when he and a second man went to retrieve Biernes’ body some time later. On Constitution Hill James Moore was shot dead by passing troops as he stood on his doorstep in Little Britain Street, again almost certainly by soldiers belonging to the rampaging contingents from the 2/6th Battalion TF South Staffordshire Regiment.

Despite the outrage that greeted the discovery of the slaughter following the end of the insurrection no member of the British Army was ever brought to book for his hand or part in the murders. On the contrary the UK authorities rallied around the killers, defending their actions as wholly justified. In the words of General Sir John Grenfell Maxwell, leader of the Imperial Forces in Ireland:

“We tried hard to get the women and children to leave North King Street. They would not go, their sympathies were with the rebels.”

Which simply gave further support to the order issued during the fighting by Brigadier-General William Lowe, the UK commander in Dublin, that known or suspected “rebels” were not to be taken prisoner.

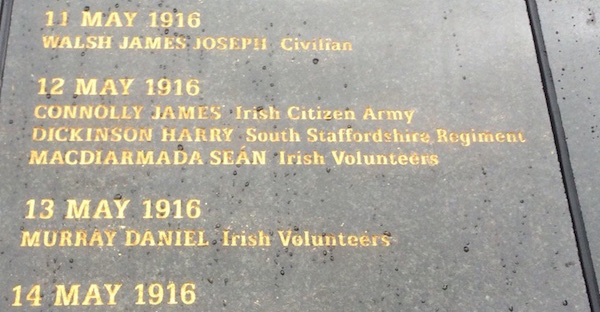

Incredibly the modern state of Ireland has now paid tribute to perpetrators of the North King Street Massacre, to the murderers of Irish men and boys, by adding their names to the newly erected Glasnevin 1916 Remembrance Wall, a monument inscribed with the names of all those who died during the Easter Rising. Alongside sixteen year old Christopher Hickey and twenty-one year old Peter J Lawless sits the names of the men who were their killers or the accomplices of their killers. Far from a Remembrance Wall it has become a Wall of Shame, a dishonouring of the dead.

Names of British Army killers honoured on Glasnevin’s 1916 Rememberance Wall alongside those they killed Names of British Army killers honoured on Glasnevin’s 1916 Rememberance Wall alongside those they killed One such name from the so-called 1916 Remembrance Wall is that of Harry Dickinson, a member of the infamous South Staffordshire Regiment, who died of wounds on the 12th of May 1916, probably received while fighting in the North King Street area, site of the massacre. The unfortunate Dickinson is buried in the Grangegorman Military Cemetery, a former UK graveyard near the Phoenix Park in Dublin, and his name is already inscribed on its Wall of Remembrance. With the support of the Royal British Legion and the government of Britain, and regarded by them as a “Fallen Hero”, Harry Dickinson will now receive greater recognition than the citizens of Ireland he and his fellow soldiers murdered. Meanwhile several of those who died in North King Street were, until recently, buried in unmarked graves at Dean’s Grange Cemetery.

The misspelled Glasnevin 1916 Remembrance Wall The misspelled Glasnevin 1916 Remembrance Wall To add insult to injury, and to illustrate even further the facile Irishness of the political establishment on this island nation, which fears even the memory of the 1916 revolution, the Irish text on the Glasnevin monument is misspelled. Eiri amach “rising out” becomes Eiri amach, which has no meaning at all. Much like the official celebrations of the Easter Rising, in fact.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)