By Colette Browne (for the Irish Independent)

Two years ago, Taoiseach Enda Kenny spoke of a seismic shift in EU policy which would finally separate banking debt and sovereign debt. Today, that seismic shift has been long forgotten - and the government’s spin merchants are instead peddling some new snake oil.

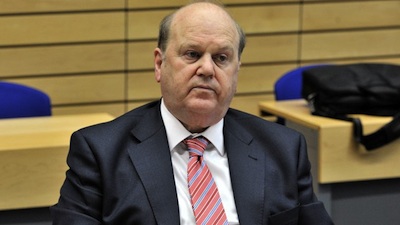

Finance Minister Michael Noonan is being lauded as some kind of conquering hero for convincing the IMF to allow us to repay them 18bn euro early.

You see, when the IMF bailed the country out it attached a hefty interest rate to the repayments.

The minister plans to take advantage of Ireland’s low borrowing costs on private markets to repay this money and save between 300m and 400m euro a year.

This has all been agreed with the IMF, but there’s a snag. Noonan needs to get permission from our chums in the EU and the ECB for the deal to go ahead.

The deal won’t actually cost them anything, or affect them in any material way, yet we still have to go crawling and begging for their permission.

So, for the last week breathless reports from financial journalists have been detailing the allegedly tense negotiations that are under way in order for the deal to get the green light.

If it does go ahead the minister - by all accounts - will be in line for a canonisation, with economist Stephen Kinsella writing that “he will have sealed his place in history”.

Which begs the question, has everybody lost their minds? Or is the country just suffering from a particularly acute case of amnesia.

If so, allow me to remind you of some painful facts and figures that no one in government is too eager to trumpet.

According to Eurostat, Ireland, which comprises less than 1 per cent of Europe’s population, shouldered 43 per cent of the net cost of the banking crisis across all 27 EU member states - 41bn euro out of 96.2bn.

As a percentage of GDP, that figure amounts to a staggering 25.8 per cent for Ireland. To put that into perspective, the next highest percentage is 3.3 per cent for Latvia.

It means that the cost of the bank bailout was 8,956 euro for every man, woman and child in Ireland, compared to an EU average of 191 euro.

It gets worse. The 41bn euro figure cited by Eurostat doesn’t take into account the 20.7bn euro from the National Pension Reserve Fund that was used to bail out banks, because that figure wasn’t added to the national debt.

In total, about 64bn euro was shovelled into the bloated corpses of Irish banks, around 40 per cent of GDP.

The figures are so scarifying that they prompted one TD, during a debate on the terms of the bailout in December 2010, to thunder: “What legal or moral compulsion is on Ireland to honour in full debt incurred by Irish banks when there was no State involvement?

“It is obscene that liability for these loans is now being transferred to the Irish taxpayer, in many respects to the poorest of the Irish taxpayers.”

That TD was Michael Noonan, who rapidly jettisoned any of his previous concerns about the morality of foisting tens of billions of banking debt onto the shoulders of Irish people as soon as he entered Cabinet.

Instead, the best we can now hope for, according to those at the negotiating table, is for the terms of the troika loans to be tweaked and made marginally better.

The net result is akin to telling a prisoner that his life sentence has not been commuted, but that he is about to be transferred to a nicer cell.

We have become so inured to intransigence on the issue that a potential saving of up to 400m euro is being touted as a miraculous achievement when the cost of servicing the banking debt this year alone is 1.6bn euro.

Meanwhile, if this IMF deal does go ahead, it is likely that it will be presented as some kind of benevolent gesture on the part of the EU, which will promptly put the kibosh on any prospect of Ireland’s banks being retrospectively recapitalised.

The government is adamant that recapitalisation is still on the cards, but they seem to be the only ones who think this is still a feasible option.

In July, a senior German politician bluntly said Ireland had “no chance” of securing money via the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in November.

Instead, Ireland is the cautionary tale that prompted the setting up of the ESM, which will mean Eurozone banks will no longer be bailed out by taxpayers but by banks and bondholders.

Establishing the ESM was done while Ireland held the presidency of the EU, but we will be precluded from availing of it because we have already repaid all of the bondholders in full. Instead of being rewarded with cold, hard cash, our EU partners expect that we will be satisfied with their patronising pats on the head and the warm glow that comes from knowing our sacrifice saved the EU’s banking system.

Irish politicians, the people who are supposed to represent our interests and fight our corner, appear happy to collude in this charade and roll over.

If this is the best deal the Irish government can get, then it is not a victory. It is a failure.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)