Those who left behind poverty in Ireland only to become involved in America’s internal conflict should also be remembered. A historical article by Eddie Hobbs.

Last weekend, 150 years ago, Union General William T Sherman began his encirclement of Atlanta. The capture of the commercial capital of the Confederacy on September 2, 1864, led directly to the re-election of Abraham Lincoln and shaped modern history.

Facing Sherman was Confederate General John Bell Hood, who Jefferson Davis, the Richmond-based president of the Confederacy, had chosen as his new western commander. He should have chosen Corkman Major General Patrick Roynane Cleburne. Much like many of the estimated 170,000 Irishmen who fought in the US Civil War, Cleburne is largely forgotten, despite reaching the highest military rank for a non-native-born officer. Hood would destroy his army in a series of suicidal assaults at Franklin in Tennesseee three months later, leading to the death of the 36-year-old Ovens man, by some stretch, the Confederate’s most aggressive and effective commander in the western theatre.

The Corkman had caused consternation in the South the previous year by advocating the freeing and arming of slaves to fight for it. Cleburne had merely spoken the truth - but he was no politician - if the “negro” proved equally as efficient at soldiering as the white man, then the whole basis upon which the war was being fought by the South would be grievously undermined.

The green flags in the Union army, in which an estimated 144,000 Irishmen enlisted, were regarded as hard targets by the Confederates, who’d experienced the Irish reputation for tough fighting at key battles in the 1862 Peninsular Campaign, when the Union army came within a short distance of Richmond before retreating, unsettled by the Confederate’s remarkable new commander, Robert E Lee.

Emboldened by Lee’s audacity, the Rebel army invaded the North, losing narrowly at Antietam in Maryland, where Irish regiments refreshed their reputation by attacking the key strong point, a sunken road, pressurising the Confederate withdrawal south. Victory at Antietam prompted Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and discouraged both Britain and France from officially recognising the Confederacy.

But the Irish units would pay dearly for their reputation when on a wintry afternoon on December 13, 1862, much of their strength was lost in an assault over 800 yards of open ground to a low wall overlooking the Virginian town of Fredericksburg and defended by Confederate units commanded by Antrim native Robert Emmet McMillan, named after the Irish patriot. Regarded by historian Shelby Foot as the most courageous act of the conflict, it was also one of the costliest, resulting in over 80pc losses during six rushes on an impregnable position.

Confederate General George Pickett wrote to his fiancee: “Your soldier’s heart almost stood still as he watched those sons of Erin fearlessly rush to their death. The brilliant assault on Marye’s Heights of their Irish Brigade was beyond description. Why, my darling, we forgot they were fighting us, and cheer after cheer at their fearlessness went up along our lines.”

Seven months later, General Pickett’s own division, numbering 12,500, would itself be destroyed, suffering over 50pc losses, including 17-year-old Willie Mitchell, son of Fenian leader John Mitchell, trying to split the Union line by advancing over a mile of open ground on the final day of Gettysburg. It was the high water mark of the Confederacy, and the road to Washington was blocked at the centre for the Union by the Irish 69th Pennsylvania and the remainder of the Irish Brigade carrying the Harp and the Stars and Stripes side by side at the middle of the Union position.

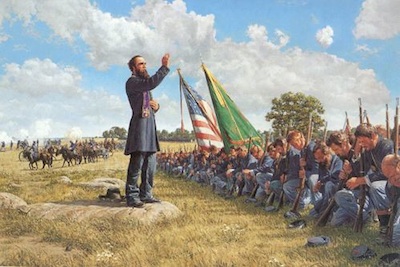

One of the most iconic images of the war is that of Fr Corby giving the sacrament of extreme unction to the Irish Brigade led by Galway-born Colonel Patrick Kelly, ordered forward to bolster a reckless salient in the Union position at Gettysburg. A Presbyterian in a nearby Scotch-Irish Pennsylvanian regiment, Robert Laird-Stewart, who would later become a Presbyterian minister, wrote: “The next command was delayed for a few moments and during that interval we were witnesses of an unusual scene which made a deep impression upon all who witnessed it. The Irish Brigade, whose green flag had been unfurled in almost every battlefield from Bull Run until this hour, stood in column of regiments in close order with bared heads while their chaplain priest, Fr Corby, stood upon a large boulder and seemed to be addressing the men.

“At a given signal every man of the command fell on his knees and with head bowed received from him the sacrament of extreme unction. Instinctively, every man of our Regiment took off his cap and no doubt many a prayer from men of Protestant faith, who could conscientiously not bow the knee in a service of that nature, went up to God in that impressive and awe-inspiring moment.”

Confederate morale, dampened by defeat at Gettysburg and followed in close order by the fall of its Mississippi fortress at Vicksburg, was lifted in September 1863 when Tuam-born Lieutenant Dick Dowling, together with 47 hand-picked Irish dockers, repulsed a 27-ship Union armada comprising 6,500 troops at Sabine Pass in Texas in a feat of gunnery described by Jefferson Davis as the Confederacy’s Thermopylae.

The USA emerged, not out of the penmanship of its founding fathers, who had determined all men were created equal, provided they were of the right colour, but from the outcome of an internal war during which 3pc of its population became casualties, and which tested the boundaries of a nascent democracy that would harvest the advantages of its geographic isolation and abundant natural resources to become the predominant global superpower.

In remembering the Irish dead in Flanders and Gallipoli let’s not forget those who fled the Famine and died reshaping the USA in the face of sectarianism and bigotry that characterised much popular feeling towards Irish Catholic immigrants before their conduct and the war redefined them.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)