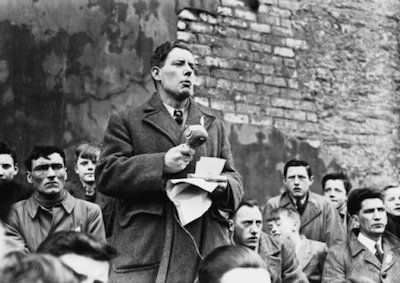

Seventy-one years ago Derry republican Hugh McAteer pulled off a series of daring feats and in the process made headlines around the world. Michael McMonagle looks at his extraordinary life.

Easter has always been an important time for Irish republicans as they commemorate the Easter Rising of 1916.

These days those commemorations usually take the form of marches or wreath laying ceremonies at republican monuments or in cemeteries but that was not always the case.

During the Second Word War, when the IRA was at a particularly low ebb as a result of internment on both sides of the border, a Derry IRA leader came up with a bold and imaginative way of commemorating the Easter Rising.

Hugh McAteer was born into a prominent nationalist family in the city and rose to become the first Derry-born IRA Chief of Staff and one of the most recognisable republican figures of his generation.

He grew up in a home rooted in nationalist politics which influenced him from a young age. One of his great-grandfathers was a ‘reader’ - someone who read newspapers to others at a time when many people were unable to read. During the 1840s he read ‘The Nation,’ Thomas Davis’ radical newspaper to his friends and neighbours.

Hugh McAteer followed his family tradition of radical politics and joined Na Fianna Eireann - the republican scouting movement - at an early age. He remembers one occasion in 1928, while drilling with the Fianna in a field, being surrounded by the RUC who fired over their heads.

Such experiences, together with his membership of the Gaelic League and reading republican newspapers, led him to join the IRA.

He moved from the Fianna to the IRA eighty years ago in 1933.

The young Derry man was also a member of the St Vincent de Paul Society and said that religious fervour and republicanism often went hand in hand. “Independence was nearly as strong in our minds as religion,” he said. “We would go out unthinkingly after Mass at 11.00am and we’d walk fourteen miles for our copy of An Phoblacht,” he added.

His initial IRA activities in Derry were limited and included crossing the border to Donegal to canvass for Fianna Fail in the 1933 elections.

He later recalled that he and his friends celebrated Fianna Fail’s victory by smashing windows.

Over the next decade however he rose through the ranks of the IRA to become a leading figure in the organisation in the North. By the early 1940s he was mainly based in Belfast and became involved in a power struggle as various factions vied for control of the IRA.

In 1941, alarmed at an excessively violent grouping within the Belfast IRA who regularly beat up other members, McAteer and another senior republican, Eoin MacNamee called a meeting of the Belfast IRA battalion in a house on the Falls Road to confront what they called ‘the belt and boot brigade.’ Anticipating a violent clash, McAteer summoned a company of Protestant IRA men, led by John Graham, as well as volunteers from rural areas, to wait close by and be prepared to storm the meeting with guns blazing if a fight broke out. Seeing McAteer and MacNamee armed the other faction backed down and a clash was avoided.

The IRA held provincial conventions throughout Ireland in a bid to reorganise and, owing to his seniority and his handling of the Belfast dispute, McAteer took charge of the Ulster convention.

The Derry man’s prominence in the IRA was highlighted in September of the following year when a young IRA man, Tom Williams, addressed his last letter to McAteer before his execution in Crumlin Road Jail.

In the letter, written just hours before he was hanged, the teenager paid tribute to McAteer’s leadership. “I am proud to know that you are our leader. My comrades and I are sure that you will use your utmost powers to free our dear, beloved country,” he wrote.

A week later, the publicity headquarters of the IRA’s Northern Command was raided and a number of senior republicans arrested. An entire copy of the IRA newspaper, ‘Republican News,’ ready for publication, was also seized. Following the raid, McAteer and a number of others sat up all night producing a further 6,000 copies of the paper for distribution.

A month later McAteer himself was arrested after being decoyed to the home of a boyhood friend who was by then a member of the RUC. McAteer, however, refused to have him executed for his actions.

The IRA leader was sentenced to 16 years in prison and was sent to Crumlin Road jail but did not remain there long.

On January 15, 1943 McAteer and three others used makeshift ropes and hooks to get onto the roof of the prison washroom and eventually over the wall to make their escape.

A reward of 3,000 pounds was offered for the recapture of any or all of the four.

The escape provided a propaganda boost to the IRA at the time and set in train a series of dramatic events, all involving McAteer.

In March a group of 21 prisoners escaped from Derry Jail through a tunnel which emerged in Harding Street. One of the prison’s inmates played the bagpipes to cover the sound of the tunnelling.

15 of the prisoners made it over the border in the back of a truck only to be apprehended by the Free State army in Donegal and were sent to the Curragh.

The escape however provided a morale boost for the organisation and gave McAteer the idea to stage another headline grabbing incident.

He decided, along with a group of other IRA men, to take over a cinema in Belfast and hold a public demonstration.

On Holy Thursday 1943 a group of sixteen volunteers, led by McAteer, entered the cinema two at a time and took over the exits and entrances.

The projection booth was also taken over and a slide was projected onto the screen which read; “This cinema has been commandeered by the Irish Republican Army for the purpose of holding the Easter Commemoration for the dead who died for Ireland.”

Jimmy Steele then read out 1916 Proclamation from the stage of the cinema and McAteer read out a statement outlining IRA policy for the coming year. They then held a minutes silence before making their escape.

The daring incident hit the headlines across Ireland and further afield and was even mentioned by Nazi propagandist Lord Haw Haw in his radio broadcast from Berlin that evening.

McAteer, then Chief of Staff, did not stay at large for long and was recaptured in November 1943. He remained in prison until 1954. Following his release he contested a number of elections in Derry as an independent republican candidate.

He drifted away from active republicanism in the 1960s but became reinvolved in the establishment of defence committees in Belfast in 1969 at the outbreak of the Troubles before his sudden death in 1970.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)