By Anne Cadwallader (for the Irish Independent)

One afternoon in 1999, four people sat around a table in the village of Camlough, south Armagh. One of them was me. Another was Ann Bracknell, whose husband, Trevor, an Englishman from Birmingham, had been shot dead in December 1975, two days after she had given birth to her only daughter, Roisin.

Ann’s oldest son, Alan, was also in the room. A quiet, dark-haired, besuited and serious young man, he said nothing throughout the meeting. The fourth and final person was Jimmy McCreesh, a veteran republican from south Armagh who had witnessed Trevor’s final moments.

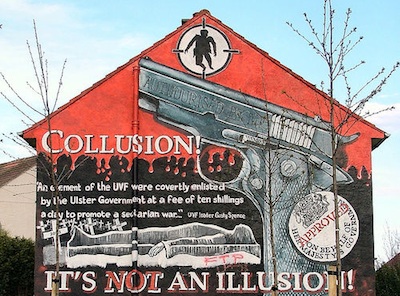

Jimmy was there to tell Ann, for the first time, exactly how Trevor had died. There were rumours in 1999 of possible collusion in the attack and I was there to record his words and ask Ann if she believed police officers or UDR soldiers had been involved.

The shooting had taken place in Donnelly’s Bar in Silverbridge where Trevor had gone to “wet the baby’s head”. Jimmy had been standing next to him when the muzzle of the sub-machine gun poked through the bar’s front door.

Outside, Patsy Donnelly had already been shot dead as he filled his car with petrol. Michael Donnelly, the bar owner’s son, had escaped the bullets and had run into the bar’s living quarters to escape the gang. Sadly he was killed when one of the gang tossed a bomb inside the pub.

At that meeting in Camlough in 1999, Jimmy began – in excruciating detail – to explain exactly how Trevor had died. I stopped him in mid-sentence, explaining this was too much for Ann to bear.

“No,” she said. “No one has ever explained to me how Trevor died. I want to hear it all.”

Mercifully, Jimmy’s account was that Trevor had not suffered. He had died the moment the bullets hit him. He was dead by the time the gang threw in the bomb that took his legs off at the knees.

We all left the meeting chastened. I wrote the story up as an incidence of possible collusion and didn’t see Alan or Ann Bracknell again for another 10 years.

What I didn’t know was that Alan subsequently decided, in his quiet but dogged way, to investigate the claims of collusion. He visited the Pat Finucane Centre in Derry and asked for help, eventually giving up his job as a quantity surveyor to become a full-time volunteer researcher with the centre.

His decision has led, nearly 15 years later, to the publication this week of my book ‘Lethal Allies: British Collusion in Ireland’.

Having discovered that, indeed, at least one RUC officer and one UDR soldier had been involved in murdering his father and the other two who died in the Donnelly’s Bar attack, Alan went on to investigate 120 other deaths.

I joined the centre nearly four years ago, met up with Alan again (to our joint surprise) and was asked to write up the results of that research. The outcome is in the book.

What turned those collusion “rumours” into fact? Well, first of all, the hours of hard work that Alan and other volunteer researchers put in at the British and Irish national archives. Hours more hard work in local newspaper libraries. Hours of gruelling conversations with bereaved relatives and eye-witnesses to the murders.

The Barron Reports into the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, with their appendices listing ballistic links between weapons, helped enormously – as did the sterling work of Justice for the Forgotten in Dublin when the Pat Finucane Centre realised its work dove-tailed across the border with the Northern research.

More and more families came on board. People who had never known of linked deaths began to realise they were all connected in one way or another (through perpetrators or forensic/ballistic evidence).

The final piece in the jigsaw came when the Historical Enquiries Team was set up. A flawed, imperfect, ad hoc and unpredictable truth-recovery mechanism, nevertheless it had access to the ‘Holy Grail’ – the RUC archives.

One team was set up to investigate collusion in counties Armagh and Tyrone. This team set about their work with dedication, honesty, diligence and integrity. Family after family received devastating reports citing collusion between UVF killers, police and soldiers.

The evidence mounted. One family was told their father’s killer, far from being a “cheese processor”, was a police reservist. Four orphaned children were told their parents’ killer was not a telecommunications engineer but a UDR soldier.

Why does this matter? Because the time lapse of over 35 years does not remove the imperative for justice. Because collusion fuelled the conflict. Because we must learn from the past. Who paid the price? The 120 dead and their families, who were lied to for over 35 years. But not for one instant do we say they were alone.

As Catholic confidence in law and order collapsed, and people looked to the IRA for their protection or became more tolerant of republican violence, then other soldiers and police officers also died unnecessarily.

Who is to blame? The loyalists? The corrupt police officers and UDR soldiers? Or the British and local Northern civil servants and politicians who knew it was going on and failed to halt collusion in its tracks?

Is the only lesson from history that we don’t learn from history? An agreed truth recovery process is needed, not only for all the North’s bereaved families but for our communities collectively to learn and move forward into a shared future.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)