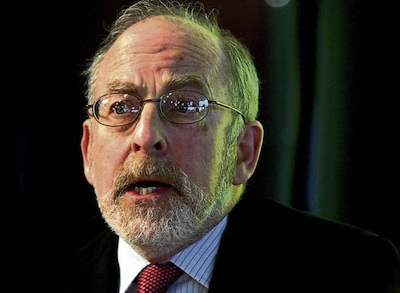

Statements by the governor of the 26-County Central Bank, Patrick Honohan, have placed him at the centre of a blame game over the banking crisis which collapsed the Irish economy.

Honohan’s comments that there were ‘no new issues’ arising from the release of the Anglo Irish Bank tapes have raised fears that the Central Bank may be attempting to conceal the truth in relation to the banking crisis which began in 2008.

Tapes of conversations between Anglo executives, whose deceptions saw the 26-County state required to take over losses of some 30 billion euro, were leaked earlier this year. The tapes are filled with ‘cowboy capitalist’ bravado and jibes at government officials and have infuriated the public who saw them as clear evidence of the Anglo board’s wrongdoing.

But despite the openly fraudulent activities of the banking chiefs, no-one has still been prosecuted for any crime. A public inquiry into the banking scandal has been repeatedly delayed, ostensibly due to police investigations.

Meanwhile, Irish politicians and government figures such as Honohan stand accused of protecting bank executives, presumably in the hope of limiting their own exposure to scandal and prosecution.

The Central Bank chief told a finance committee of the Dublin parliament this week that there was “no smoking gun” in relation to the content of the tapes.

“Because there is nothing more really than the telephone conversations, it’s not a sufficient evidential basis on which to ground a suspicion of a criminal offence,” he told the committee.

Sinn Fein deputy leader Mary Lou McDonald accused the governor of “sitting on his hands”, and she said the system, including the political system, chose to “look away” from the people who should be held to account.

Speaking directly to Mr Honohan, she said little had changed. “If that obnoxious, macho attitude was characteristic of the bankers and the system including the political system at the time, it would be fair to say it is characteristic of the system now,” she said.

Honohan, as the regulator of the Anglo-Irish Bank, should have made “bloody sure” that all of the tapes were listened to and scrutinised “to make absolutely sure that information and material is passed on to the relevant authorities,” she said.

She added: “I would have thought that that was the most basic requirement of somebody who would claim to be a regulator.”

Honohan made his comments in the same week he also embraced the forced eviction of homeowners facing mortgage arrears.

As left-wing organisations battled to prevent the eviction by bailiffs of a family from their home in Kanturk, County Kerry, homeless organisations such as the Simon Community have reported that homeless numbers are already up more than 80% this year.

Another report this week revealed that many young graduates are emigrating in increasing numbers.

Poor jobs, workfare and a blanket exclusion from the high salaries enjoyed by a previous generation have caused tens of thousands of Irish graduates to abandon the country, according to a report on austerity emigration by University College Cork.

More than 90% of those among aged 25 to 29 have lost a member of their circle of friends to emigration, while one in three have had an immediate family member emigrate since 2006.

But bankers such as Honohan are defiant, and that repossesions are part of the measures needed to restore international confidence in the Irish economy.

The Central Bank chief encouraged banks to prosecute such measures with greater determination.

“The indications are that the process is working, momentum is building, but there is some way to go,” he said.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)