Irish soldiers fighting for the British Army in India went on strike after hearing of British war crimes in Ireland on June 28 1920, 93 years ago this week.

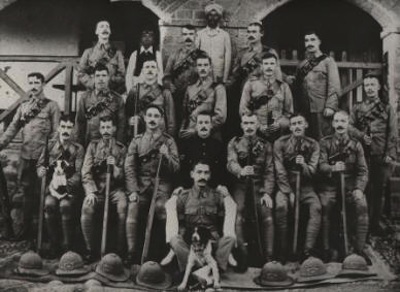

The Connaught Rangers were organised in 1881 as the county regiment of Galway, Leitrim, Mayo and Roscommon. Their two battalions were merged into one in 1914 following heavy losses at Mons and Marne. They also fought at Aisne, Messines, Armentienes and Ypres that year. They were moved to Mesopotamia in 1916 and Palestine in 1918 before being separated again into two battalions, the First being sent to India in October 1919. Nearly all the men who mutinied in 1920 were veterans of the Great War.

The Connaught Rangers were well known for their marching song, It’s a Long Way to Tipperary. The 2nd. Battalion sang this song on 13 August 1914 as they marched in parade order through the streets of the French port of Boulogne on their way to the front. War Correspondent George Curnock witnessed this incident and his report of it was printed in The Daily Mail on 18 August 1914. From that day, that music-hall song, written by Jack Judge in 1912, gained popularity amongst all the troops during the Great War.

On Sunday night, 27 June 1920, Joe Hawes, Paddy Sweeny, Patrick Gogarty, Stephen Lally and William Daly met in the canteen, Jullunder barracks, NE India, in the foothills of the Himalayas. They were veterans with twelve years service. Joe told the others of his experiences in Clare where he had been on holiday the year earlier and where the British authorities were stepping up repressive measures, theoretically against the republican movement, but where they proved elusive, beating and even killing likely looking young men. Newspapers and letters that had arrived the previous day told of the atrocities being committed by the ‘Black and Tans’.

The next morning, 8am 28 June 1920, William backed out, but the other four went to Lance Corporal John Flannery to give him the names of their families. They anticipated there was a high chance that they would be shot out of hand for what they were about to do and trusted him to get the true reasons for their execution to Ireland. They then reported to the guard room, asking to be arrested because they no longer wished to serve in the British Army. The news of their action spread fast, small groups of excited men could be seen standing in every direction, others were running here and there.

At 9am when the rest (46 men) of their ‘C’ company was parading, Jimmy Moran of Athlone stepped out of ranks and asked to be put in the guard room also. Twenty-nine other men also went with him, including the duty guard himself and his arms. The atmosphere in the guard room was giddy, with those in the crowded jail singing rebel songs and ‘Up the Republic!’ loud enough to be heard across the barracks.

Later that day ‘B’ Company (200 men) arrived at the barracks and hearing the singing halted at the guard room rather than march past. Their commanding officer, Col. Deacon arrived and told ‘B’ Company to wait while he addressed those inside. He was about to make a serious mistake, in his belief that regimental pride would solve the developing problem. He had those in the guard room come outside and form a line in front of him. He made an improvised, and to his own mind, very moving, speech in which he appealed to his own 33 years with the Rangers, their great history, the honours on the flag. Just at this point Joe Hawes stepped forward, interrupting him and said ‘all the honours on the Connaught Flag are for England. There are none for Ireland, but there will be one after today and it will be the greatest honour of them all.’ One of the mutineers, Pat Coleman, overheard the adjutant mutter to the Sergeant Major ‘when the men go, put Hawes back under arrest.’ Coleman shouted out ‘you won’t get the chance of Hawes, we are all going back. Left turn! Back to the guard room lads!’ Col. Deacon was in tears as over a hundred members of ‘B’ company ran over to the bars of the guardroom windows to talk excitedly with those inside. These soldiers were armed and they urged those inside to come out. This was a critical moment. A personal decision made by four soldiers to leave the army became a fully blown mutiny of some 150 soldiers. Those inside poured back out to cheers.

The officers ran. They went first to ‘D’ Company and cancelled its parade in the hope of keeping them out of the mutiny. The rebels on the other hand, went to the regimental theatre where the bugler sounded assembly thus circumventing the officers as almost the entire 500 members of rank and file of the Connaught Rangers present at the barracks fell in. For the first fifteen minutes the meeting was completely chaotic with men chiming in as they felt like. Then a committee was elected, with a proposer, seconder and show of hands. All the votes were unanimous: Paddy Sweeny, Corporal James Davies, Patrick Gogarty, Lance-Corporal John Flannery, Jimmy Moran, Lance-Corporal McGowan and Joe Hawes. John Flannery was elected spokesperson.

The meeting was then dismissed with the decision made to obey only the committee and not any officer. The seven leaders then quickly came to agreement as to their aims and methods. Their priority was to make the protest known to the world. In the meantime they resolved to retain their arms, double the guard of the barracks, guard the alcohol, change the union flag to the tricolour, form special flying sentries to patrol the grounds at night, appoint a guard over those men who did not wish to join the mutiny – for their own safety. A reassembled meeting after dinner voted on each of these decisions, which were then taken to Col. Deacon. Meanwhile green, white and orange rosettes appeared on the mutineers’ breasts.

The commanding officer of the Jullunder barracks was Lt. Col. Leeds. He arrived and on hearing of the mutiny sought a meeting with the two main leaders: Flannery and Hawes. ‘Do you realise how serious this is?’ He pointed out the consequences of mutiny for those involved and added that in the current climate it could act as a signal for a rising by the native population. To this Hawes responded ‘if I am to be shot, I would rather be shot by an Indian than an Englishman.’ This statement was noted by the adjutant, along with the disrespectful attitude shown by Hawes’ smoking a cigarette throughout the interview.

Flannery’s response to this argument was later to go to the bazaar and explain the mutiny to the local traders, who expressed great sympathy and made green white and orange cloth available. Flannery reminded the Indian merchants of the Amritsar massacre the previous year (13 April 1919, the British Army opened fire on 10,000 unarmed demonstrators and festival goers, killing 400 and wounding 1200) and said that ‘the same forces were shooting down our fellow countrymen and women in Ireland.’ One of the merchants replied ‘had I a few divisions of men like the Connaught Rangers I would free my country in a very short time.’

Major N. Farrell of ‘B’ Company next attempted to form up his men. Joe Hawes ordered them back to their bungalow. The men obeyed Hawes.

On the morning of the 29 June Col. Jackson arrived at the barracks, as the representative of Sir General Munroe, C. I. C. all of India. A white flag flew from his car. Jackson was surprised when he found a disciplined parade lined up. He met with the leaders and told them that the barracks would be retaken ‘even if it requires every soldier in India.’ He pointed out that they were encircled and had nowhere to go. He also urged them to consider the danger from the native population.

The British army had indeed moved fast on news of the mutiny. On 1 July two battalions of the Seaforth Highlanders and South Wales Borders along with a company of machine gunners and a battery of artillery arrived at the camp in full battle order. Jullunder was not a walled-in barracks. The rebels had no chance of further resistance.

Having called the men together, they advocated passive resistance by all, with the aim of preventing the execution of the leaders by sticking together until all were dismissed from the army. Everyone had to right to leave at this point and some eighty men did so, but the other 420 cheered the Irish Republic, including the English soldiers, and surrendering their weapons, marched out to a prison camp, lead by John Flannery. Along their route the newly arrived soldiers marched beside them, arms ready. The internment camp was guarded with barbed wire and a machine gun post. The camp was deliberately set up in a foul area near a cess pit. It had inadequate shade and water. The prospect of disease breaking out was a very real one and the mutineers were all suffering various degrees of sun stroke, 30 – 40 men were seriously ill after two days. They were saved from any deaths by the intervention of the medical officer of the station, Dr. Carney, who threatened to resign unless they were moved to another site.

On 2 July they were marched to another, walled, compound. Major Johnny Payne was the officer in charge of the move, he was drunk and angry. Half way there he called a halt and said ‘I am going to call out twenty names, and those men are to fall in at this spot.’ The names he then shouted were the seven committee members and thirteen others. No one moved. So Payne pointed to Tommy Moran and ordered his troops, 30 South Wales Borders, to pull him out. The mutineers closed around Moran and protected him. The soldiers who tried to push into the crowd were knocked over and disarmed. Payne ordered the rest to fix bayonets. He called out the 20 names again. Still no response. Then he gave the order ‘five rounds, stand and load.’ He pulled a handkerchief out of his pocket and said ‘I am going to shoot ye fuckers.’ In a violent rage he turned to his men. ‘When I drop this handkerchief fire and spare no man. Shoot them down like dogs.’ Someone shouted out to him ‘you can do your bloody best.’ At this moment the seventy year old army chaplain, Fr. Livens, a Belgian priest came running over. ‘Major Payne, in the name of God what is this all for.’ Payne replied ‘I am going to shoot these men.’ The priest turned to them. ‘Are you ready to die?’ All answered ‘yes.’ The priest then stepped back with us. ‘Fire away Major Payne, I’ll die with them.’ A horseman was coming fast from the barracks blowing a whistle. The major waited for him. It was Col. Jackson. In front of all the mutineers he shouted at Payne. ‘Who gave you the orders to do this major?’ Without giving him a chance to reply he continued ‘get away out of this and take those men with you.’ The massacre had been averted.

Due to the harsh conditions and heat sickness a number of mutineers gave up. Then a group of English soldiers came to the committee saying that seeing as some Irishmen were back in the service, they wished to withdraw. Some English soldiers, however, stayed with their comrades until the very end.

By 7 July the authorities were able to separate 47 mutineers from the rest. These were driven to a compound with a machine gun on the wall and no tents inside. For two days they had no food or water until Dr. Carney came. ‘Stick it out Hawes, I’ll get you out of here soon.’ He whispered. The next day they were brought back to the barracks by lorry and placed 5 to a cell. The rest of the mutineers were then paraded and addressed by Col. Jackson. He offered them the chance to return to their ranks without any reprisal or mark on their record. From the cells the leaders shouted at the men not to obey, but their spirit was broken. They fell in to their respective companies like a flock of sheep. One man was left alone on the parade square, Lance Corporal Willis. Major Payne left his position. ‘Willis, you and I fought together in the trenches. Why are you so foolish. Those men over in the cells are going to their deaths. I will give you five minutes to consider and if you fall in with the loyal men I will do everything I can for you.’ There was a short interval, before Willis replied. ‘I would rather die with the men over in the cells no matter what kind of death it is than fall in under you, with this shower of bastards here.’ Willis was then marched over to the cells under escort, accompanied by the wild cheers of those inside.

The 48 were sent to prison in Dagshai for months, awaiting court martial, where they were joined by Jim Joseph ‘J. J.’ Daly (from Mullingar, Co. Westmeath) and 40 men from Solon. These men were also Connaught Rangers, 300 men from ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies had been based some ten miles from Jullunder and when they heard of their comrades’ action they decided to join the mutiny. The 40 had taken over a bungalow and hoisted the tricolour. They had been persuaded by the camp priest, Fr. Baker (who also wrote a short memoir), to leave their arms in the armoury, but the officers had placed two of their own, Lt. Walsh and McSweeny as guards. When rumours came that troops were approaching the mutineers decided to try and take the armoury. Daly led a rush, hoping their numbers would dismay the officers, but both opened fire. Pat Egan, a mutineer was shot through the chest but lived, another mutineer, Sears, was less fortunate, dying in front of the officers. So too was a private Smith, not a participant and some distance away, but a bullet hit him in the head and he died on the spot. Fr. Baker intervened to stop the shooting, with the armoury still in the hands of the officers. Then Fr. Baker and Daly went to the hospital with the wounded Egan. Daly asked the doctor for a drink but Fr. Baker noticed something and said ‘I’ll drink a little of it first.’ At which point the doctor spilled it all. With the arrival of loyalist troops the mutineers were arrested.

Due to the sympathy of the Indian lavatory cleaner and the barber of Dagshai jail, followers of Ghandi, six men made a break out while Paddy Sweeny kept the attention of the guards on the sky with a discussion of astronomy. They walked the six miles to Solon and made off with canteen supplies, especially cigarettes. ‘J. J.’ wanted to burn down the whole of the stores but Hawes pointed out that the men in jail would then miss out of their share of the haul. Hawes also commented in his testimony ‘it might be wondered why we did not make a break for freedom that night or any other night, but you must remember that we were in an alien country, thousands of miles from home, even unable to speak the language. Everyone would be our enemy both the king’s men and the native Indians to whom none of us could explain our position over the language barrier. Soldiers were not popular in India at that time.’ They crept back in with their loot which was distributed to all.

A core group of 16 men were brought to trial 30 August 1920. Sadly many Irish soldiers bore witness against them. One English sergeant spoke for them and when asked by the court why he joined the mutiny when he was not Irish, he replied that ‘these men had stood beside me in the trenches and were my comrades.’ At the end of the trial Flannery cracked and handed up a statement written in pencil on poor quality paper. When it was read out his comrades rushed at him and had to be driven back at bayonet point. Flannery claimed that he only acted as spokesman for the mutiny in order to moderate it and prevent any deaths. It also meant that he could keep officers fully aware of developments and the thinking of the men. The prosecutor immediately declared that ‘I hope the Court will not accept the statement of Lance Corporal John Flannery because it is obvious that he is only trying to lighten his own sentence at the expense of his comrades.’ From this incident onwards Flannery was kept in a guard room outside the main gate of the prison. He and Hawes never spoke to each other again and even when, much later, in the 1970’s the Irish State wished to commemorate the mutiny, Hawes refused to attend if Flannery would be present.

61 men were sentenced, with 14 (including Flannery) getting the death sentence, the rest terms of imprisonment from 1 to 21 years. Helped by the situation in Ireland, where British policy was changing from repression to negotiation, the C. I. C. of India commuted all the life sentences except for that over ‘J. J.’ Daly. He was shot on 2 November 1920 by a firing party of London Fusiliers. There was a rumour that the local Indian population would attempt to storm the jail so several miles around the jail was put under curfew. Daly gave his few belongings and a last postcard to Hawes. It is available in the Military Bureau and is nearly indecipherable with very many crowded scrawlings that seem to oscillate between real dread and comforting thoughts about the cause of Ireland. Daly was the last British soldier shot for mutiny, but his was not quite the last execution. August 1943 witnessed the hanging of three Indian mutineers and in January 1946 a British soldier was executed after being convicted of war treason.

After negotiations between the Provisional Government of the Free State and the British Government, all prisoners were released 9 January 1923. The mutineers were later honoured and given pensions by the Irish state.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)