By Fintan O'Toole (for the Irish Times)

A temptation newspaper columnists should avoid is the urge to make links between different stories simply because they happen to be in the air at the same time. But here goes anyway.

Is there not some kind of connection between two big aspects of contemporary Ireland: the extraordinary apparatus of repression whose existence we are finally acknowledging; and the sense of powerlessness with which most Irish people have faced the current crisis?

Listening last week to Enda Kenny’s courageous and superbly crafted speech of apology to the Magdalene women, one phrase struck me especially hard. The Taoiseach spoke of the “‘values’ of the time that welcomed the compliant, obedient and lucky ‘us’ and banished the more problematic, spirited or unlucky ‘them’.” It raised an obvious question: when, if ever, did those values change?

HABIT OF MIND

Are these just values “of the time” or do they form a habit of mind that is still hard to shake off? At what point did Irish society lose its tendency to value compliance and obedience over awkwardness and difference? The obvious answer is surely “never”.

If there is more continuity than we like to admit between the culture of compliance in a “cruel, pitiless” Ireland of the past and the strange passivity of the present day, this would not be all that surprising.

The sheer scale of the Irish system of institutional incarceration is breathtaking. Eoin O’Sullivan and Ian O’Donnell, in their recent book, Coercive Confinement in Ireland, show that the State locked up one in every 100 of its citizens in Magdalene laundries, industrial schools, mental hospitals or “mother and baby” homes.

At any given time between 1926 and 1951, there were about 31,000 people in these institutions - only a small fraction of whom had committed any crime. The 1 per cent figure also applied to children - one child in every hundred was enslaved in an industrial school.

This was our Great Purge, our way of establishing religious, social and moral “purity” by locking up and “correcting” potential deviants. This level of “coercive confinement” is extreme for any democratic society. In 1931, the Soviet gulag held about 200,000 prisoners - from a population of 165 million.

The Irish system held 31,000 people - from a population of three million.

I am not, I should stress, comparing the two systems directly or suggesting that Ireland was a totalitarian dictatorship - merely trying to give some sense of the relative scale of the operation.

MASS EMIGRATION

Mass emigration “banished” most of the “misfits” who would otherwise have been locked up. And many priests, nuns and brothers were themselves institutionalised in a way that was at best semi-voluntary. (Teaching orders, for example, used their own schools to recruit impressionable children.)

The effects of something as large as this don’t just disappear in a generation or two.

This is especially so because the reach of the system went far beyond those who were actually locked up.

It was less violent than its equivalents in totalitarian states, but it had two exquisitely insidious refinements. One is that it was entirely obvious - there was no distant Siberia.

The institutions of confinement were not only not hidden, they were the most prominent buildings in many Irish towns.

This meant both that they served as a general warning to the entire population but also that they invited collusion - Irish people came to accept this brutal system, not as the hated imposition of a tyrant or invader, but as our Irish “normality”.

The other refinement was even more psychically destructive. The system managed to make families in many cases the agents of harm to their own members. It is truly terrible when the secret police come and take you away to lock you up for some unknown crime. It is far, far worse, when your own mother and father play the role of the secret police.

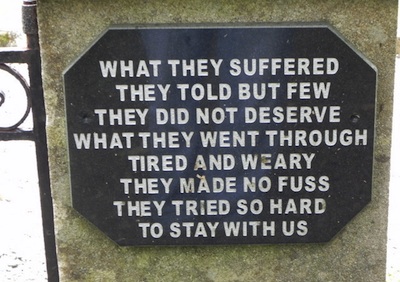

Many parents and siblings struggled heroically to protect their loved ones. But too many fathers left daughters at the doors of institutions and told them never again to darken the doors of home; too many mothers got rid of their “flighty” daughters for fear they might bring shame on the family; too many siblings were happy to see an awkward brother or sister locked away in a mental hospital.

This surely is where the worst damage was done to the culture as a whole.

The system taught a whole society very deep habits of collusion, of evasion and, perhaps most insidiously of all, of adaptation.

Have we really unlearned those terrible lessons so thoroughly that we can say with confidence that we no longer adapt ourselves to grotesque realities?

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)