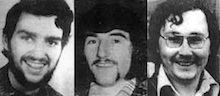

A profile of the three members of the Irish National Liberation Army who died alongside seven IRA Volunteers, on hunger strike for political status, thirty years ago this year.

Patsy O’Hara - A determined and courageous Derryman

Twenty-three-year-old Patsy O’Hara from Derry city, was the former leader of the Irish National Liberation Army prisoners in the H-Blocks, and joined IRA Volunteer Raymond McCreesh on hunger strike on March 22nd, three weeks after Bobby Sands and one week after Francis Hughes.

Patsy O’Hara was born on July 11th, 1957 at Bishop Street in Derry city.

His parents owned a small public house and grocery shop above which the family lived. His eldest brother, Sean Seamus, was interned in Long Kesh for almost four years. The second eldest in the family, Tony, was imprisoned in the H-Blocks - throughout Patsy’s hunger strike - for five years before being released in August of this year, having served his full five-year sentence with no remission.

The youngest in the O’Hara family is twenty-one-year-old Elizabeth.

Before ‘the troubles’ destroyed the family life of the O’Haras, and the overwhelming influence of being an oppressed youth concerned about his country drove Patsy to militant republicanism, there is the interesting history of his near antecedents which must have produced delight in Patsy’s young heart.

GRANDFATHER

Patsy’s maternal grandfather, James McCluskey, joined the British army as a young man and went off to fight in the First World War. He received nine shrapnel wounds at Ypres and was retired on a full pension.

However, on returning to Ireland his patriotism was set alight by Irish resistance and the terror of British rule. He duly threw out his pension book, did not draw any more money and joined the Republican Movement. He transported men and weapons along the Foyle into Derry in the ‘twenties.

He inherited a public house and bookmakers, in Foyle Street, and was a great friend of Derry republican Sean Keenan’s father, also named Sean.

Mrs. Peggy O’Hara can recall ‘old’ Sean Keenan being arrested just before the out break of the Second World War. Her father’s serious illness resulted in him escaping internment and he died shortly afterwards in 1939.

Mrs. O’Hara’s aunt was married to John Mulhern, a Roscommon man, who was in the RIC up until its disbandment in 1921.

“When my father died in 1939 - says Mrs O’Hara, - “John Mulhern, who was living in Bishop Street, and owned a bar and a grocery shop, took us in to look after us. I remember him telling us that he didn’t just go and join the RIC, but it was because there were so many in the family and times were hard.

“My father was a known IRA man and my uncle reared me, and I was often slagged about this. Patsy used to hear this as a child, but Patsy was a very, very straight young fellow and he was a wee bit bigoted about my uncle being a policeman.

“But a number of years ago Patsy came in to me after speaking to an old republican from Corrigans in Donegal, and Patsy says to me, ‘You’ve nothing to be ashamed of, your uncle being a policeman, because that man was telling me that even though he was an RIC man, he was very, very helpful to the IRA!”

FAMILY

The trait of courage which Patsy was to show in later years was in him from the start, says Mr. O’Hara. “No matter who got into trouble in the street outside, Patsy was the boy to go out and do all the fighting for him. He was the fighting man about the area and didn’t care how big they were. He would tackle them. I even saw him fighting men, and in no way could they stop him. He would keep at them. He was like a wee bull terrier!”

Apparently, up until he was about twelve years of age, Patsy was fat and small, “a wee barrel” says his mother. Then suddenly he shot up to grow to over six foot two inches.

Elizabeth, his sister, recalls Patsy: “He was a mad hatter. When we were young he used to always play tricks on me, mother and father. We used to play a game of cards and whoever lost had to do all the things that everybody told them.

“We all won a card game once and made Patsy crawl up the stairs and ‘miaow’ like a cat at my mother’s bedroom door. She woke up the next day and said, ‘am I going mad? I think I heard a cat last night’ and we all started to laugh.”

The O’Haras’ house was open to all their children’s friends, and again to scores of the volunteers who descended on Derry from all corners of Ireland when the RUC invaded in 1969. But before that transformation in people’s politics came, Mrs. O’Hara still lived for her family alone.

She was especially proud of her eldest son, Sean Seamus who had passed his eleven plus and went to college.

PROTESTS

When Sean was in his early teens he joined the housing action group, around 1967, Mrs. O’Hara’s conception of which was Sean helping to get people homes.

“But one day, someone came into me when I was working in the bar, and said, ‘Your son is down in the Guildhall marching up and down with a placard!

“I went down and stood and looked and Finbarr O’Doherty was standing at the side and wee fellows were going up and down. I went over to Sean and said, ‘Who gave you that? He said, Finbarr!’ I took the placard off Sean and went over to Finbarr, put it in his hand, and hit him with my umbrella.’

Mrs. O’Hara laughs when she recalls this incident, as shortly afterwards she was to have her eyes opened.

“After that, I went to protests wherever Sean was, thinking that I could protect him! I remember the October 1968 march because my husband’s brother, Sean, had just been buried.

“We went to the peaceful march over at the Waterside station and saw the people being beaten into the ground. That was the first time that I ever saw water cannons, they were like something from outer space.

“We thought we had to watch Sean, but to my astonishment Patsy and Tony had slipped away, and Patsy was astonished and startled by what he saw.”

INCIDENT

Later, Patsy was to write about this incident: “The mood of the crowd was one of solidarity. People believed they were right and that a great injustice had been done to them. The crowds came in their thousands from every part of the city and as they moved down Duke Street chanting slogans, ‘One man, one vote’ and singing ‘We shall overcome’ I had the feeling that a people united and on the move, were unstoppable.”

IRSP

Shortly after his release in April 1975, Patsy joined the ranks of the fledgling Irish Republican Socialist Party, which the ‘Sticks’, using murder, had attempted to strangle at birth. He was free only about two months when he was stopped at the permanent check-point on the Letterkenny Road whilst driving his father’s car from Buncrana in County Donegal.

The Brits planted a stick of gelignite in the car (such practice was commonplace) and he was charged with possession of explosives. He was remanded in custody for six months, the first trial being stopped due to unusual RUC ineptitude at framing him. At the end of the second trial he was acquitted and released after spending six months in jail.

In 1976, Patsy had to stay out of the house for fear of constant arrest. That year, also, his brother, Tony, was charged with an armed raid, and on the sole evidence of an alleged verbal statement was sentenced to five years in the H-Blocks.

Despite being ‘on the run’ Patsy was still fond of his creature comforts!

His father recalls: “Sean Seamus came in late one night and though the whole place was in darkness he didn’t put the lights on. He went to sit down and fell on the floor. He ran up the stairs and said: ‘I went to sit down and there was nothing there’

“Patsy had taken the sofa on top of a red Rover down to his billet in the Brandywell. Then before we would get up in the morning he would have it back up again. When we saw it sitting there in the morning we said to Sean: ‘Are you going off your head or what? and he was really puzzled.”

IMPRISONED

In September 1976, he was again arrested in the North and along with four others charged with possession of a weapon. During the remand hearings he protested against the withdrawal of political status.

The charge was withdrawn after four months, indicating how the law is twisted to intern people by remanding them in custody and dropping the charges before the case comes to trial.

In June 1977, he was imprisoned for the fourth time. On this occasion, after a seven-day detention in Dublin’s Bridewell, he was charged with holding a garda at gunpoint. He was released on bail six weeks later and was eventually acquitted In January 1978.

Whilst living in the Free State, Patsy was elected to the ard chomhairle of the IRSP, was active in the Bray area, and campaigned against the special courts.

In January 1979, he moved back to Derry but was arrested on May 14th, 1979 and was charged with possessing a hand-grenade.

In January 1980, he was sentenced to eight years in jail and went on the blanket.

HUNGER STRIKE

What were Mrs. O’Hara’s feelings when Patsy told her he was going on hunger strike?

“My feelings at the start, when he went on hunger strike, were that I thought that they would get their just demands, because it is not very much that they are asking for. There is no use in saying that I was very vexed and all the rest of it. There is no use me sitting back in the wings and letting someone else’s son go. Someone’s sons have to go on it and I just happen to be the mother of that son.”

PRINCIPLES

Writing shortly before the hunger strike began, Patsy O’Hara grimly declared: “We stand for the freedom of the Irish nation so that future generations will enjoy the prosperity they rightly deserve, free from foreign interference, oppression and exploitation. The real criminals are the British imperialists who have thrived on the blood and sweat of generations of Irish men.

“They have maintained control of Ireland through force of arms and there is only one way to end it. I would rather die than rot in this concrete tomb for years to come.

Patsy witnessed the baton charges and said: “The people were sandwiched in another street and with the Specials coming from both sides, swinging their truncheons at anything that moved. It was a terrifying experience and one which I shall always remember.”

Mr. and Mrs. O’Hara believe that it was this incident when Patsy was aged eleven, followed by the riots in January 1969 and the ‘Battle of the Bogside’ in August 1969 that aroused passionate feelings of nationalism, and then republicanism, in their son. “Every day he saw something different happening,” says his father. “People getting beaten up, raids and coffins coming out. This was his environment.”

JOINED

In 1970, Patsy joined na Fianna Eireann, drilled and trained in Celtic Park.

Early in 1971, and though he was very young, he joined the Patrick Pearse Sinn Fein cumann in the Bogside, selling Easter lilies and newspapers. Internment, introduced in August 1971, hit the O’Hara family particularly severely with the arrest of Sean Seamus in October. “We never had a proper Christmas since then” says Elizabeth. “When Sean Seamus was interned we never put up decorations and our family has been split-up ever since then.”

Shortly after Sean’s arrest Patsy, one night, went over to a friend’s house in Southway where there were barricades. But coming out of the house, British soldiers opened fire, for no apparent reason, and shot Patsy in the leg. He was only fourteen years of age and spent several weeks in hospital and then several more weeks on crutches.

BLOODY SUNDAY

On January 30th, 1972, his father took him to watch the big anti-internment march as it wound its way down from the Creggan. “I struggled across a banking but was unable to go any further. I watched the march go up into the Brandywell. I could see that it was massive. The rest of my friends went to meet it but I could only go back to my mother’s house and listen to it on the radio,” said Patsy.

Asked about her feelings over Patsy be coming involved in the struggle, Mrs. O’Hara said: “After October 1968, I thought that that was the right thing to do. I am proud of him, proud of them all”.

Mr O’Hara said: “Personally speaking, I knew he would get involved. It was in his nature. He hated bullies al his life, and he saw big bullies in uniform and he would tackle them as well.

Shortly after Bloody Sunday, Patsy joined the ‘Republican Clubs’ and was active until 1973, “when it became apparent that they were firmly on the path to reformism and had abandoned the national question”.

INTERNED

From this time onwards he was continually harassed, taken in for interrogation and assaulted.

One day, he and a friend were arrested on the Briemoor Road. Two saracens screeched to a halt beside them. Patsy later described this arrest: “We were thrown onto the floor and as they were bringing us to the arrest centre, we were given a beating with their batons and rifles. When we arrived and were getting out of the vehicles we were tripped and fell on our faces”.

Three months later, after his seventeenth birthday, he was taken to the notorious interrogation centre at Ballykelly. He was interrogated for three days and then interned with three others who had been held for nine days.

“Long Kesh had been burned the week previously” said Patsy, “and as we flew above the camp in a British army helicopter we could see the complete devastation. When we arrived, we were given two blankets and mattresses and put into one of the cages.

“For the next two months we were on a starvation diet, no facilities of any” kind, and most men lying out open to the elements...

“That December a ceasefire was announced, then internment was phased out.” Merlyn Rees also announced at the same time that special category status would be withdrawn on March 1st, 1976. I did not know then how much that change of policy would effect me in less than three years”.

Patsy O’Hara died at 11.29 p.m. on Thursday, May 21st - on the same day as Raymond McCreesh with whom he had embarked on the hunger-strike sixty-one days earlier.

Even in death his torturers would not let him rest. When the O’Hara family been broken and his corpse bore several burn marks inflicted after his death.

Kevin Lynch - A loyal, determined republican with a great love of life

The eighth republican to join the hunger-strike for political status, on May 23rd, following the death of Patsy O’Hara, was twenty-five-year-old fellow INLA Volunteer Kevin Lynch from the small, North Derry town of Dungiven who had been imprisoned since his arrest in 1976.

A well-known and well liked young man in the closely-knit community of his home town, Kevin was remembered chiefly for his outstanding ability as a sportsman, and for qualities of loyalty, determination and a will to win which distinguished him on the sports field and which, in heavier times and circumstances, were his hallmarks as an H-Block blanket man on hunger strike to the death.

Kevin Lynch was a happy-go-lucky, principled young Derry man with an enthusiastic love of life, who was, as one friend of his remarked - a former schoolteacher of Kevin’s and an active H-Block campaigner: “the last person, back in 1969, you would have dreamed would be spending a length of time in prison.”

The story of Kevin Lynch is of a light-hearted, hard-working and lively young man, barely out of his teens when the hard knock came early one December morning nearly five years ago, who had been forced by the British occupation of his country to spend those intervening years in heroic refusal to accept the British brand of ‘criminal’ and in the tortured assertion of what he really was - a political prisoner.

PARK

Kevin Lynch was born on May 25th, 1956, the youngest of a family of eight, in the tiny village of Park, eight miles outside Dungiven. His father, Paddy, (aged 66), and his mother, Bridie, (aged 65), whose maiden name is Cassidy, were both born in Park too, Paddy Lynch’s family being established there for at least three generations, but they moved to Dungiven twenty years ago, after the births of their children.

Paddy Lynch is a builder by trade, like his father and grandfather before him - a trade which he handed down to his five sons: Michael (aged 39), Patsy (aged 37), Francis (aged 33), Gerard (aged 27), and Kevin himself, who was an apprenticed bricklayer. There are also three daughters in the family: Jean (aged 35), Mary (aged 30), and Bridie (aged 29).

Though still only a small town of a few thousand, Dungiven has been growing over the past twenty years due to the influx of families like the Lynches from the outlying rural areas. It is an almost exclusively nationalist town, garrisoned by a large and belligerent force of RUC and Brits. In civil rights days, however, nationalists were barred from marching in the town centre.

Nowadays, militant nationalists have enforced their right to march, but the RUC still attempt to break up protests and the flying of the tricolour (not in itself ‘illegal’ in the six counties) is considered taboo by the loyalist bigots of the RUC.

Support in the town is relatively strong, Dungiven having first-hand experience of a hunger strike last year when local man Tom McFeeley went fifty-three days without food before the fast ended on December 18th. Apart from Tom McFeeley and Kevin Lynch other blanket men from the town are Kevin’s boyhood friend and later comrade Liam McCloskey - himself later to embark on hunger strike - and former blanket man Eunan Brolly, who was released from the H-Blocks last December.

SCHOOL

Kevin went to St. Canice’s primary school and then on to St. Patrick’s intermediate, both in Dungiven. Although not academically minded - always looking forward to taking his place in the family building business - he was well-liked by his teachers, respected for his sporting prowess and for his well-meant sense of humour. “Whatever devilment was going on in the school, you could lay your bottom dollar Kevin was behind it,” remembers his former schoolteacher, recalling that he took great delight in getting one of his classmates, his cousin Hugh (‘the biggest boy in the class - six foot one’) “into trouble”. But it was all in fun - Kevin was no troublemaker, and whenever reprimanded at school, like any other lively lad, would never bear a grudge.

Above all, Kevin was an outdoor person who loved to go fishing for sticklebacks in the river near his home, or off with a bunch of friends playing Gaelic (an outdoor disposition which must have made his H-Block confinement even harder to bear).

GAMES

His great passion was Gaelic games playing Gaelic football from very early on, and then taking up hurling when he was at St. Patrick’s.

He excelled at both.

Playing right half-back for St. Patrick’s hurling club, which was representing County Derry, at the inaugural Feile na nGael held in Thurles, County Tipperary, in 1971, Kevin’s performance - coming only ten days after an appendix operation - was considered a key factor in the team’s victory in the four-match competition played over two days.

The following season Kevin was appointed captain of both St. Patrick’s hurling team and the County Derry under-16 team which went on in that season to beat Armagh in the All Ireland under-16 final at Croke Park in Dublin.

Later on, while working in England, he was a reserve for the Dungiven senior football team in the 1976 County Derry final.

Kevin’s team, St. Canice’s, was beaten 0-9 to 0-3 by Sarsfields of Ballerin, and he is described in the match programme as “a strong player and a useful hurler”. Within a short space of time after this final, Kevin would be in jail, as would two of his team mates on that day, Eunan Brolly and Sean Coyle.

QUALITIES

The qualities Kevin is remembered for as a sportsman were his courage and determination, his will to win, and his loyalty to his team mates. Not surprisingly the local hurling and football clubs were fully behind Kevin and his comrades in their struggle for the five demands, pointing out that Kevin had displayed those same qualities in the H-Blocks and on hunger strike.

He was also a boxer with the St. Canice’s club, once reaching the County Derry final as a schoolboy, but not always managing as easily as he achieved victory in his first fight!

Just before the match was due to start his opponent asked him how many previous fights he’d had. With suppressed humour, Kevin answered “thirty-three” so convincingly that his opponent, overcome with nervous horror, couldn’t be persuaded into the ring.

At the age of fifteen, Kevin left school and began to work alongside his father. Although lively, going to dances, and enjoying good crack, he was basically a quiet, determined young fellow, who stuck to his principles and couldn’t easily be swayed.

Like any other family in Dungiven, the Lynches are nationally minded, and young Kevin would have been just as aware as any other lad of his age of the basic injustices in his country, and would have equally resented the petty stop-and-search harassment which people of his age continually suffered at the hands of Brits and RUC.

The Lynches were also, typically, a close family and in 1973, at the age of sixteen, Kevin went to England to join his three brothers, Michael, Patsy and Gerard, who were already working in Bedford.

Both Bedford and its surrounding towns, stretching from Hertfordshire to Buckinghamshire and down to the north London suburbs, contain large Irish populations, and the Lynches mixed socially within that, Kevin going a couple of times a week to train with St. Dympna’s in Luton or to Catholic clubs in Bedford or Luton for a quiet drink and a game of snooker. He even played an odd game of rugby while over there.

But Kevin never intended settling in England and on one of his occasional visits home (“he just used to turn up”), in August 1976, he decided to stay in Dungiven.

INLA

Shortly after his return home, coming away from a local dance, he and nine other young lads were put up against a wall by British soldiers and given a bad kicking, two of the lads being brought to the barracks.

Kevin joined the INLA around this time, maybe because of this incident in part, but almost certainly because of his national awareness coming from his cultural love of Irish sport, as well as his courage and integrity, made him determined to stand up both for himself and his friends.

“He wouldn’t ever allow himself to be walked on”, recalls his brother, Michael. And he had always been known for his loyalty by his family, his friends, his teammates, and eventually by his H-Block comrades.

However, within the short space of little more than three months, Kevin’s active republican involvement came to an end almost before it had begun. Following an ambush outside Dungiven, in November ‘76, in which an RUC man was slightly injured, the RUC moved against those it suspected to be INLA activists in the town.

On December 2nd, 1976, at 5.40 a.m. Brits and RUC came to the Lynch’s home for Kevin. “We said he wasn’t going anywhere before he’d had a cup of tea”, remembers Mr. Lynch, “but they refused to let him have even a glass of water. The RUC said he’d be well looked after by then.”

Also arrested that day in Dungiven were Sean Coyle, Seamus McGrandles, and Kevin’s schoolboy friend Liam McCloskey, with whom he was later to share an H-Block cell.

Kevin was taken straight to Castlereagh, and, after three days’ questioning, on Saturday, December 4th, he was charged and taken to Limavady to be remanded in custody by a special court. The string of charges included conspiracy to disarm members of the enemy forces, taking part in a punishment shooting, and the taking of ‘legally held’ shotguns.

Following a year on remand in Crumlin Road jail, Belfast, he was tried and sentenced to ten years in December 1977, immediately joining the blanket men in H3, and eventually finding himself sharing a cell with his Dungiven friend and comrade, Liam McCloskey, continuing to do so until he took part in the thirty-man four-day fast which coincided with the end of the original seven-man hunger strike last December.

LONG KESH

Since they were sentenced in 1977, both Dungiven men suffered their share of brutality from Crumlin Road and Long Kesh prison warders, Kevin being ‘put on the boards’ for periods of up to a fortnight, three or four times.

On Wednesday, April 26th, 1978, six warders, one carrying a hammer, came in to search their cell. Kevin’s bare foot, slipping on the urine-drenched cell floor, happened to splash the trouser leg of one of the warders, who first verbally abused him and then kicked urine at him.

When Kevin responded in like manner he was set upon by two warders who punched and kicked him, while another swung a hammer at him, but fortunately missed. The punching and kicking continued till Kevin collapsed on the urine-soaked floor with a bruised and swollen face.

In another assault by prison warders, Kevin’s cellmate, Liam McCloskey, suffered a burst ear-drum during a particularly bad beating, and is now permanently hard of hearing.

DETERMINATION

Even as long ago as April 1978, just after the ‘no wash’ protest had begun, Kevin was reported, in a bulletin issued by the Dungiven Relatives Action Committee, to “have lost a lot of weight, his face is a sickly white and he is underfed”.

His determination, and his sense of loyalty to his blanket comrades, saw him through, however, even the hardest times.

His former H-Block comrade, Eunan Brolly, who was also in H3 before his release, remembers how Kevin once put up with raging toothache for three weeks rather than come off the protest to get dental treatment. It was the sort of thing which forced some blanket men off the protest, at least temporarily, but not Kevin.

Eunan, who recalls how Kevin used to get a terrible slagging from other blanket men because the GAA, of which of course he was a member, did not give enough support to the fight for political status, also says he was not surprised by Kevin’s decision to join the hunger strike. Like other blanket men, Eunan says, Kevin used to discuss a hunger strike as a possibility, a long time ago, “and he was game enough for it”.

Neither were his family, who supported him in his decision, surprised: “Kevin’s the type of man”, said his father, when Kevin was on the hunger strike, “that wouldn’t lie back. He’d want to do his share.”

In the Free State elections, in June, Kevin stood as a candidate in the Waterford constituency, collecting 3,337 first preferences before being eliminated - after Labour Party and Fianna Fail candidates - on the fifth count, with 3,753 votes.

But the obvious popular support which the hunger strikers and their cause enjoyed nationally was not sufficient to elicit support from the Free State government who share the common, futile hope of the British government - the criminalisation of captured freedom fighters.

The direct consequence of that was Kevin’s death - the seventh at that stage - in the Long Kesh hospital at 1.00 a.m. on Saturday, August 1st after seventy-one days on hunger strike.

Mickey Devine - A typical Derry lad

Twenty-seven-year-old Micky Devine, from the Creggan in Derry city, was the third INLA Volunteer to join the H-Block hunger strike to the death.

Micky Devine took over as O/C of the INLA blanket men in March when the then O/C, Patsy O’Hara, joined the hunger strike but he retained this leadership post when he joined the hunger strike himself.

Known as ‘Red Micky’, his nickname stemmed from his ginger hair rather than his political complexion, although he was most definitely a republican socialist.

The story of Micky Devine is not one of a republican ‘super-hero’ but of a typical Derry lad whose family suffered all of the ills of sectarian and class discrimination inflicted upon the Catholic working-class of that city: poor housing, unemployment and lack of opportunity.

Micky himself had a rough life.

His father died when Micky was a young lad; he found his mother dead when he was only a teenager; married young, his marriage ended in separation; he underwent four years of suffering ‘on the blanket’ in the H-Blocks; and, finally, the torture of hunger-strike.

Unusually for a young Derry nationalist, because of his family’s tragic history (unconnected with ‘the troubles’), Micky was not part of an extended family, and his only close relatives were his sister Margaret, seven years his elder, and now aged 34, and her husband, Frank McCauley, aged 36.

CAMP

Michael James Devine was born on May 26th, 1954 in the Springtown camp, on the outskirts of Derry city, a former American army base from the Second World War, which Micky himself described as “the slum to end all slums”.

Hundreds of families - 99% (unemployed) Catholics, because of Derry corporation’s sectarian housing policy - lived, or rather existed, in huts, which were not kept in any decent state of repair by the corporation.

One of Micky’s earliest memories was of lying in a bed covered in old coats to keep the rain off the bed. His sister, Margaret, recalls that the huts were “okay” during the summer, but they leaked, and the rest of the year they were cold and damp.

Micky’s parents, Patrick and Elizabeth, both from Derry city, had got married in late 1945 shortly after the end of the Second World War, during which Patrick had served in the British merchant navy. He was a coalman by trade, but was unemployed for years.

At first Patrick and Elizabeth lived with the latter’s mother in Ardmore, a village near Derry, where Margaret was born in 1947. In early 1948 the family moved to Springtown where Micky was born in May 1954.

Although Springtown was meant to provide only temporary accommodation, official lethargy and sectarianism dictated that such inadequate housing was good enough for Catholics and it was not until the early ‘sixties that the camp was closed.

BLOW

During the ‘fifties, the Creggan was built as a new Catholic ghetto, but it was 1960 before the Devines got their new home in Creggan, on the Circular Road. Micky had an unremarkable, but reasonably happy childhood. He went to Holy Child primary school in Creggan.

At the age of eleven Micky started at St. Joseph’s secondary school in Creggan, which he was to attend until he was fifteen.

But soon the first sad blow befell him. On Christmas eve 1965, when Micky was aged only eleven, his father fell ill; and six weeks later, in February 1966, his father, who was only in his forties, died of leukaemia.

Micky had been very close to his father and his premature death left Micky heartbroken.

Five months later, in July 1966, his sister Margaret left home to get married, whilst Micky remained in the Devines’ Circular Road home with his mother and granny.

At school Micky was an average pupil, and had no notable interests.

STONING

The first civil rights march in Derry took place on October 5th, 1968, when the sectarian RUC batoned several hundred protesters at Duke Street. Recalling that day, Micky, who was then only fourteen wrote:

“Like every other young person in Derry my whole way of thinking was tossed upside down by the events of October 5th, 1968. I didn’t even know there was a civil rights march. I saw it on television.

“But that night I was down the town smashing shop windows and stoning the RUC. Overnight I developed an intense hatred of the RUC. As a child I had always known not to talk to them, or to have anything to do with them, but this was different

“Within a month everyone was a political activist. I had never had a political thought in my life, but now we talked of nothing else. I was by no means politically aware but the speed of events gave me a quick education.”

TENSION

After the infamous loyalist attack on civil rights marchers in nearby Burntollet, in January 1969, tension mounted in Derry through 1969 until the August 12th riots, when Orangemen - Apprentice Boys and the RUC - attacked the Bogside, meeting effective resistance, in the ‘Battle of the Bogside’. On two occasions in 1969 Micky ended up at the wrong end of an RUC baton, and consequently in hospital.

That summer Micky left school. Always keen to improve himself, he got a job as a shop assistant and over the next three years worked his way up the local ladder: from Hill’s furniture store on the Strand Road, to Sloan’s store in Shipquay Street, and finally to Austin’s furniture store in the Diamond (and one can get no higher in Derry, as a shop assistant).

British troops had arrived in August 1969, in the wake of the ‘Battle of the Bogside’. ‘Free Derry’ was maintained more by agreement with the British army than by physical force, but of course there were barricades, and Micky was one of the volunteers manning them with a hurley.

INVOLVED

At that time, and during 1970 and 1971, Micky became involved in the civil rights movement, and with the local (uniquely militant) Labour Party and the Young Socialists.

The already strained relationship between British troops and the nationalist people of Derry steadily deteriorated - reinforced by news from elsewhere, especially Belfast - culminating with the shooting dead by the British army of two unarmed civilians, Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie, in July of 1971, and with internment in August. Micky, by this time seventeen years of age, and also politically maturing, had joined the ‘Officials’, also known as the ‘Sticks’.

He became a member of the James Connolly ‘Republican Club’ and then, shortly after internment, a member of the Derry Brigade of the ‘Official IRA’.

‘Free Derry’ had become known by that name after the successful defence of the Bog side in August 1969, but it really became ‘Free Derry’, in the form of concrete barricades etc., from internment day. Micky was amongst those armed volunteers who manned the barricades

Typical of his selfless nature (another common characteristic of the hunger strikers), no task was too small for him.

He was ‘game’ to do any job, such as tidying up the office. Young men, naturally enough, wanted to stand out on the barricades with rifles: he did that too, but nothing was too menial for him, and he was always looking for jobs.

Bloody Sunday, January 30th, 1972, when British Paratroopers shot dead thirteen unarmed civil rights demonstrators in Derry (a fourteenth died later from wounds received), was a turning point for Micky. From then there was no turning back on his republican commitment and he gradually lost interest in his work, and he was to become a full-time political and military activist.

TRAUMA

Micky experienced the trauma of Bloody Sunday at first hand. He was on that fateful march with his brother-in-law, Frank, who recalls: “When the shooting started we ran, like everybody else, and when it was over we saw all the bodies being lifted.”

The slaughter confirmed to Micky that it was more than time to start shooting back. “How” he would ask, “can you sit back and watch while your own Derry men are shot down like dogs?”

Micky had written: “I will never forget standing in the Creggan chapel staring at the brown wooden boxes. We mourned, and Ireland mourned with us.

“That sight more than anything convinced me that there will never be peace in Ireland while Britain remains. When I looked at those coffins I developed a commitment to the republican cause that I have never lost.”

From around this time, until May when the ‘Official IRA’ leadership declared a unilateral ceasefire (unpopular with their Derry Volunteers), Micky was involved not only in defensive operations but in various gun attacks against British troops.

Micky’s commitment and courage had shone through, but no more so than in the case of scores of other Derry youths, flung into adulthood and warfare by a British army of occupation.

TRAGIC

In September, 1972, came the second tragic loss in Micky’s family life. He came home one day to find his mother dead on the settee with his granny unsuccessfully trying to revive her.

His mother had died of a brain tumour, totally unexpectedly, at the age of forty-five. Doctors said it had taken her just three minutes to die. Micky, then aged eighteen, suffered a tremendous shock from this blow, and it took him many months to come to terms with his grief.

Through 1973, Micky remained connected with the ‘Sticks’, although increasingly disillusioned by their openly reformist path. He came to refer to the ‘Sticks’ as “fireside republicans”, and was highly critical of them for not being active enough.

Towards the end of that year, Micky, then aged nineteen, got married. His wife, Margaret, was only seventeen. They lived in Ranmore Drive in Creggan and had two children: Michael, now aged seven and Louise, now aged five.

Micky and his wife had since separated.

In late 1974, virtually all the ‘Sticks’ in Derry, including Micky, joined the newly formed IRSP, as did some who had dropped out over the years. And Micky necessarily became a founder member of the PLA (People’s Liberation Army), formed to defend the IRSP from murderous attacks by their former comrades in the sticks.

In early 1975, Micky became a founder member of the INLA (Irish National Liberation Army) formed for offensive operational purposes out of the PLA.

The months ahead were bad times for the IRSP, relatively isolated, and to suffer a strength-sapping split when Bernadette McAliskey left, taking with her a number of activists who formed the ISP (Independent Socialist Party), since deceased.

They were also difficult months for the fledgling INLA, suffering from a crippling lack of weaponry and funds. Weakness which led them into raids for both as their primary actions, and rendered them almost unable to operate against the Brits.

Micky was eventually arrested on the Creggan. In the evening of September 20th, 1976, after an arms raid earlier that day on a private weaponry, in Lifford, County Donegal, from which the INLA commandeered several rifles and shotguns, and three thousand rounds of ammunition.

ARRESTED

Micky was arrested with Desmond Walmsley from Shantallow, and John Cassidy from Rosemount. Along on the operation, though never convicted for it, was the late Patsy O’Hara, with whom Micky used to knock around as a friend and comrade.

Micky was held and interrogated for three days in Derry’s Stand Road barracks, before being transported in Crumlin Road jail in Belfast where he spent nine months on remand.

He was sentenced to twelve years imprisonment on June 20th, 1977, and immediately embarked on the blanket protest. He was in H5-Block until March of this year when the hunger strike began and when the ‘no-wash, no slop-out’ protest ended, whereupon he was moved with others in his wing to H6-Block.

Like others incarcerated within the H-Blocks, suffering daily abuse and inhuman and degrading treatment, Micky realised - soon after he joined the blanket protest - that eventually it would come to a hunger strike, and, for him, the sooner the better. He was determined that when that ultimate step was reached he would be among those to hunger strike.

SEVENTH

On Sunday, June 21st, this year, he completed his fourth year on the blanket, and the following day he joined Joe McDonnell, Kieran Doherty, Kevin Lynch, Martin Hurson, Thomas McElwee and Paddy Quinn on hunger strike.

He became the seventh man in a weekly build-up from a four-strong hunger strike team to eight-strong. He was moved to the prison hospital on Wednesday, July 15th, his twenty fourth day on hunger strike.

With the 50 % remission available to conforming prisoners, Micky would have been due out of jail next September.

As it was, because of his principled republican rejection of the criminal tag he chose to fight and face death.

Micky died at 7.50 am on Thursday, August 20th, as nationalist voters in Fermanagh/South Tyrone were beginning to make their way to the polling booths to elect Owen Carron, a member of parliament for the constituency, in a demonstration - for the second time in less than five months - of their support for the prisoners’ demands.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)