By Danny Morrison (for the Guardian)

I last saw Bobby Sands alive in December 1980. He had long greasy hair and a matted beard as a result of the no-wash prisoners’ protest. He had spent a third of his 27 years behind bars. At the end of the visit I was banned from the prison. I next saw him in his coffin, after his death exactly 30 years ago, before 100,000 people gathered for his funeral in Belfast. By then he’d spearheaded the hunger strike campaign for political status for IRA prisoners – and in the process gained massive international recognition after being elected an MP.

I last saw Bobby Sands alive in December 1980. He had long greasy hair and a matted beard as a result of the no-wash prisoners’ protest. He had spent a third of his 27 years behind bars. At the end of the visit I was banned from the prison. I next saw him in his coffin, after his death exactly 30 years ago, before 100,000 people gathered for his funeral in Belfast. By then he’d spearheaded the hunger strike campaign for political status for IRA prisoners – and in the process gained massive international recognition after being elected an MP.

When I first saw him it was a freezing wintry night in hut 17, Long Kesh prison. It was 1973 and he was 18 years old.

I, like 2,000 others around that time, had been interned – neither charged nor sentenced. We were in Long Kesh as a result of what happened in 1969, when the unionist government had suppressed the nationalists’ civil rights movement and triggered major civil strife. The British army, sent in as “peacekeepers”, turned out to be even greater oppressors. As a result, the IRA’s call to arms seemed the solution. Bobby was imprisoned for possession of four handguns and was treated as a prisoner of war. It was while in Long Kesh that the famous smiling photograph of him, which was to become iconic, was taken.

Released in 1976, he was at liberty for a year and when I met him he was full of enthusiasm about setting up a tenants’ association in Twinbrook where he lived. Months later he was arrested on active service and was sentenced to 14 years for possessing one handgun.

But now he was sent to the H-blocks – really just an extension of Long Kesh – because the government had withdrawn “special category status” in an attempt to criminalise the prisoners and the cause of Irish freedom. Here he joined hundreds of others on the “blanket protest” – refusing to wear a prison uniform and call warders “sir”. He was beaten regularly and was often in solitary confinement, punished with a bread and water diet (ruled illegal by the European court). After visiting the H-blocks, the Catholic archbishop Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich compared the conditions to “the sewer pipes in the slums of Calcutta”.

Bobby wrote to me in smuggled letters, sending me his poetry and short stories which I published. Throughout 1980 I visited him weekly as frantic attempts were made to avoid a hunger strike. He had one of the sharpest intellects I have ever come across. In 1981 he and nine comrades could no longer watch the younger prisoners being beaten and felt that they had no option but to hunger strike to the death, to establish in the eyes of the world that they were political prisoners fighting a just cause.

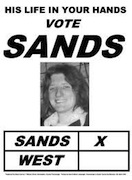

Margaret Thatcher, then prime minister, had said: “How can I talk to them [the prisoners] when they have no support, no mandate?” Yet when Bobby Sands was elected by the people of Fermanagh and South Tyrone, with more votes than Thatcher in Finchley, she became even more intransigent. She refused to negotiate and changed the law to prevent any other prisoner standing for election.

Over a period of seven months nine other men followed Bobby, dying on a hunger strike that Thatcher described as “the IRA’s last card”. How wrong she was. Recruits flocked to the IRA. Its support multiplied. Its operations intensified. Later that year, speaking at Sinn Féin’s annual conference, I used the phrase “the Armalite and the ballot box” to sum up the new duel strategy of engaging in armed struggle and simultaneously contesting elections.

Bobby Sands’s election was undoubtedly the springboard for Sinn Féin’s subsequent successes, which have seen it emerge as the largest party in the north of Ireland, with the former IRA commander Martin McGuinness as joint first minister, and Gerry Adams becoming the leader of 14 TDs in the Republic’s Dáil Éireann.

After the hunger strike, the British government recognised the political status of the prisoners and eventually granted their early release under the 1998 Good Friday agreement. Had such an agreement been signed back in 1969, not one of the thousands who died in the conflict would have lost their lives.

Songs have been written about Bobby Sands, films made, streets named after him. He was a poet, a revolutionary, and – in the words of singer Christy Moore – the “People’s Own MP”.

His and his comrades’ sacrifices energised and inspired republicans. Bobby spoke of revenge not in terms of one side triumphing over another but said: “Our revenge will be the laughter of our children.” Rather than diminishing over the passage of time, the stature of Bobby Sands in history has only increased.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)