By Jim Gibney (for Irish News)

On Easter Sunday all over Ireland, republicans gather in tribute to those who died in Ireland’s struggle for independence. This Easter republicans have much to be proud of and much to be concerned about.

The long worked-for breakthrough in the election to the Dail recently has put Sinn Fein at the centre of southern politics in a way only dreamed off a few short years ago.

Sinn Fein’s considerable presence in the north’s executive and assembly is a demonstration of how much progress is being made to making the north a democratic society based on the principles of equality, diversity and inclusiveness.

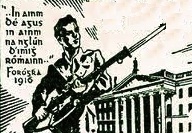

Gerry Adams’s presence as the party’s leader in the Dail and Martin McGuinness’s presence as joint first minister in the executive symbolises for republicans and nationalists the unification of this country’s two states. This symbolism is extremely important to the republican constituency that Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness represent because it is the same constituency which produced the men and women who occupied Dublin’s General Po st Office on Easter Monday 1916, 95 years ago.

It was out of that constituency and the political and actual rubble left behind after the rising of Easter week that the republican leaders of pre and post-partitioned Ireland emerged. The same constituency produced those who fought the War of Independence, the Civil War,who set up the southern state, who died in its prisons and who in the six counties kept the flame of republican resistance alight in the lean years, and who led the IRA’s armed resistance between 1970 and the end of the IRA’s campaign.

The people who inhabit this constituency were and are formidable individuals, of that there is no doubt. They are not pacifists nor are they war-mongers. When war was the only option they fought it and paid a heavy price for doing so, as did the civilian population and those in the British Crown forces. And when a peaceful alternative to war became an option they embraced it. In doing so they did not depart from the vision outlined in the Proclamation of 1916 which republicans remain dedicated to and which will be read out at Easter commemorations. Much welcome change has occurred in Irish society as a result of the peace process but there are issues yet to be finally resolved. These are related to the conflict - legacy issues, if you like, such as: the truth for the relatives of those killed duringthe conflict; an amnesty for political prisoners with all that that entails; and state recognition of nationalist emblems.

I also believe that the existence of armed republicans is another legacy issue - a legacy of Britain’s involvement in Ireland and a legacy of the use by republicans of armed struggle.

Their activities are misguided and are creating heartache not only for the families of those being targeted for attack but also for their own families and those in jail as a result of their activities. And although this misery exists on the margins of the new Irish society it echoes disturbingly with our recent past. Those involved in helping to end the IRA’s campaign must involve themselves in helping to end these armed activities with similar patience and determination.

Republicans are steadily pursuing the objectives outlined in the 1916 Proclamation and are doing so in challenging times for the Irish people. The challenges are different to those faced by Padraig Pearse and James Connolly in 1916 because Ireland, although still dealing with the impact of its colonial past, is a pluralist,modern democracy.

The biggest challenge of all is tochart a course out of the economic crisis that has engulfed the southern state and isimpacting daily on the lives of people in the north.

This can best be done by republicans drawing off the Proclamation’s commitment to social and economic justice andwinning over more people to the need for a different society - one that is not based obsessively onmaterialism but on the Proclamation’s vision of “the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland, and the unfettered control of Irish destinies”. Belief in that creed would have prevented the greedy bankers from bankrupting the southern state.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)