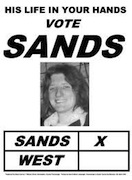

Sinn Fein’s electoral strategy began 30 years ago during the 1981 hunger strikes. Since those painful days and emotional election victories -- beginning with Bobby Sands’s historic win in Fermanagh/South Tyrone, 30 years ago this week, the North now faces three elections -- on May 5, the anniversary of Bobby Sands’s death.

We reprint the reflections form 1998 of some senior republicans on the terrible prison struggle which gave birth to their electoral strategy.

Owen Carron

As Principal of a remote rural school life has come “full circle” for Owen Carron, at least in a private sense. In 1981, Owen was a primary school teacher when fate unexpectedly plucked him from obscurity and thrust him into the forefront of a political struggle. Today, sitting amidst the 17 pupils of Drumnamore School, Owen remembers the moment which turned his life upside down as a pivotal moment in the continuing dynamic towards Irish reunification and democracy.

“If Frank Maguire hadn’t died, if he had died a few months earlier or a few months later,” says Owen, “history would be different, I’m convinced of that.” The by-election prompted by the sudden death of the sitting MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone, called as Bobby Sands’ hunger strike approached crisis point, was seized upon as an opportunity to save his life.

“We thought we could save him,” says Owen, “we thought if we could get Bobby elected, the British couldn’t just let him die.”

As his election agent, Owen secured regular access to Bobby Sands during the last few weeks of his life. “I don’t think Bobby was ever naive about his chances of survival. I remember him as unwavering, committed and very focused. I think he knew the Brits would let him die.”

The decision to stand Bobby Sands as a candidate was taken at a time when even the idea of standing a Republican as a candidate, let alone an imprisoned IRA Volunteer, was anathema to the Republican movement. Developing an election strategy required “a leap of faith”, says Owen. “For some Republicans it was a leap they initially couldn’t quite make.”

Sinn Fein’s election strategy was born in the front room of a tiny house in Enniskillen. Denied access to the town’s commercial premises, Maud Drumm offered Sinn Fein the use of her parlour as an election headquarters.

The labour was short (there were only ten days in the run up to the election), intense (as republicans flocked into the area to assist the campaign) and at times painful (as disagreements within the party were slowly resolved). The delivery was euphoric. Danny Morrison was roaring and shouting. The hall was in uproar as the electoral officer announced Bobby’s election victory,” says Owen, “it was a victory but it didn’t save his life.” Bobby Sands’ death less than three weeks later was a “bitter pill”.

Retrospectively Owen sees the election of Bobby Sands as a watershed in the current phase of the struggle. Within Republicanism it was a decisive break with the past, it overcame the movement’s psychological fear of electoral defeat, and it demonstrated the power of popular mobilisation around Republican demands, says Owen. “In time I think we’ll look back and identify the struggle around political status and the subsequent election of Bobby Sands as a defining moment in the struggle against British rule in Ireland. Since 1981 Sinn Fein’s electoral strategy has developed from strength to strength. Thatcher’s criminalisation strategy never recovered and subsequent British governments continue to pay the price of that defeat.”

Mary Nelis

When Mary Nelis says she remembers the first visit with her son Donnacha after he was sentenced to sixteen years imprisonment, “as if it were yesterday”, the blink of tears in her eyes confirms that she is speaking quite literally.

It began with a telephone call from a Catholic priest. Sentenced just two months after Ciaran Nugent, Mary’s son Donnacha was one of a handful of protesting Republican prisoners jailed immediately after the removal of Political Status. Prisoners refusing to wear a uniform were not only left naked and confined to their cells, they were also denied contact with their families. Donnacha was barely eighteen and no one had seen him for months. “Fr Cahal told me he hadn’t been allowed to see Donnacha and the other protesting prisoners, other prisoners were worried because they hadn’t seen any of them either.”

The priest’s worst fears were later confirmed. Donnacha was brought before him naked, he was badly bruised from head to toe with what appeared to be cigarette burns to his back. As a mother she must do something, Fr. Cahal told Mary. It was an act of desperation but one which would be repeated by Mary, and many other mothers, wives and sisters, thousands of times in towns and cities throughout Ireland, Europe and America during five years of intense political campaigning. For women who had previously lived all their lives within the modest confines of home and church, it was an act of great personal courage which transformed their relationships both within the family and with the Catholic heirarchy.

“There were three of us,” says Mary, “we took off all our clothes, wrapped ourselves in a blanket and called a taxi.” As Derry’s Cathedral bells rang out in support of a rally organised by the Peace People, the three women protested at the chapel gates. “My son is lying naked in a cell. Do you care?” read Mary’s placard. And at first it seemed as if very few people cared.

Looking back, Mary sees the key lessons to be drawn from that period as the “long hard haul” of building mass support around a political issue and strategic flexibility which allowed the Republican campaign for political status to align with the humanitarian agenda of five just demands.

Mobilisation was door to door, street by street, village, town, city. The campaign took Mary throughout Ireland, across Europe and to the United States. “There were no short cuts,” says Mary. “For months at a time we thought we were making no headway. There was a wall of silence surrounding the protest in the jails, it was demolished brick by brick.”

Bik McFarlane

Travel anywhere in Ireland with Bik McFarlane and there will be people there eager to greet him. The publication of `comms’ (communications written on tissue paper and smuggled out of the jail) written by Bik as OC during the hungerstrikes remain the most poignant testimony of the unfolding tragedy in which ten men lost their lives.

In the tenderness of a note written immediately after the death of Bobby Sands from “Bik to Brownie”, the personal and political are inextricably intertwined. In itself this tells us more about the struggle in the H Blocks than many thousands of words of annalysis written retrospectively.

When Bik’s words recently appeared painted two storeys high on a gable wall in Dublin city, it seemed wholly appropriate. Bik McFarlane belongs where the private and public domains collide. We may not know him personally but our knowledge of him is personal. No wonder he evokes the affection of strangers.

“Nothing in the history of the Anglo-Irish conflict has ever been conceded by the British or attained by the Irish without recourse to long, arduous and often bitter struggle,” says Bik, “the hungerstrike of 1981 was no exception.”

Bik McFarlane has spent more than half of his adult life imprisoned by the British. In over two decades, he has known only three short years of relative freedom. Bik was one of 38 Republican prisoners to escape from the H Blocks of Long Kesh in the Great Escape of 1983. He was recaptured in Amsterdam in 1986. Only recently released after serving a life sentence, Bik’s future still remains uncertain. On the day he was officially released on license by the British, Bik was arrested by the Garda in Dundalk. He is currently signing bail.

The implementation of the British government’s criminalisation policy in the late 1970s became a living reality for Bik McFarlane one April morning in 1978. Bik was “on the boards” in the punishment block following an escape attempt when he was told his `special category status’ had been withdrawn by the NIO. Instead of returning to the cages Bik was trailed into the Blocks. The no-wash protest had begun a month earlier. He was naked and the wing stank. The transition from political prisoner to the brutality of criminalisation had taken less than five minutes, the time it took to cross from Cage 12 to H3.

“The British government intended the H Blocks to be the `breakers’ yard’ for the Republican Movement,” says Bik. “They saw prisoners as the most vulnerable section of the movement and they set out to break them.”

Naked in a prison cell, vulnerable, isolated and subjected to a brutal prison regime, the British imagined the prisoners had been stripped of all means of resistance. They were wrong. In what still remains one of the most remarkable stories of human endeavour, the prisoners organised and maintained a collective campaign of defiance.

“The maturity of the prisoners’ analysis underpinned their ability to resist,” says Bik. “We were confronting a prison regime but we were exposing British rule in Ireland.”

CHRONOLOGY

March 1976: British end `Special Category Status’.

September 1976: The first Republican prisoner sentenced after the removal of political status refuses to wear a prison uniform. Ciaran Nugent is left naked with only a blanket. In the next five years over 1000 men in the H blocks and 30 women in Armagh will participate in the protest.

March 1978: Increased brutality and harassment by prison wardens escalates into a no-wash protest.

October 1980: Seven protesting H Block prisoners go on hungerstrike. They are later joined on hunger strike by three women in Armagh jail.

December 1980: The British present prisoners with a document which appears to offer a resolution to the crisis. First hunger strike ends.

January 1981: The ending of the no-wash protest by a section of the prisoners, as a gesture of good faith, is met by British intransigence on the clothing issue.

February 1981: A second hunger strike is announced in a joint statement by the blanketmen and women of Armagh.

March 1981: Bobby Sands begins his hunger strike as thousands of nationalists take to the streets of Belfast to demonstrate their support. The no-wash protest ends. Within a fortnight Bobby is joined on hunger strike by Francie Hughes. A week later Raymond McCreesh and Patsy O’Hara begin their hunger strike.

April 1981: Bobby Sands is elected as MP with almost 30,500 votes in a by-election in Fermanagh/South Tyrone. Paul Whitters from Derry is shot dead by a plastic bullet.

May 1981: The death of Bobby Sands prompts widespread rioting in nationalist areas. Tens of thousands of mourners attend Bobby’s funeral. A week later a second hunger striker, Francie Hughes dies. Within five days two more hunger strikers lose their lives. Patsy O’Hara dies just a few hours after Raymond McCreesh. In Belfast Julie Livingstone (14) and Carol Ann Kelly (12), and in Derry, Harry Duffy, are shot dead by plastic bullets. IRA Volunteers George McBrearty and Charlie Maguire are killed on active service.

June 1981: The struggle is further endorsed as tens of thousands of nationalists vote in the 26 Counties general election in support of the prisoners’ demands. Hunger striker Kieran Doherty is elected TD for Cavan/Monaghan and blanketman Paddy Agnew is elected TD for Louth.

July 1981: Fifth hunger striker, Joe McDonnell, dies. Within hours of Joe’s death, a member of the Fianna, John Dempsey (16) is shot dead by the British army in West Belfast, Nora McCabe (29) is fatally wounded by a plastic bullet and Danny Barret (15) is shot dead by the British army in North Belfast. Sixth hunger striker Martin Hurson dies.

August 1981: Seventh hunger striker, Kevin Lynch dies swiftly followed by hunger stiker Kevin Doherty who dies a day later. Within a week another hunger striker, Thomas McElwee dies. Liam Canning from West Belfast is murdered by loyalists. In North Belfast Peter Magennis is shot dead by a plastic bullet. Tenth hunger striker, Mickey Devine dies as Bobby Sands’s election agent Owen Carron is elected MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone.

September 1981: Ending the hunger strike becomes inevitable as families begin to authorise medical intervention as more hunger strikers become critical.

October 1981: After 217 days of consecutive hunger strike involving 23 hunger strikers, many reaching the brink of death and ten dying, protesting prisoners announce an end to the hunger strike. Within weeks the blanket protest also ends as Republicans develop an alternative strategy of subversion which will eventually secure all their five demands and leads directly into the Great Escape of 1983.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)