On March 1 1981 Raymond McCartney was a republican prisoner in Long Kesh when the second hunger strike began.

The Derry prisoner knew more than most of the difficulties that lay ahead for Bobby Sands as he was still recovering from the first hunger strike, where he went without food for 53 days.

The 1981 hunger strike was the culmination of almost five years of protests by republican prisoners in the H Blocks. The prisoners said they were involved in a political conflict and wanted to be treated as political prisoners while the British Government and prison authorities insisted they were criminals.

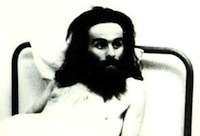

The protesting prisoners refused to wear prison uniform and did not co-operate with the prison regime. They held a ‘no-wash’ protest and refused to ‘slop out’ and instead smeared their excrement on the walls of their cells - leading to this stage of the dispute being dubbed the ‘dirty protest.’

In October 1980, seven prisoners, including Raymond McCartney, began a hunger strike in a bid to have special category status restored. Their protest fast ended in December as Sean McKenna neared death and the strike leaders thought they had secured commitments from the British Government. However, these commitments were reneged upon and the stage was set for a second hunger strike.

The hunger strike which began 30 years ago today was led by Belfast republican Bobby Sands who said the republican prisoners had five demands; the right not to wear prison uniform, the right not to do prison work, the right of free association with other prisoners and to organise recreation and educational pursuits, the right to have one visit and parcel a week, and full restoration of remission.

Looking back on that day, Mr McCartney said he, like other prisoners, hoped no one would have to die in the hunger strike. “There was a betrayal by the British Government at the end of the first hunger strike over clothes. This time it was clear. It was about recognition of our status as political prisoners. The prison authorities had the opportunity to do the right thing at the end of the first hunger strike and we acted with good faith but they did not and that left a large gap that had to be filled and Bobby Sands knew how to do that.

“The rest of us were living in hope that no one would have to die. On reflection now, it is plain to see that Bobby Sands was in no doubt that he was going to die. He knew the only way that people were going to accept that we were involved in a political struggle was by going on hunger strike and dying. It was a measure of his leadership and raw courage,” he said.

While the ten republicans who died on hunger strike in Long Kesh in 1981 have now become republican icons, Mr McCartney explains that to him they were friends and comrades. “The ten who died were all personal friends and people I knew well.

“I saw Bobby the Saturday before he began his hunger strike and had a few words with him. They were all comrades. There was a great sense of that in the prison at the time,” he explained.

The Foyle MLA also said the mood had changed between the first and second hunger strikes. “There is no doubt that the British Government felt we had taken it as far as we could.

“They thought they had us outmanoeuvred. Also, while the first hunger strike had a degree of public sympathy from people who weren’t republican, we were not sure that would be repeated,” he explained.

Mr McCartney also said he viewed the second hunger strike as a continuation of the first. “On a personal level, to me the second hunger strike was very emotional. Irrespective of how the first hunger strike ended, as someone who had taken part in it I felt like someone had thrown the ball to me and, through no fault of my own, I didn’t catch it. Someone else had to pick it up and carry it on and that is what Bobby and the others did.

“Perhaps I, more than most, really hoped that no one would die. I knew that each of my comrades who went on the second hunger strike did so with a sense of comradeship.

“They did it for all of us as republicans, particularly for republican prisoners, but I felt they were doing it for us who took part in the first hunger strike too,” he said.

Mr McCartney also said Bobby Sands’ election as an MP brought hope that the hunger strike would end without anyone dying. “No one expected the death of Frank Maguire. One of the things I reflect on when I look back at the hunger strikes is that sometimes people make decisions that just catch you cold. When people like Jim Gibney first said that Bobby should stand in the election many thought it was madness. It was alien to republicans at the time. People were saying he had no chance and Thatcher herself was raising the stakes.

“Even right up until the election result was announced, no one was sure he was going to win. When the result came though we heard it on a smuggled radio and we had been told not to make any noise or the radio would be discovered. I can only describe my reaction at the time as silent screaming. We were elated.”

The Derry man said the decision to contest the election changed his way of thinking. “It showed me that the decisions we make today have implications for the future. We have to be mindful of the past but not held by it. That is a lesson I have taken with me since the hunger strikes,” he said.

The MLA said the deaths of the hunger strikers changed the course of Irish history. “A each of our comrades died there was a great sense of loss.

“We were a very close group of people. The intensity of it was felt more on the outside. 60 people died on the streets.

“When the hunger strike ended there was a sense of relief, mixed with great loss.

“The focus was shifted on to the families and they made the correct decision to end it. A clear message went around the world that the ten lads who died on hunger strike were involved in a political struggle and, through their deaths, the world acknowledged and accepted that.”

Paying tribute to those who died, Mr McCartney said; “On a human level it is a remarkable story.

“Ten young lads laid down their lives for the rest of us. It had a major impact on republican history and Irish history and our relationship with Britain.

“People often ask me now if it was worth it. I say with absolute certainty that it was the right thing to do at the time. If the same conditions prevailed today it would still be the right thing to do,” he said.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)