The emergence of the hunger strike protest in 1980 and the degree to which all sides were unprepared to deal with it are the dominant features of the historical papers which were released over the New Year.

The release of some previously classified papers dating from 30 years ago is an annual tradition observed by the governments in Dublin and London.

While it is clear that many controversial papers were withheld, a number of those released at the weekend reveal new insights into the Haughey-Thatcher diplomacy and the first hunger strike protest at Long Kesh prison in 1980.

The British government’s attitude towards then Taoiseach Charles Haughey and his efforts to establish closer political relations with Margaret Thatcher are highlighted in newly released files.

The aim of the British was “to keep Mr Haughey sweet” to ensure the Dublin government continued to co-operate with the British against the IRA, while dissuading his government from “unhelpful” political interventions in the North, the files reveal.

Haughey was seen as a more nationalistic Fianna Fail leader and Taoiseach than his predecessor, Jack Lynch.

On January 16th, 1980, the British ambassador in Dublin, Robin Haydon, warned that Haughey “is no friend of ours” and Britain “must expect a more nationalistic, republican approach to the overall question of unity”.

Nevertheless, British officials urged Margaret Thatcher to adopt a softly-softly approach to Charles Haughey in 1980, encouraging him to act the statesman with talk about a “special relationship” between the two governments in return for valuable assistance in military and policing matters.

Following a half-hour meeting with Haughey in late March, Haydon claimed the taoiseach felt “apprehensive” about Thatcher, “for whom he has respect (though he has not met her) because of her reputation in the media for toughness, decisiveness and determination”.

Hayden suggested Haughey had “a guilty or inferiority complex about his shady past - and present (!) - and wants to be accepted by us”.

THE PROBLEM OF HOPE

Records of Dublin cabinet meetings, meanwhile, showed Haughey was intent on ending Lynch’s “non-policy” on the North.

He told his fellow minister that that “we should declare the espousal by Britain of a new position on eventual Irish unity to be our principal objective”. He reckoned his proposal would “offer some hope, otherwise there would be no peace”.

However, this was seen as too radical a change for some cabinet ministers, particularly Brian Lenihan Snr.

On May 7th, Willie Whitelaw, the home secretary and former secretary of state for Northern Ireland, wrote to Thatcher saying: “The Taoiseach represents a problem.” He could not “have what he wants on Irish unity” due to the way this would destabilise the North. On the other hand, however, the British were eager to maintain what they saw as much improved ‘security’ co-operation against the Provisional IRA.

“All the signs are that the Garda have been instructed to pursue PIRA vigorously and to co-operate fully with the RUC, the Security Service and the Metropolitan Police.” Haughey’s “marginally firmer stance on Irish unity [was] a small price to pay for this”.

PRISON STRUGGLE

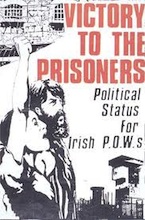

Towards the end of the year, the planned hunger strike of republican prisoners at Long Kesh - against the phasing out of their “special category” as prisoners - which began on October 27th, increased a sense of uneasiness in relations between Dublin and London.

In a brief meeting with Haughey in Luxembourg on December 1st, ahead of a full Anglo-Irish summit, Thatcher acknowledged that her forthcoming visit to Dublin was likely “to take place in circumstances which had not been foreseen when it was arranged”.

Haughey confirmed that the Dublin government was “enormously worried” by the hunger strike. The hunger strike “might enable the PIRA to mobilise support in a way they had been unable to do for several years”, British officials reported.

The leadership of the Provisional IRA itself was deeply uncomfortable about the hunger strike of 1980 and felt it risked undermining its attempts to revive its flagging campaign, according to British government documents.

The hunger strike “comes from PIRA’s weakness, not its strength”, claimed an intelligence report, from a “sensitive source” and shown to Margaret Thatcher on November 7th. “All the signs throughout the year have been that they were a declining force,” claimed the report.

“Operations have been thwarted, key figures arrested; they have made no progress to any of their objectives, short or long term; and have become increasingly alienated from the community. The leadership clearly regarded it as essential this winter to re-establish their credentials by stepping up the level of terrorist activity.”

The IRA’s capacity to mount a sustained campaign was still severely limited by a combination of improved security measures and war-weariness.

“1980 is not 1969 or 1972. The population as a whole is deeply weary of violence and unconvinced that it can achieve anything: the security forces are much better equipped and able to cope with street or sectarian violence.”

Far from being initiated by the leadership, the announcement of the hunger strike had “interfered seriously with their plans and is deeply disliked by the leadership for it confuses the issue, gives scope for division of views, and damaging disagreement, and is outside their control”.

It was, of course, still “possible to see the situation work to their advantage”.

Nonetheless, London calculated that the IRA leadership wanted “off the hook” on the issue and would be willing to settle for concessions stopping short of full political status for prisoners.

Inside Long Kesh, it was also reported that “the resolve of the strikers was being stiffened by the PIRA leader within the Maze named [Bobby] Sands who seemed a very determined character”. Significantly though, it was felt that Sands “did not appear to be acting in accordance with the directions of the IRA leadership outside the prison”.

This made it harder to find a “face-saving formula which would offer the hunger strikers an escape route”.

Previously unseen documents also describe a visit by Danny Morrison, Sinn Fein’s publicity director, on Saturday December 13th, permission for which had been specially granted by the authorities.

It was reported that hunger strikers felt that Morrison and the other intermediaries, such as John Hume, were “being taken for a ride by the Brits” and had wrung nothing out of the government. Bobby Sands reportedly told Morrison the prison was “about to explode”.

Morrison also tried to plead with Brendan Hughes, leader of the current hunger strike, to “be patient for a little longer”. In response, Hughes “lost his temper and threw Morrison out, throwing a food tray at him in the process”. After the meeting, Morrison confided in John Hume that “he thought his role as a carrier of messages was now at an end”, though he later became Bobby Sands’s spokesman in 1981.

Following the meeting, Sands asked for a meeting the next day with Bernadette McAliskey, a leading figure in the Smash H Block Campaign, and another senior republican figure whose name has been censored on the documents released at the National Archives in London.

Northern secretary Humphrey Atkins refused the meeting “on the basis of public reaction if such a terrorist ‘Council of War’ were permitted”.

It was also claimed that John Hume warned the government that such a meeting would draw it further into negotiations with leadership figures from the Provisionals, thereby according the prisoners political status by default.

The name of the individual whose identity is censored appears a number of times in the document but it is clear that he or she is a top-level figure in the republican movement, with a leadership position. Dermot Nally, the influential secretary to the Dublin government believed that this individual “could be useful” in the search for a solution, particularly as the leadership of the Provisionals was “opposed to the strike”.

The identity of this individual remains classified.

Following the end of the 1980 hunger strike, however, the year ended as it began, with Britain’s military strategy remaining at the fore in London, and British officials placing the emphasis on full security co-operation with Dublin in combination with the least possible cross-border political activity.

USA OPPOSED

In both Dublin and London, meanwhile, considerable efforts were directed to countering the influence of Irish-America, particularly a list of “unclean” political leaders held by the controversial 26-County Ambassador to Washington, Sean Donlon.

The need for US congressional approval for the controversial sale of American arms to the PSNI (then RUC) police was a significant issue in the early part of the year.

In his letter to the British government, a British embassy official warned of “the rumpus which Congressman [Mario] Biaggi and his supporters could be expected to provoke if it got out that export licences for the guns were likely to be approved”.

Biaggi, although a prominent ally of Carter, was hated by Donlon, who described him as a “minor opportunist with a discreditable past” because of his contacts with Sinn Fein and Noraid. However, house speaker Tipp O’Neill was lauded by Donlon for being close to his own and SDLP thinking.

Donlon explained the emphasis on O’Neill by describing his determination “not to muddy the channel of communication to the White House by dealing with unclean politicians and organisations”.

Haughey briefly attempted to shift Donlon from the Washington embassy but backed down in the face of political pressure from Senator Ted Kennedy and others.

UDA SUPPORT

Haughey later received the approval of the UDA for his stance on arms and against the IRA.

Andy Tyrie, Ulster Defence Association chief, personally wrote to the Taoiseach in December 1980 to thank him for his efforts to prevent arms crossing the border to the IRA, which he said had helped ensure loyalist death squads would not target Dublin.

“I am sure you realise that by seeking out and preventing the incessant flow of weapons and explosives into Ulster, you are effectively ensuring that Loyalist organisations will not seek vengeance in the Republic,” the UDA chief wrote.

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)