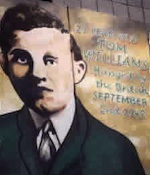

IRA Volunteer Tom Williams was hanged at age 19 by the British in September 1942, 68 years ago this month, for his part in a gun battle with the RUC which left one RUC man dead.

“If the history of this small island were compared to a rich tapestry, then Tom Williams’ story would only be the faintest of threads. Yet it is a remarkable story and deserves to be told.”

The following are extracts from ‘Executed: Tom Williams and the IRA’, by Jim McVeigh.

Boyhood

Thomas Joseph Williams was born in number 6 Amcomri Street in the Beechmount area of Belfast on the 12th May 1923. This was a year of pogroms. Through 1920, 1921, 1922 and into 1923, small Catholic enclaves right across Belfast came under vicious attack from rampaging Orange mobs, sometimes with the support of the new forces of the state. Before moving to Beechmount, Tom’s family had fled the small Catholic enclave in the Shore Road area of Belfast after their houses were attacked and burnt.

Tom’s uncle, Terry Williams had been jailed for helping to defend the Shore Road area from sectarian attack and from his earliest age Tom grew up hearing these stories of persecution and resistance. But this was more than folklore - discrimination and sectarian violence continued to be a daily reality for Catholics in the northern state.

Tom was the third child of a family of six. His brother Richard was the eldest, followed by Mary, who died of meningitis at the age of three. Tom was next and then baby Sheila, who died shortly after birth. Indeed Tom’s mother Mary died shortly after giving birth to Sheila at the young age of 29, leaving Tom in the care of his father, Thomas. Life was hard and early death commonplace at that time, especially among children.

Tom, who was still only a toddler, and his brother Richard went to live with their Granny Fay at 46 Bombay Street in the Clonard area of Belfast. A great bond of love and affection was to develop between Tom and his granny and it was upon her knee and in this small district that he began to learn of the struggle for Irish independence.

As soon as he was old enough, Tom joined Na Fianna Eireann, the republican scout organisation founded by Countess Markievicz in 1909, becoming a member of the Con Culbert slua in the Clonard area. Alfie Hannaway, a boyhood friend of Tom’s and his OC in Na Fianna, remembers appointing Tom to the rank of Quarter Master for the Company.

The C Company slua, which comprised over 30 boys from the district, spent much of their time drilling, in fitness activities and on occasion scouting for the IRA.

Manhood

For most working class Catholics, discrimination meant that employment opportunities were limited, and Tom was only able to find work as a message boy and as a labourer. He worked for a period in Greeves’ mill and even found work in the Docks area in the aircraft factory there.

In the months before his arrest, he worked in a printing firm. Almost everywhere he worked his sincere and friendly personality as well as his willingness to work hard, endeared him to his workmates and employers. These were qualities which would impress almost all who met him.

As soon as he was of age, Tom joined the IRA and at 17 became a Volunteer in C Company in the Clonard area where he lived. At the time, C Company’s area of command ran the length of the Lower Springfield Road, along the Falls Road from Beechmount to Conway Street, encompassing the streets in between. By the time Tom joined the IRA in 1940, it was already two years into its campaign and feeling the effects of arrests on both sides of the border.

Like most other young Volunteers, Tom was an enthusiastic supporter of this campaign and was probably ignorant of the growing difficulties the IRA leadership were facing. When Britain declared war on Germany on Sunday 3 September 1939, many republicans, including the young Tom, believed that the war presented the IRA with an opportunity to strike.

Tom was soon appointed Adjutant of C Company and in the months before his final arrest, at the young age of 18, he became the officer Commanding. In 1942 C Company had seven Sections with around ten Volunteers in each Section. His appointment to the rank of Company OC was a considerable responsibility for one so young.

Comrade

Easter has an important place in the republican calendar, and in 1942, Belfast republicans were determined to commemorate the 1916 Rising. The problem was that since the 1920s republican parades of any description had been banned. It was decided by the IRA leadership in Belfast that three separate Easter parades would be held and that a number of diversionary operations would be carried out in other areas across Belfast.

Tom, as the OC of C Company, was instructed by his Battalion staff to make the necessary preparations for an operation in the Clonard area. A volley of shots was to be fired over an RUC patrol car that regularly passed by the corner of Clonard Gardens and the Kashmir Road and the Volunteers were to withdraw safely.

In the days preceding the operation, Tom selected and briefed those Volunteers who would take part; eight in total, including Tom himself. The youngest of the group, Margaret Nolan, was just 16 years old, the oldest 21. They met on the day of the operation and around 2.30pm took up their allotted positions.

Shortly after 3pm, an RUC patrol car carrying four constables turned into Clonard Street and headed towards the junction of Clonard gardens and the Kashmir Road. All four [RUC men] were armed with their service revolvers; in addition McMahon carried a pump action shotgun.

As the Ford V Light car passed the junction into Clonard Gardens, Tom and his comrades opened fire. One of the bullets struck the car, smashing a rear window but missing the occupants.

Constable Williamson accelerated into Clonard Gardens, where instead of hastily driving away, Lappin, McMahon and Murphy alighted, drew their weapons and set off at a run back towards Cawnpore Street and the scene of the shooting. The stage was now set for a confrontation that would have far reaching and tragic circumstances.

As the last of the IRA group entered the back kitchen [of number 53], they alerted Tom and the rest of the group to the presence of the RUC on their tail, within seconds all hell broke loose in the tiny back kitchen and scullery. In the controversial statement that Tom later made to the RUC while in hospital, he described what happened:

``I ran into the scullery.There is a little glass enclosure in the yard and from the scullery window I could see a policeman coming into this enclosure with his gun drawn. When he was about three yards from me and beside the kitchen window, I pointed my revolver at his body and fired one shot. He staggered and fired back and I fired four or five more shots at his body.’’

At least two other weapons were fired. According to forensic evidence given at the trial, three of the rounds that struck Murphy were fired from a Webley revolver, the weapon fired by Tom, and two others from the short Webley. Before being fatally wounded in the heart, Murphy fired three rounds from his revolver, whilst the fourth misfired. All three rounds found their mark, striking Tom in his left thigh and once in his left forearm.’’

Prisoner

``Following their arrest, all eight were eventually charged with Murphy’s killing. The two young women were moved to Armagh Jail, while the men were taken to Crumlin Road Jail, except for Tom, who for the moment lay under armed guard in the Royal Victoria Hospital.

Soon Tom was discharged from the jail hospital and joined his comrades on the Wing. Joe Cahill recalls their first meeting. Tom appeared to be `standoffish’’. Sensing that something was wrong he spoke to Tom alone. Upset, Tom explained that he had broken an IRA order and had made and signed a statement to the RUC.

Tom said that while lying injured, he had been told by a doctor and by members of the RUC that he was dying from loss of blood. Then, as now, the IRA ordered its captured volunteers not to cooperate in any way with the enemy authorities. Despite this, Tom decided to make a statement accepting sole responsibility for the killing in the hope that it would save the lives of his comrades.

The trial began on 28 July in number one court, Crumlin Road Courthouse. Seated in the dock were Tom and his five comrades. Weeks before, the charges of murder against their two women comrades had been dropped. The younger of the two, Margaret Nolan, pleaded guilty to a lesser charge and was released with a recorded sentence. Marge Burns was immediately rearrested and interned in Armagh prison.

The defendants were represented by Cecil Lavery, reputed to be one of the best defence barristers in Ireland at the time. On the prosecutors’ bench sat John Clarke McDermott, attorney general for the Six Counties. McDermott was an ex Unionist MP and Stormont minister. Having served as a British officer during the First World War, his unionist sympathies prompted him to join the B Specials in the 1920s.

The trial judge’s unionist credentials were no less impeccable. A committed unionist, Edward Sullivan Murphy was elected unionist MP for Derry City in 1929. A proud and devoted Orangeman, he held the position of deputy Grand Master within the Order for a number of years.’’

Condemned

``The court was silent as the foreman, Thomas Stevenson, rose to read the verdict. He declared, by a unanimous decision, that all six men were guilty of murder but that in the case of Pat Simpson they were recommending mercy because of his youth. On receiving the verdict of the jury, all six young men stood to attention one by one and made a brief statement.

Tom was the last to speak. In a loud and steady voice he declared: ``I am not guilty of murder. I am not afraid to die.’’ The black cap was then placed on Murphy’s head and he passed sentence on the six. Almost immediately an appeal was lodged on behalf of the six and the date of execution was postponed pending its outcome.

Within a few short weeks of the trial, their appeal was heard by Judges Babington, Andrews and Brown. On 21 August the previous verdict of the court was upheld and the new date of execution set for 2 September. Their only hope now lay with the Reprieve Campaign that was being mounted on their behalf outside the prison.

The first act of the campaign was the gathering of a petition calling for clemency. When the petition was handed to the Minister of Home Affairs at Stormont on 21 August, it contained almost a quarter of a million signatures. It was signed by prominent personalities such as Cardinal McRory, three other Catholic bishops, hundreds of Catholic priests and a large number of Protestant clergy, as well as Sean MacBride and a considerable number of MPs and TDs.

Under pressure, de Valera instructed his government officials to intervene on behalf of the six young IRA volunteers. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull took up the case with the British government. The U.S. State Department was urged by Senate and Congressional leaders to intervene. Even the Vatican intervened, pressing the British government to reprieve the men.

On Sunday 30 August the Stormont government issued a statement through the Governor of Northern Ireland. Shortly before the statement was issued, Tom and his comrades were called to a legal visit. When they entered the room they were sombrely greeted by their solicitor D.P. Marrinan. He looked at each of them in turn and finally turned to Tom and said: ``I’ve good news for everyone except Tom.’’

He then told them that all but Tom had been reprieved. There was a stunned silence for a few moments, and then Tom was the first to speak: ``Don’t grieve for me, remember, from day on this is how I wanted it. I wanted to die and I’m happy that you five are going to live.’’

Martyr

``By all accounts, that September morning was shaded by a dark sullen sky overheard. A silence lay across the jail. from the evening before, a large crowd had gathered near the jail and in the hours before the execution many of them knelt quietly in prayer. Throughout Ireland, Catholic churches were filled to capacity for morning mass. In many towns and cities, streets were blocked as hundreds and in some cases thousands stood in silence as a mark of respect.

Tom rose early that morning, dressed, washed and shaved. At around 6.30am he celebrated mass with Fathers Alexis and Oliver and again at 7.15am with Fathers McAllister and McEnaney. Shortly before the stroke of eight, the cell door opened and the two executioners entered, accompanied by the prison governor and a number of prison and city officials.

The main executioner, an Englishman, was Thomas Pierrepoint, assisted by his nephew Albert. Pierrepoint bound Tom’s arms behind his back with a long leather strap. As the buckle of the leather strap was fastened, the two prison guards present moved to either side of a large wooden locker which stood against one of the walls. The locker was lifted to reveal a door - the door to the gallows. Without a falter in his step, Tom calmly walked the last few paces of his life.

A half an hour after the execution, Tom’s five comrades were led from their cells to the prison chapel. The jail was silent. So too was the chapel, except for the sobs of the small group. One of the priests present began to say Mass but broke down weeping. Another priest stood up and continued with the Mass. When the ceremony was over, all present gathered in the sacristy. It was Father Alexis who spoke. ``I met the bravest of the brave this morning.’’

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)