By eirigi

(Irish language version follows)

Over a period of several hundred years the English coloniser managed to almost wipe out the Irish language as the native tongue of the indigenous people and to impose its own language, English, as the new spoken tongue of the country. It is no accident that the English language came to the fore amongst the Irish natives. Imposing English as the first language of Ireland was a pre-meditated project of the English invaders to attempt to condition the people they wished to oppress. The colonisers understood that the Irish language and culture posed a threat to their colonial project. The separate identity of the Irish people comprised that which made them different: their language and culture.

The most powerful attempt to condition the native Irish and to attempt a successful suppression of them as a people was to try and destroy their identity. The most notable aspects of a people’s identity are marked by their unique language and culture. The project of conditioning commenced with the attempt to destroy the Irish language and culture, which was a policy carried out in other countries colonised by England.

A series of events led to the decline of the Irish language. By 1649 the population of Ireland was halved, through the murderous policies of Cromwell and the forced deportation of tens of thousands of Irish. In 1695 the Penal Laws were enforced in which resulted in the proscription of Irish language and culture; the English regarded the Irish as backward and stupid and their language and culture were branded in the same vein.

The foundation of the National Schools in 1831 was a huge blow to the language as Irish was forbidden and those who continued to speak the language were humiliated and punished. Given these policies and the manner in which the Irish had been conditioned to think about their language, it is not surprising that the native Irish people internalised the views of the English, believing their native tongue to be backward and stupid. All education was conducted through English and Irish nationalist politicians at the time abandoned the native language for English. This reinforced the image of the Irish language as representing ignorance and barbarianism. Irish came to be stigmatised and viewed simply as the language of the poor. The Famine of 1845-49 dealt a fatal blow to the Irish language. The massive decline in population during this period, both through starvation and forced emigration resulted in the English language becoming the most common language of the people and as a result the Irish language was on the verge of extinction.

With the founding of Conradh na Gaeilge and the GAA in the late nineteenth century attempts were made to secure the revival of the Irish language and sports and to instil a sense of pride in the Irish for their culture. The leaders of the 1916 Rising recognised that to end imperialism once and for all in Ireland the Irish language and culture would have to be central in the struggle for Irish freedom. Reclaiming their Irish identity would be an important step in the anti-imperialism project and many of those who played a part in the Easter Rising were involved in the revival of the Irish language and in the GAA.

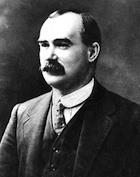

James Connolly was a supporter of the language movement and recognised that capitalism was the main obstacle to the revival of the language which sought to destroy all national identities, cultures or languages:

“The chief enemy of a Celtic revival today is the crushing force of capitalism which irresistibly destroys all national or racial characteristics, and by sheer stress of its economic preponderance reduces a Galway or a Dublin, a Lithuania or a Warsaw to the level of a mere second-hand imitation of Manchester or Glasgow.”

Ireland had now become another version of England where English was spoken and the Irish culture was lost. Connolly spoke of the how the politicians and the Church played their part in the destruction of the Irish language, acquiescing to the ways of the English and encouraging the people to abandon their own identity. He understood that surrendering to English customs resulted in the destruction of language and culture and created in the Irish an inferiority complex: “It was the beginning of the reign of the toady and the crawler, the seoinín and the slave.”

By giving up their language the oppressed had become the slave of the oppressor. Connolly believed in reclaiming the Irish identity for the Irish people, this being the way of throwing off the shackles of oppression. By reclaiming our language and culture we were abandoning the role of the slave and taking back “the distinct character of the Gael”:

“Besides, it is well to remember that nations which submit to conquest or races which abandon their language in favour of that of an oppressor do so, not because of the altruistic motives, or because of a love of brotherhood of man, but from a slavish and cringing spirit. From a spirit which cannot exist side by side with the revolutionary idea.”

The liberation of the Irish people will involve de-colonisation in all forms: a British withdrawal from Ireland, the establishment of a socialist republic and the reclaiming of the culture and language of our country. Because English is the language of economics and the media there is a huge threat posed to all indigenous languages, not only Irish. We can however tackle this threat by looking at the sentiments of those who fought in 1916, which are as relative today as they were then. We must de-colonise our own minds and reclaim our Gaelic heritage of both language and culture.

In the words of James Connolly:

“The success of our cause is certain – sooner or later. But the welcome light of the sun of freedom may, at any moment, flash upon our eyes and with your help we would not fear the storm which may precede the dawn.”

An Conghaileach agus an Ghaeilge

Thar thréimhse cúpla céad bliain is beag nár éirigh le coilínithe Shasana an Ghaeilge a dhíothú mar theanga dhúchais an phobail dhúchasaigh agus a dteanga féin, an Béarla, a fhorchur mar theanga labhartha nua na tíre. Ní taisme é gur tháinig an Béarla chun cinn i measc an bhunaidh. Ba thogra réamhbheartaithe de chuid ionraitheoirí Shasana é an Béarla a fhorchur mar chéad teanga na hÉireann agus iad ag iarraidh an phobal a raibh dúil acu daoirsiú, a riochtú. Thuig na coilínithe go raibh an teanga agus cultúr Gaelach ina mbagairt dá dtogra coilíneach. Chuimsigh féiniúlacht mhuintir na hÉireann é sin a rinne éagsúil iad: a dteanga agus a gcultúr.

Ba é díothú a bhféiniúlachta an iarracht ba thréine leis na Gaeil dhúchasacha a riochtú agus iad a bhrú faoi chois mar phobal. Is iad teanga agus cultúr uathúil na ndaoine na tréithe is suntasaí dá bhféiniúlacht. Thosaigh togra an riochtaithe leis an iarracht teanga agus cultúr na nGael a dhíothú, polasaí a cuireadh i bhfeidhm i dtíortha eile coilínithe ag Sasana.

Bhí meath na Gaeilge ina thoradh ar roinnt imeachtaí. Faoi 1649 laghdaíodh daonra na hÉireann faoina leath, trí pholasaithe dúnmharfacha Chromail agus díbirt d’éigean na ndeiche míle Éireannach. In 1695 cuireadh na Péindlithe i bhfeidhm a raibh toirmeasc na teanga agus an chultúir Ghaelaigh mar thoradh orthu; mheas na Sasanaigh go raibh na hÉireannaigh cúlánta agus dallintinneach agus brandáladh a dteanga agus a gcultúr sa tslí chéanna.

Bhí bunú na Scoileanna Náisiúnta in 1831 ina bhuille mór don teanga mar bhí an Ghaeilge faoi chosc agus náiríodh agus smachtaíodh na daoine a lean ag labhairt na teanga. Níl aon amhras ann, ag féachaint do na polasaithe agus an modh ina riochtaíodh na hÉireannaigh chun smaoineamh ar a dteanga, gur inmheánaigh na hÉireannaigh dhúchasacha dearcthaí na Sasanach, ag créidiúint go raibh a dteanga dhúchasach cúlánta agus bómánta. Seoladh an t-oideachas ar fad trí mheán an Bhéarla agus thug na polaiteoirí náisiúnacha Éireannacha ag an am a ndroim leis an teanga dhúchasach i bhfábhar an Bhéarla. Neartaigh an beart seo an íomhá gharbh agus bharbarach a bhí ag an nGaeilge. Bhí an Ghaeilge tréithrithe agus féachta ar mar theanga na mbocht. Bhí an Gorta Mór 1845-49 ina bhuille tubaisteach don Ghaeilge. Bhí meath ollmhór ar an daonra i rith na tréimhse seo, tríd ocras agus eisimirce éigeantach, agus mar thoradh air bhí an Béarla mar an teanga ba choitianta ag na daoine agus mar thoradh ar an nGaeilge a bheith ag bordáil ar dhíobhadh.

Le bunadh Chonradh na Gaeilge agus Chumann Lúthchleas Gael ag deireadh na naoú haoise déag rinneadh iarrachtaí athbheochan na Gaeilge agus spóirt na hÉireann a áirithiú agus chun mórtas cine a chur ina luí sna hÉireannaigh dá gcultúr. D’aithin ceannairí Éirí Amach 1916 chun deireadh a chur le himpiriúlachas go deo in Éirinn go mbeadh ar an gcultúr a bheith lárnach sa streachailt do shaoirse na hÉireann. Bheadh athshealbhú a bhféiniúlachta mar chéim thábhachtach sa togra frithimpiriúlachais agus bhí an-chuid de na daoine a ghlac páirt in Éirí Amach 1916 bainteach le hathbheochan na Gaeilge agus leis an CLG.

Ba thacadóir é Séamus Ó Conghaile de chuid ghluaiseacht na teanga agus d’aithin sé gurb é an caipitleachas an príomhchonstaic a bhí ann d’athbheochan na Gaeilge a bhí ag iarraidh féiniúlachtaí náisiúnta, cultúir, nó teangacha go léir a scriosadh:

“The chief enemy of a Celtic revival today is the crushing force of capitalism which irresistibly destroys all national or racial characteristics, and by sheer stress of its economic preponderance reduces a Galway or a Dublin, a Lithuania or a Warsaw to the level of a mere second-hand imitation of Manchester or Glasgow.”

Bhí Éire anois ina leagan eile de Shasana ina labhraíodh Béarla agus ina raibh cultúr na hÉireann caillte. Labhair Ó Conghaile faoin mbealach a ghlac na polaiteoirí agus an Eaglais a bpáirt féin i scriosadh na Gaeilge, ag géilleadh do bhealaí na Sasanach agus ag spreagadh na ndaoine chun a bhféiniúlacht féin a thréigeadh. Thuig sé gurb é toradh ar ghéilleadh do chleachtaí na Sasanach ná scriosadh teanga agus cultúir agus gur chruthaigh sé coimpléasc ísleachta: “It was the beginning of the reign of the toady and the crawler, the seoinín and the slave.”

Tríd a dteanga a thabhairt suas bhí an duine i ndaoirse anois mar sclábhaí an tíoránaigh. Chreid Ó Conghaile in athshealbhú féiniúlachta na hÉireann do mhuintir na hÉireann, ’sé seo an tslí chun geimhle na daoirse a chaitheamh uathu. Tríd ár dteanga agus ár gcultúr a athshealbhú bhíomar ag tabhairt droim le ról an sclábhaí agus ag tógaint ar ais “the distinct character of the Gael”:

“Besides, it is well to remember that nations which submit to conquest or races which abandon their language in favour of that of an oppressor do so, not because of the altruistic motives, or because of a love of brotherhood of man, but from a slavish and cringing spirit. From a spirit which cannot exist side by side with the revolutionary idea.”

Beidh díchóilíniú i ngach cruth ag teastáil do shaoirse mhuintir na hÉireann: aistarraingt na Breataine ó Éirinn, bunú poblachta sóisialaí agus athshealbhú an chultúir agus teanga ár dtíre. Toisc go bhfuil an Béarla mar theanga na heacnamaíochta agus na meán tá baol ollmhór ann do na teangacha dúchasacha go léir, ní amháin don Ghaeilge. Tá muid ábalta dul i ngleic leis an mbaol seo áfach tríd féachaint ar mhaoithneachais iad siúd a throid i 1916, atá chomh coibhneasta inniu is a bhí ansin. Caithfidh muid ár meonta féin a dhíchóiliniú agus ár n-oidhreacht féin de theanga agus cultúr a athshealbhú.

I mbriathra an Chonghailigh:

“The success of our cause is certain – sooner or later. But the welcome light of the sun of freedom may, at any moment, flash upon our eyes and with your help we would not fear the storm which may precede the dawn.”

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/rn.gif)

![[Irish Republican News]](https://republican-news.org/graphics/title_gifs/harp.gif)